The Art of Xiao Long Bao Folding

42 min read Master the iconic 18-pleat fold of Shanghai soup dumplings with dough, filling, and pleating tips rooted in tradition for delicate, juicy xiao long bao perfection. October 09, 2025 03:08

The Art of Xiao Long Bao Folding

The first thing you learn about xiao long bao isn’t their name. It’s the hush that falls over a table when the bamboo steamer lid lifts and the room breathes ginger and pork and hot, sweet steam. Your fingers tremble at the thought of a rupture. Your lips hover over a porcelain spoon as if it were a tea ceremony chalice. Xiao long bao is a test of patience, a measure of temperature—and, in the hands of a skilled cook, a lesson in geometry. Each pleat is a quiet promise that the skin will hold, the stock will stay, and that the very first bite will be a held breath turned into a sigh.

This is an essay about that promise—the folds that make the soup sing. If you’ve ever watched a Shanghai master gather a paper-thin disc of dough, coaxing it into a tiny lantern full of molten broth, you’ve seen that the art of xiao long bao folding is as much choreographed as it is cooked. Today, I’ll show you how to fold what you taste and why those folds matter.

The First Time I Burned My Tongue in Shanghai

I was twenty-two when I stood in the shadow of the Yuyuan Garden pavilions, watching the queue snake out past Nanxiang Mantou Dian, that old temple of dough that helped carry xiao long bao from neighborhood snack to global icon. The rain made the tiles shine, and every few minutes a vendor somewhere shouted for vinegar and ginger while the clack of bamboo lids rose like applause.

When my steamer arrived—three tiers, paper as lining, no cabbage, the way the old-timers like it—I committed a beginner’s mistake. I lifted a dumpling by its pleated topknot, too eager to make a trophy of it, and the skin tore. A ribbon of broth spilled, slick as silk, onto my spoon and then my shirt. I stared at the empty pouch, embarrassed and newly reverent. The vendor, an auntie with a grease-satin scarf tied around her hair in the familiar Shanghai style, shook her head, picked up another dumpling, and cradled it under its belly, as if cupping a bird. She tipped it into my spoon, whispered, Wait, and mimed a small bite—just the corner, a breath of cool—then sip. That ritual has guided me ever since.

But before that lesson at the table, there is the lesson at the bench. It begins in the dough and ends in the fold.

A Short History of Pleats

Xiao long bao belongs to the Jiangnan region—the humid, river-laced south of the lower Yangtze—where people nurture a cuisine that sits somewhere between Suzhou’s sweetness and Shanghai’s cosmopolitan polish. The name itself simply means small basket buns, though they are closer to dumplings than bread. The version we know developed in the late 19th century in Nanxiang, a town now swallowed by Shanghai’s sprawl. Local lore credits a vendor who added a jellied stock to enrich his mantou; when that stock melted in the steamer, he had an accidental marvel.

What makes xiao long bao singular is not only the soup inside, but the disciplined frill at the top—the folds that seal, anchor, and shape how you eat them. In Beijing, jiaozi are closed with a simple crimp; in Canton, har gow wears a handful of crisp ridges. Xiao long bao, by contrast, are a rosary of pleats all pointing in one direction, converging in a neat crown. The count varies by hand and house, but 18 pleats became famous as a benchmark, a tidy integer you’ll see on posters at Din Tai Fung and whispered like a prayer by culinary students. Others do 21 or 24. What matters is not blindly hitting a number but creating a seal that is even, beautiful, and thin enough to disappear in the mouth.

The fold is cultural shorthand. At dinner tables from Shanghai to Singapore, parents challenge teenagers to spot an apprentice’s dumplings—clumsy, thick-knotted—among a tray of masters’ work. The best xiao long bao carry a soft translucence; hold one against a window in late afternoon and you can almost make out the shadows of the aspic within, like amber lit from behind.

The Anatomy of a Perfect Wrapper

You can’t fold what you can’t stretch. The wrapper is your canvas, and its behavior under your fingertips dictates how delicate your pleats can be.

Flour: Use a medium-protein flour—something in the 10–11% range. In the United States, a blend of all-purpose with a touch (10–15%) of cake flour yields a tender but resilient dough. In China, many shops use specialized dumpling flours with a slightly lower ash content for a clean white finish.

