The History of Indigenous American Corn Dishes

13 min read Explore the rich cultural roots and traditional recipes of indigenous American corn dishes, highlighting their significance in centuries-old culinary practices. August 23, 2025 03:05

The History of Indigenous American Corn Dishes

Imagine walking into a bustling marketplace in the heart of Central America, where the air is thick with the aroma of roasted maize, tangy lime, and smoky chili. Brightly colored tortillas shimmer under the sunlight, and families gather around open fires, crafting dishes rooted in centuries of tradition. This vivid tapestry of flavors and stories is woven from the very fabric of indigenous American cuisine—specifically, the profound and multifaceted world of corn.

Corn, known as maize to many, is far more than just a staple crop; it is a symbol of life, identity, spirituality, and resilience for countless indigenous communities across North, Central, and South America. Its origins date back thousands of years, and the dishes born from this sacred grain have evolved into exquisite culinary expressions that continue to thrive today. Let us embark on an immersive journey through the history of indigenous American corn dishes, exploring their cultural significance, traditional preparation methods, and enduring legacy.

The Origins of Maize in Indigenous Cultures

Maize's journey begins in ancient Mesoamerica, where archaeological evidence pinpoints its domestication approximately 9,000 years ago in the Balsas River Valley of present-day Mexico. Early farmers, observing the drought-resistant and highly nutritious qualities of wild grasses, selectively cultivated and refined their crops over generations, gradually transforming wild teosinte—a wild grass with tough kernels—into the plump, golden ears we cherish today.

For indigenous peoples like the Maya, Aztecs, and Toltecs, maize was much more than sustenance; it was a divine gift. Mythologies often recount maize as a gift from the gods, embodying the cycle of life, death, and renewal. The ancient Maya, for example, crafted elaborate codices depicting maize gods, emphasizing the crop's sacred status.

The cultivation of maize became intertwined with spiritual practices. Fields were seen as sacred spaces, often dedicated to specific deities, and planting rituals accompanied planting seasons. Corn wasn’t just food—it was a living entity, a carrier of cultural memory.

Traditional Methods of Cooking Corn: From Tamales to Nixtamalization

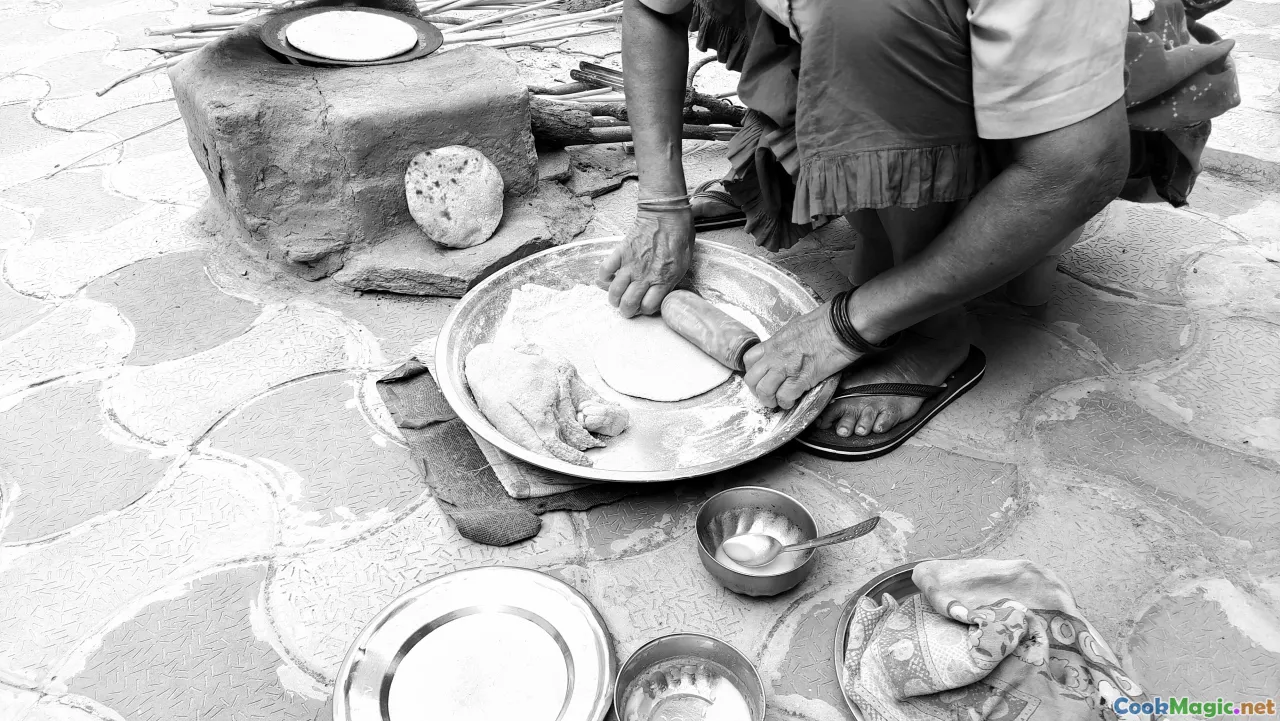

One of the most remarkable aspects of indigenous corn cuisine is the method of nixtamalization, a process still revered today for its ability to unlock the grain's nutritional and flavorful potential. In this process, dried maize kernels are soaked and boiled in an alkaline solution—traditionally, lime (calcium hydroxide)—then washed and ground into masa, a fresh dough.

This technique dates back over 3,000 years and revolutionized how indigenous peoples prepared corn. Nixtamalization improves the bioavailability of niacin, reduces mycotoxins, and imparts a distinctive aroma, flavor, and soft, pliable texture to the dough.

