Frittura Piccante di Gurda Kaleji: Delizia Classica di Frattaglie

(Spicy Gurda Kaleji Fry: Classic Offal Delight)

(0 Recensioni)0

789

luglio 28, 2025

Segnala un problema

Ingredienti

-

250 grams Reni di agnello

(Cleaned, trimmed of membranes, sliced thin)

-

250 grams Fegato di agnello

(Sliced thin, any veins removed)

-

1 large Cipolla rossa

(Tagliato finemente)

-

1 medium Pomodoro

(Diced small)

-

2 pieces Peperoncini verdi

(Finely chopped; adjust to heat preference)

-

2 tbsp Pasta di zenzero e aglio

(Macinato fresco preferito)

-

2 tsp Polvere di coriandolo

-

1 tsp Polvere di cumino

-

1 tsp Polvere di Peperoncino Rosso

(Use Kashmiri chili for color, regular for more heat)

-

1 tsp Polvere di Curcuma

-

1 tsp Garam masala

-

1 tsp Sale

(A piacere)

-

2 tbsp Foglie di coriandolo fresco

(Tritato, per guarnire)

-

4 pieces Spicchi di limone

(To garnish and squeeze over before serving)

-

3 tbsp Olio (senape o girasole)

-

1 tsp Foglie di fieno greco (kasuri methi)

(Optional, dried)

(Cleaned, trimmed of membranes, sliced thin)

(Sliced thin, any veins removed)

(Tagliato finemente)

(Diced small)

(Finely chopped; adjust to heat preference)

(Macinato fresco preferito)

(Use Kashmiri chili for color, regular for more heat)

(A piacere)

(Tritato, per guarnire)

(To garnish and squeeze over before serving)

(Optional, dried)

Nutrizione

- Porzioni: 4

- Dimensione Porzione: 1 piatto (250g)

- Calories: 320 kcal

- Carbohydrates: 9 g

- Protein: 29 g

- Fat: 18 g

- Fiber: 2.5 g

- Sugar: 3 g

- Sodium: 700 mg

- Cholesterol: 340 mg

- Calcium: 55 mg

- Iron: 8.6 mg

Istruzioni

-

1 - Clean and prepare offal:

Carefully clean the kidneys and liver under cold water. Remove any membrane or connective tissue. Slice thin and soak kidneys in water with a dash of lemon juice for 10 minutes to mellow the flavor.

-

2 - Prepare Aromatics:

Finely chop onion, tomato, and green chilies. Mince coriander leaves for garnish. Have ginger-garlic paste ready.

-

3 - Heat spices and temper aromatics:

Heat oil in a wide pan on medium-high heat. Add onions and sauté until soft and golden brown (about 3-4 minutes).

-

4 - Sauté kidney and liver:

Add ginger-garlic paste and green chilies. Stir and cook for 45 seconds. Add sliced kidney and liver and fry for about 2 minutes, tossing to coat in aromatics.

-

5 - Add ground spices:

Lower heat to medium. Sprinkle in coriander, cumin, red chili, turmeric, and a pinch of salt. Cook for 1 minute until fragrant.

-

6 - Tomato and gentle simmer:

Add tomatoes and cook, stirring, until they soften and blend in. The mixture should look slightly saucy but thick.

-

7 - Finish and Garnish:

Sprinkle in garam masala and kasuri methi (if using), then stir well. Fry until any liquid evaporates and it’s oil-speckled. Taste, adjust salt or chili.

-

8 - Serve Hot:

Plate the hot Gurda Kaleji Fry, garnish with coriander and lemon wedges. Serve immediately with naan or hot rotis.

Carefully clean the kidneys and liver under cold water. Remove any membrane or connective tissue. Slice thin and soak kidneys in water with a dash of lemon juice for 10 minutes to mellow the flavor.

Finely chop onion, tomato, and green chilies. Mince coriander leaves for garnish. Have ginger-garlic paste ready.

Heat oil in a wide pan on medium-high heat. Add onions and sauté until soft and golden brown (about 3-4 minutes).

Add ginger-garlic paste and green chilies. Stir and cook for 45 seconds. Add sliced kidney and liver and fry for about 2 minutes, tossing to coat in aromatics.

Lower heat to medium. Sprinkle in coriander, cumin, red chili, turmeric, and a pinch of salt. Cook for 1 minute until fragrant.

Add tomatoes and cook, stirring, until they soften and blend in. The mixture should look slightly saucy but thick.

Sprinkle in garam masala and kasuri methi (if using), then stir well. Fry until any liquid evaporates and it’s oil-speckled. Taste, adjust salt or chili.