Water: A hybrid dough gives you the best of both worlds: tenderness from scalded flour, strength from cold water. My ratio:

- 100% flour

- 20–30% of that flour scalded with boiling water (tangmian method)

- Total hydration 40–48%, adjusted for humidity

Method:

- Take 30% of your flour and pour in an equal weight of boiling water. Stir with chopsticks until it forms little pearls that look like wet sand. This scalded portion gelatinizes starch, making the dough more extensible and tender.

- Add the remaining flour and enough cold water to bring the total hydration to 40–48%. Start low if your air is humid and go higher in dry climates.

- Knead until smooth, 8–10 minutes, rest 20–30 minutes under a damp cloth, then knead briefly again. Resting is non-negotiable; it allows gluten to relax, which is what lets you roll edges thin without recoil.

Target thickness: Roll wrappers to roughly 1.2 mm in the center and 0.8 mm at the edge. That gradient matters. The center needs backbone to hold soup; the edge must gather into pleats without becoming a gummy knot. Pros achieve this by rolling with a short dowel pin and rotating the dough with the other hand, thinning the circumference while leaving the center slightly thicker.

Diameter: 7.5–9 cm. Larger wrappers are easier for learners but risk thicker pleat bases; smaller ones require nimble fingers.

Texture: When right, the dough feels cool and slightly tacky without sticking. Press a finger in; it should spring back slowly, like a pillow you want to nap on. Too tight, and your pleats will tear. Too slack, and they won’t hold shape.

Aspic: The Secret River Inside the Dumpling

You can fold the world’s prettiest pleats and still fail if there is no river to release when you bite. Xiao long bao is a delivery system for soup, and that soup begins with an aspic that melts into a glossy broth in the steamer.

Stock bones and aromatics matter. In Shanghai, cooks favor a mix of pork skin, pork bones, and sometimes chicken backs for clarity. A sliver of Jinhua ham perfumes the pot without bullying it. Ginger and scallions are standard; a splash of Shaoxing wine brightens. Keep the boil civilized—bare tremors, not a rolling rage—so your stock stays clear.

Aspic method:

- Simmer pork skin (scraped and rinsed) with bones, chicken backs, scallion whites, ginger coins, and a small piece of Jinhua ham for 4–6 hours. Skim diligently.

- Strain. You are looking for a clean, lightly amber stock. Reduce gently until it coats the back of a spoon.

- Season with light soy for salt, a whisper of sugar for balance, Shaoxing for aroma. Remember that gelatin dulls perceptions of salt; season to the edge of what tastes right when hot.

- Chill until set. The set should wobble, not sit like a rubber eraser. If your collagen isn’t enough, bloom a little gelatin to assist, but know that a pure skin-and-bone set has a superior mouthfeel.

Filling:

- Minced pork shoulder (70–80% lean) is classic; its fat melts into the soup. Some kitchens blend a small portion of hand-chopped meat for texture.

- Mix meat with minced ginger, scallions, white pepper, a touch of sugar, light soy, Shaoxing wine, and sesame oil. Stir in one direction until sticky—it should cling to the bowl, developing a slight bounce known in Chinese kitchens as shangjin.

- Fold in diced aspic gently, keeping everything cold. Warmth is the enemy; a warm filling will leak long before it meets steam.

When right, the filling smells faintly of ginger and wine, with no aggressive garlic to cloud the pork’s sweetness. Hold a cube of aspic between your fingers; it should smudge slightly as your skin warms it—reminding you to work quickly.

Mise en Place for a Folding Session

Folding is not a heroic act. It’s a system.

Set your station like a conductor’s podium:

- Dough balls under a damp cloth on your left.

- Rolling pin—a short, tapered dowel about 25–30 cm long—within reach.

- Bench flour in a small bowl; I prefer wheat starch or cornstarch for dusting because it doesn’t toughen the dough as much as raw flour.

- Wrapper stack covered with a slightly damp towel. Never let the edges dry.

- Filling and aspic in a chilled bowl, nested in another bowl with ice if your room is warm.