Once prepared, masa becomes the base for a plethora of beloved dishes. For example:

- Tortillas: Thin, round discs that serve as the groundwork for numerous meals—from simple accompaniments to elaborate tacos.

- Tamales: Wrapping seasoned masa around fillings like meat, vegetables, or chilies, then steaming them in corn husks or banana leaves—these are hearty, portable, and packed with flavor.

- Pupusas: Originating from Central America, these thick corn tortillas stuffed with cheese, beans, or pork showcase the versatility of masa.

In regions like Mexico’s Oaxaca, preparing fresh masa daily is a ritual, connecting generations through the tactile and sensory experience of pounding, kneading, and shaping.

Corn in Cultural Rituals and Festivals

Corn’s role transcends everyday sustenance, embedding itself deeply into the spiritual and cultural fabric of indigenous communities. Festivals celebrating maize are common across the continent. For instance, in Mexico, the Guelaguetza festival in Oaxaca features elaborate dance, music, and offerings to maize deities, emphasizing gratitude and reverence.

In the Andean highlands, Fiesta del Maíz celebrates the harvest with traditional dances, where ritualized burning of cobs symbolizes renewal and abundance. These festivities serve as vital opportunities to pass down stories, songs, and cooking techniques, ensuring that the sacred relationship with maize remains alive.

Native American tribes such as the Cherokee, Navajo, and Hopi incorporate maize into spiritual rites, planting ceremonies, and communal feasts. The Green Corn Ceremony, observed in many tribes, marks not only the renewal of the maize crop but also the renewal of community bonds.

Signature Indigenous Corn Dishes Across the Americas

As a culinary historian, one loves to explore the myriad ways indigenous communities have transformed maize into dishes that tantalize the senses and connect past with present. Here are some iconic regional staples:

Pozole (Mexico)

A hearty, hominy-based stew infused with Ancho chilies, garlic, and herbs. Traditionally served during celebrations, each bowl is generously garnished with shredded lettuce, radishes, lime, and oregano—sensory layers culminating in bold, invigorating flavors.

Atol and Champurrado (Mexico and Central America)

Warm, velvety beverages made from masa and spices like cinnamon and vanilla. They evoke comforting, earthy aromas—perfect for cold mornings or festive winter mornings.

Ears of Grilled Corn (Corn on the Cob)

Simply seasoned with lime juice, chili powder, and cotija cheese, this street food embodies the rustic, smoky charm of indigenous culinary traditions, especially in the Southwest United States and Mexico.

Tamalitos and Hallacas (Central and South America)

In Central America, hallacas—similar to tamales—are wrapped in banana leaves and filled with a complex mix of meats, olives, and raisins, showcasing a blend of indigenous and colonial influences.

Chicha de Maíz (Andean regions)

A traditional fermented beverage with a sweet, sour aroma, made by fermenting maize, often flavored with fruits or spices. Its cultural significance as a communal drink during festivals and rites underscores maize's sacred role.

Colonial Encounters and Transformation of Corn Dishes

With the arrival of Europeans, indigenous maize cuisine experienced both upheaval and adaptation. Spanish colonizers introduced new ingredients like lard, sugar, and dairy, which slowly merged with traditional recipes.

For example, tortilla-like flourproducts, such as churros or certain bread styles, began to incorporate wheat, yet the spirit of maize persisted robustly, especially in rural communities. The fusion created innovative dishes likemoganadasin Central America andpan de muerto with maize-based dough during colonial religious festivals.

The colonial period also led to the widespread dissemination of maize dishes beyond native borders, with variations appearing in Caribbean islands, southern U.S. states, and even as far as the Philippines, where maize was integrated into local cuisine.

However, amidst these changes, indigenous practices—such as the ceremonial planting of maize and preservation of heirloom varieties—persisted in many communities, safeguarding the cultural significance of maize.

Modern Revivals and Indigenous Pride in Corn Cuisine

Today, there is a renewed appreciation and respect for indigenous corn dishes, driven by culinary collectives, food sovereignty movements, and a desire to reclaim cultural identity. Chefs and home cooks alike seek out heirloom maize varieties—such as blue, red, or striped corns—and revive age-old recipes.

Farmers markets across the United States and Mexico showcase authentic nixtamalized corn and traditional products. Chefs like Ricardo Muñoz Zurita in Mexico and Sean Sherman, the “Rebel Chef,” in the U.S., champion indigenous ingredients and techniques, bridging cultural heritage with contemporary cuisine.

In festivals globally, you see corn increasingly celebrated not only as a nutritious grain but as a symbol of resilience, communal memory, and cultural pride. Indigenous communities organize cooking workshops, storytelling sessions, and harvest festivals to transmit their ancestral knowledge.

Personal Reflections and the Future of Indigenous Corn Dishes

The story of indigenous American corn dishes is ultimately one of stewardship and reverence. Growing up in a community where maize recipes were passed from elders, I learned that each tortilla, each tamale, carries a story—a chronicle of history, environment, and spirituality.

In our rapidly globalizing culinary landscape, preserving these traditions requires conscious effort. Whether through supporting small-scale indigenous farmers, learning traditional preparation methods, or simply savoring authentic dishes, each bite honors generations of toil, ingenuity, and spiritual connection.

Looking ahead, the future of indigenous corn dishes lies in their power to educate, inspire, and unify. As more chefs and home cooks embrace these vibrant flavors, they weave a richer, more inclusive tapestry of American cuisine—one that recognizes the profound roots from which it grew.

In celebrating maize, we celebrate the indomitable spirit of indigenous communities—the real heart of American culinary history—whose enduring legacy continues to grow, diversify, and flourish in every kernel cracked and every dish shared.