Plate the hot Gurda Kaleji Fry, garnish with coriander and lemon wedges. Serve immediately with naan or hot rotis.

Ulteriori informazioni su: Frittura Piccante di Gurda Kaleji: Delizia Classica di Frattaglie

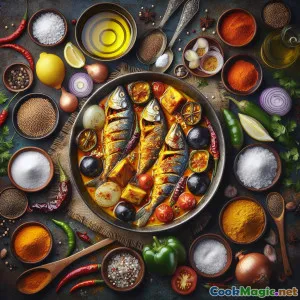

Gurda Kaleji Fry: The Bold Flavors of Indian Offal Cooking

Gurda Kaleji Fry is a dish that stands proudly among the treasures of North Indian and Mughlai culinary heritage. While India is wonderfully known for its array of vegetarian and chicken curries, few travelers realize the depth of offal cookery threaded through street stalls and old households, particularly in regions that value slow-cooked comfort with strong, aromatic flavors.

Kaleji (liver) and gurda (kidney) are prized throughout India, especially during Eid festivities or on days when a robust meal is desired. The high-protein offal, revered for its intensity, is most beloved when quickly fried in a thick masala, trading off lemon’s brightness and spices’ perfume for the melt-in-mouth texture of the organ meat. At its best, Gurda Kaleji Fry tastes distinctly earthy, spicy, and satisfying, with the vivid warmth of green chilies, the warmth of garam masala, and sheen from its finishing oil—all designed to be scooped up with naan, roomali roti, or even toasted bread.

History & Cultural Significance

What makes Gurda Kaleji Fry important is its rootedness in Indian street food—often sold outside mosques in the Old City during morning hours along with breads and black tea. Travelers to Lucknow, Delhi or Hyderabad would routinely see vendors serving greasy, spicy heaps in tin plates to working men. For many, this protein-rich breakfast was an affordable, sustaining treat, using parts of the lamb that are rich in nutrients yet quick to cook.

Its roots dig deeper into Mughal kitchens—the ruling classes would favor kaleji, gurda, brain, all fried briefly for pre-dawn meals. Over time, all communities have developed their signature seasoning blend, with South India introducing more curry leaves and coconut while the North emphasizes dried fenugreek and fresh coriander. This dish continues today both at roadside dhabas and at home, particularly among families honoring old culinary practices.

Unique Aspects & Chef’s Tips

The unique pleasure of this fry is in taste and texture. Powers of flavor extraction reign here: soaking kidneys in lemony water removes much bitterness, while frying offal briefly at high heat keeps it tender. Go overboard on cooking time, and liver will stiffen—a common misstep; aim to add the offal only after your spices and onions are about done, then finish swiftly. Thick slices also help retain moistness—a key to a luscious communal pot anyone will crowd around.

Many add a last flourish of sliced ginger or a splash of cream, but for authenticity I prefer just Kasuri methi (dried fenugreek leaves) and lemon at the end: fresh punch, herbal restoration! Adjust chili wisely; this dish should offer a gentle, pleasing heat rather than a searing burn.

Paired with buttery paratha or soft, hot roti, this is a showstopper centerpiece for an Indo-Pakistani festive family dinner, but it just as easily elevates a ‘street food’ themed party or Sunday breakfast.

Serving & Personal Thoughts

I first sampled Gurda Kaleji Fry in old Mumbai, watching a street chef expertly tossing slivers of crimson organ meats and chilies in a modest iron wok. The result, layered onto hot bread alongside slices of raw onion and a puckering wedge of lime, was unforgettably rich and dynamic. The medley of texture—kidney’s slight chew, liver’s delicate creaminess, onion’s bite, the lemon’s aroma—proves that boldness in cuisine can often come from simplicity, trust in fresh ingredients and classic technique.

Gurda Kaleji Fry isn’t just a dish; it’s an embrace of tradition, thrift, and the skill that underlies even India’s most modest dining scenes. There’s community in every plate: share, talk, mop up every spiced smear with naan, and taste history direct.

Tips & Notes

- Use only the finest, freshest offal for the best results! Old liver or kidney may contribute bitterness or graininess.

- Always fry in a thick, heavy-bottomed pan—nonstick or carbon steel both work.

- For lighter flavor, use more tomato and consider brief simmering covered after frying spices.

- The dish is deeply rich on its own, but is best enjoyed freshly made and piping hot, as reheating can impact texture.

Bring Gurda Kaleji Fry to your table for a taste of Indian roots cuisine—always vibrant, packed with history, and utterly unforgettable.