- A small scale if you’re chasing consistency: 8–10 g wrappers, 14–18 g filling per piece for home practice.

- Bamboo steamer lined with parchment punched with holes, or a bed of Napa cabbage leaves to prevent sticking and to scent the steam.

Before you begin, wash and dry your hands thoroughly. A thin film of flour on the right fingertips helps grip; clean hands resist sticking better than oily ones. Remove rings. Tie back hair. Think of it as a tea ceremony. You are trying to create consistency by ritual.

The 18-Fold Method, Step by Step

Folding a xiao long bao is choreography more than brute force. Here’s a home-friendly workflow that mirrors what I learned in a Shanghai dumpling shop, condensed into a steady rhythm.

- Place a wrapper in your left palm, slightly cupped. The center should sit over the fleshy pad near your thumb, not dangling from your fingertips.

- Spoon the filling: a neat mound in the center. No heaping. If you can see the filling through the wrapper edge, you’ve overdone it.

- Start your first pleat near the 12 o’clock position. Pinch a small segment of edge between your right thumb and index finger and fold it over about 5–7 mm.

- Rotate the dumpling slightly with your left hand—your left palm becomes a lazy Susan—while your right hand gathers a new segment of edge and lays it over the previous pleat. Always in the same direction.

- Continue pleating, keeping each pleat equal in width. Your right hand is the zipper; your left hand feeds the fabric. Aim for 16–20 pleats evenly spaced. Count aloud if it helps. The count keeps you honest.

- As you near full closure, you’ll see a small opening. Gently push any trapped air out by pressing the filling down with your thumb. Air pockets are bubbles waiting to explode in the steamer.

- Finish with a final pleat that covers the gap. Pinch the crown firmly to seal. Some cooks twist the topknot slightly, but don’t overdo it; a tight twist forms a dense dough ball that won’t cook through at the same rate.

- Set the dumpling onto your parchment-lined steamer with a confident downward motion. Don’t slide; friction can tear the base.

Your first batch will look like cousins, not twins. That’s good. Consistency grows from repetition. The goal is even tension, not identical faces.

Hand Mechanics: Left-Hand Turntable, Right-Hand Zipper

I once spent an hour with a master named Wang in a modest shop off Yunnan Road, a place more famous for its scallion pancakes than for dumplings. He let me fold beside him, an act of grace I remember every time I touch dough. He corrected not my speed, but my posture.

Left hand: a cradle and a turntable. The angle of your palm controls the curve of the wrapper around the filling. If your hand is flat, the wrapper slides; if too cupped, pleats crowd. Keep the palm gently concave, and rotate the dumpling a half-centimeter at a time with micro-movements of the thumb and middle finger. Think of tuning a radio dial.

Right hand: the zipper. Thumb and index finger do the pinching; the middle finger supports from behind, nudging the dough forward. Your pinches should be decisive—hesitation leaves half-moon bites that can leak.

Consistency: Each pleat should overlap the previous by a third to a half. Imagine roofing tiles. Overlap creates the seal; alignment creates the pattern. If you find your pleats wandering, try lightly scoring four compass points on the wrapper edge with the corner of your fingernail. Use them as waypoints.

Pressure: There is a moment when the dough thins whisper-slight between your fingernails. That’s the edge you want. Too hard and you tear; too soft and you stack bulky pleats. Practice pinching a scrap of rolled dough until you can feel the membrane tension.

Training Drills for Your Hands

Like calligraphy, folding improves when you decouple movement from outcome. Here are a few drills I give culinary students and new line cooks.

- The empty pleat: Roll 30 small wrappers. Fold them empty, focusing on pleat width and overlap. You’ll learn how much tension you can create without the filling complicating your grip.

- Coin challenge: Place a coin (a dime is ideal) in the center of a wrapper and pleat to enclose it. The goal is to minimize the topknot bulk while fully encasing the coin. Disassemble after to check your overlap.

- Clay class: Use a small piece of air-dry clay or playdough to mimic filling. Clay doesn’t chill your fingers but holds shape, letting you practice hand positioning endlessly.

- Metronome work: Set a metronome to 60 bpm and aim for one pleat every two beats. Rhythm helps avoid clumsy hesitations.

- Mirror check: Place a small mirror at your station to watch your right-hand pinch from the side. Seeing your finger and thumb alignment is strangely corrective.

After a week of 20 minutes a day, your fingers will find a groove. It’s a muscle memory you can feel even when you’re washing dishes.

Common Mistakes and How to Fix Them

- Tears at the pleat base: Your wrapper edge was too thin or dry. Increase resting time before rolling, or dust less aggressively while rolling edges. Work under a slightly more humid towel.

- Thick, gummy topknot: You’re stacking pleats without thinning them. Pinch harder and overlap more. Try trimming 1–2 mm from the wrapper edge before you begin to reduce bulk.

- Leaks in the steamer: Air pockets expand and rupture seals. Before closing, press the filling down gently with your thumb to release air. Also, ensure your aspic isn’t sweating into the wrapper as you work—chill the filling.

- Flat bottoms that stick and rupture: Line your steamer with parchment punched with holes or use Napa cabbage leaves. Lightly brush the parchment with sesame oil if your dough tends to stick.

- Wrappers snapping back while rolling: The dough needs more rest or more scalded-flour percentage. Let the dough relax or adjust the hot-cold water ratio next time.

- Soupless bites: Your aspic ratio is too low or has melted before steaming. Keep the filling cold; don’t let finished dumplings sit at room temperature for long. Steam within 10–15 minutes of folding or refrigerate briefly.

Steam and Serve: Protecting Your Pleats

Steaming is the final guardian of your work. Treat each dumpling like glass.

- Water: Bring to a vigorous boil before you set the steamer over it. Once the bamboo hits the pot, lower to a steady strong simmer. A violent boil can knock dumplings into each other; too low and the skins turn pasty before the filling heats.

- Time: For standard home-size xiao long bao, 6–8 minutes. You’re aiming for a faintly translucent skin and a slightly domed shape. If your pleats collapse, you’ve gone too long or overfilled.

- Spacing: Leave a thumb-width between dumplings. They expand. Crowding leads to kissing pleats and tears.

- Lids: Do not lift in the first 4 minutes. Temptation is strong. Resist.

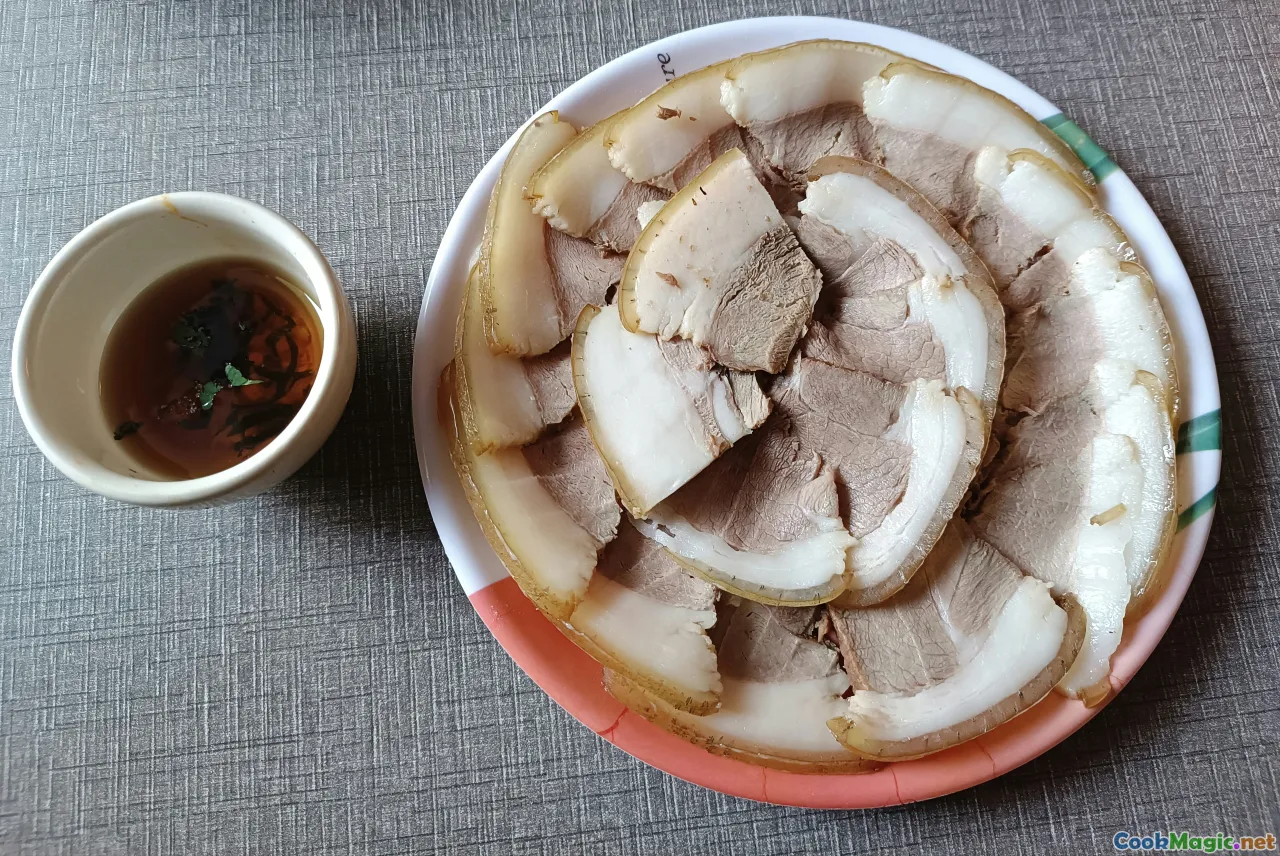

- Service ritual: Present with a shallow dish of black vinegar scented with batons of fresh ginger. I like a ratio of 3 parts Chinkiang vinegar to 1 part light soy, plus a dot of sugar to round the edge.

Eating is a craft, too. Transfer a dumpling to a porcelain spoon, cradle it against the spoon’s curve, nip a small hole near the pleats, and sip. The broth should be glossy, clean, pork-sweet, with a gingery inhale and the balsamic fragrance of vinegar trailing behind. Only then should you dip the meat and wrapper into the ginger vinegar and take the rest in one or two bites. Revel in the tug of the skin. It should yield, not dissolve.

Regional Variations and Respectful Deviations

Xiao long bao has cousins that deserve respect and help you understand what makes it unique.

- Tangbao: In Yangzhou and Nanjing, tangbao balloons to grapefruit size and arrives with a straw. The skin is thicker, the straw is play, and the broth is more assertively savory. Folding is simplified—fewer pleats, a robust seal, and a ceremonial straw puncture.

- Shengjian bao: Pan-fried in Shanghai, with a leavened dough and sesame-seed bottoms crisped in oil. The pleats sit downward here, cooking into a lacy skirt. A different sport altogether, but the notion of managing internal pressure applies.

- Suzhou-style xiao long: Often a shade sweeter, reflecting Su cuisine’s palate. Sometimes a pork-and-crab roe filling appears in season, with roe contributing both aroma and a briny, sunset-orange sheen to the soup.

- Taipei’s Din Tai Fung style: Standardized 18 pleats, a slightly firmer skin, and a flavor profile that leans clean and elegant. Watch their open kitchens for lessons in speed—fingers flying in unison like a troupe.

Comparing these styles makes clear that folding is not only aesthetics—it reflects the cooking method and desired bite. The thin pleats of Shanghai xiao long bao ask for gentle steam; the sturdy ridges of shengjian are designed for a sizzling pan.

Places to Taste and Learn

If you’re learning to fold, eat widely. Your hands listen better when your mouth knows what it’s chasing.

- Nanxiang Mantou Dian, Shanghai: The grand old name. Go early to avoid the tourist crush. Order both the classic pork and the crab roe when in season. Watch the bench if you can—older workers set the rhythm.

- Jia Jia Tang Bao, Shanghai: A humbler shop with a cult following. The skins are delicate; the soup hits with ginger brightness. Their wrappers taught me the value of that center-thick, edge-thin gradient.

- Din Tai Fung, Taipei and worldwide: Standard-setting consistency. If you want to understand the modern franchise approach to craft, watch how they portion filling, how the scales sit on the bench, how a team handles dough like an assembly of watchmakers.

- Crystal Jade La Mian Xiao Long Bao, Singapore: Try the crab roe versions; note the way the roe’s fat interacts with the skin.

- Joe’s Shanghai, New York: A gateway for many Americans to the soup dumpling. The skins are robust, the broth generous. A lesson in how a heartier wrap changes the eating cadence.

Take notes as if you were in a wine tasting: skin thickness, pleat definition, broth clarity, seasoning balance, vinegar pairing. It’s not nerdy; it’s how craft improves.

A Note on Flour, Water, and Climate

Dough is weather. On a humid July day in Shanghai, with air heavy as a steamed bun, you’ll need less water and more bench flour. In Denver, high altitude and dry air turn your dough brittle; a touch more hot water improves extensibility. Keep a log.

Guidelines:

- If the dough fights you while rolling edges thin, add a teaspoon of oil per 300 g of flour next time or increase the scalded portion by 5%.

- If wrappers dry out while you fold, increase towel humidity or work in smaller batches.

- If pleats fuse in the steamer and lose definition, your hydration is too high or your steam is too aggressive. Adjust the boil or reduce hydration by 2–3%.

Temperature matters for the filling too. People often forget that gelatin melts at body temperature. If your kitchen is warm, the aspic will weep. Keep the bowl nested in ice, and rotate two small bowls rather than one large one. After 15 minutes on the bench, return the filling to the fridge and switch.

Service Ritual: Vinegar, Ginger, and Patience

I have seen diners drown a dumpling in vinegar as if it were a salad. Resist. Xiao long bao wants a companion, not a cloak. Chinkiang vinegar’s malt depth and gentle acidity cut the pork’s richness; ginger threads add fragrance and a peppery lift.

Prep the ginger by slicing paper-thin and then cutting into fine batons. Soak them briefly in cool water to crisp and tame any harshness. Let guests add ginger to vinegar to their taste.

Most important: patience. You waited hours for stock to become aspic, minutes for dough to rest, and seconds for steam to rise. Give the dumpling another 15–20 seconds on the spoon after you lift it before you nip. The skin tightens, the soup settles, and your palate thanks you.

For the Vegetable Lover: Plant-Based Xiao Long Bao

The architecture of folding invites variation. For a plant-based version, respect the structure and the ritual.

Aspic without bones:

- Build a stock from roasted mushrooms, dried shiitake, kombu, ginger, scallion whites, and a few toasted white peppercorns. Reduce for depth.

- For gel, agar-agar gives a bouncy set; konnyaku jelly yields a different chew. A blend of agar and a touch of kappa carrageenan creates a silkier gel closer to animal collagen. Dial it to a wobble, not a hard block.

Filling options:

- Minced king oyster mushroom and water chestnut for crunch; pressed tofu for protein; a bit of sesame oil and a smidge of fermented bean curd for umami.

- Some chefs add a tiny spoon of truffle paste. If you do, use restraint; let the mushroom stock carry the melody.

Wrappers are the same. The folding is the same. The joy is the same—hot broth; a scent of forest; a curl of steam escaping the pleats like a secret.

The Emotional Geometry of 18 Pleats

If you cook for a living, your hands collect small biographies—burns from the salamander, a callus where the knife rests, a nick you remember because the night was busy and you ignored it. Folding xiao long bao writes a different story in your fingers. It is quiet, repetitive, slightly obsessive. You mark time in pleats.

When I apprenticed with Wang, he told me his father folded dumplings while listening to the evening news. His father’s father folded while listening to the river beyond their window. When we fold, we are not reproducing a dish, we are participating in a domestic choreography that extends back through kitchens we’ll never see. Eighteen pleats is a number, yes. But it is also a meditation: start, overlap, continue, close.

A Working Recipe You Can Trust

For the reader who wants numbers to anchor the poetry, here is a compact, reliable formula tailored for a home kitchen. It’s not the only way, but it will hold you.

Wrappers (30–36 pieces):

- 300 g all-purpose flour (10–11% protein)

- 40 g cake flour

- 95 g boiling water (for scalding ~30% of the flour)

- 95–115 g cold water, as needed

- 2 g salt (optional)

Method: Scald 100 g of the flour with the boiling water, stir to pebbles, cool slightly. Add remaining flour(s) and salt, then drizzle in cold water while mixing. Knead 8 minutes, rest 30, knead 2 minutes, rest another 20. Portion into 12–14 g balls, keep covered. Roll to 8–9 cm, edges thinner than center.

Pork filling and aspic:

- 350 g pork shoulder, finely minced

- 1 tbsp light soy sauce

- 1 tbsp Shaoxing wine

- 1 tsp sugar

- 1/2 tsp fine salt (adjust later)

- 1/4 tsp white pepper

- 1 tsp sesame oil

- 1 tbsp finely minced ginger

- 2 tbsp finely minced scallion whites

- 250 g chilled aspic, cut into 5–6 mm cubes

Method: Mix seasonings into pork in one direction until sticky. Fold in aspic gently. Taste test by microwaving a teaspoon of filling for 10–15 seconds; adjust salt.

Folding: 14–18 g filling per wrapper. Pleat as described. Steam 7–8 minutes over lively simmer.

Serving: Chinkiang vinegar with ginger batons. Smile.

Small Details the Pros Don’t Skip

- Wrapper aging: After rolling a batch, let the discs rest for 5 minutes under a cloth before filling. The gluten relaxes and the edge becomes more cooperative.

- Fill-then-fold pace: Work in sets of six. Fill all six quickly, then fold in sequence. This gives the wrappers a minute to accept the filling’s moisture but not enough to soak through.

- Silent check: Pick up a finished dumpling and gently shake next to your ear. You should feel the filling shift slightly. If it feels like a solid ball, your wrapper is too thick or your filling too dry.

- Vinegar warm-up: Warm the vinegar in a small bowl by setting it on the steamer lid for a minute. Aromatics bloom in warmth.

- Clean steam: Refresh the steaming water every few rounds. Starchy drips cloud steam and can scent later dumplings with a stale note.

Understanding Failure Without Fear

On a winter night in a cramped apartment in Taipei, I once served a platter of xiao long bao that looked perfect and ate like sadness. The skins were too thick, the broth under-seasoned, the pleats ostentatious without purpose. My guests were kind, but I knew. The next day, I walked to a commerce-district Din Tai Fung and ordered one basket fore and one basket aft of lunch rush, so I could sit and compare. The difference was restraint. Their pleats were not merely pretty; they were proportionate. Their skin didn’t announce itself but yielded in the mouth and vanished like a well-timed joke. I went home and cut 1 g from each wrapper portion, 2 g from each filling portion, and everything fell into place.

Failure is information. Fold a dozen that leak and ask: where did air hide, where did the dough dry, where did my fingers rush? The answer is always in your hands, and that’s good news.

Why Folding Matters More Than a Perfect Recipe

Recipes are maps. Folding is walking the path. Precision in ingredients ensures you’re in the right province, but your pleats determine whether the dumpling sings or merely hums. Folding controls thickness, which controls heat transfer, which controls when the aspic melts and how the soup behaves under pressure. Folding controls the seal, which decides whether you have soup or apology. Folding shapes the crown, which changes how you bite—and thus how you taste.

When you pleat well, the dumpling inflates slightly like a lantern in steam, its topknot just substantial enough to grab without tearing, its belly taut. The first bite draws a ribbon of stock that coats your tongue, corners your palate with pork sweetness, and leaves behind clean wheat and ginger. You don’t notice the fold count; you notice the moment when sound drops out of the room.

On nights when my shoulders ache and my knuckles protest, I remind myself that these folds are small acts of hospitality turned into form. My teachers in Shanghai and Taipei taught me that love is folding the last dumpling with the same care as the first. The art is not a flourish. It is a promise you keep, one pleat at a time.

And so, when the bamboo lid lifts at your table and the vinegar winks in its dish, breathe. Lift a dumpling by its belly, not its crown. Nip, sip, smile. Somewhere in those pleats, there are hands you’ve never met, an old garden in the rain, a whisper of Shaoxing in the steam. May your folds be even, your broth clear, and your patience rewarded.