Southeast Asian Street Food You Can Make at Home

42 min read Discover authentic, weeknight-friendly recipes for Southeast Asia’s iconic street foods—banh mi, satay, pad thai, and more—plus pantry tips, shortcuts, and cultural notes for cooking at home. October 08, 2025 06:08

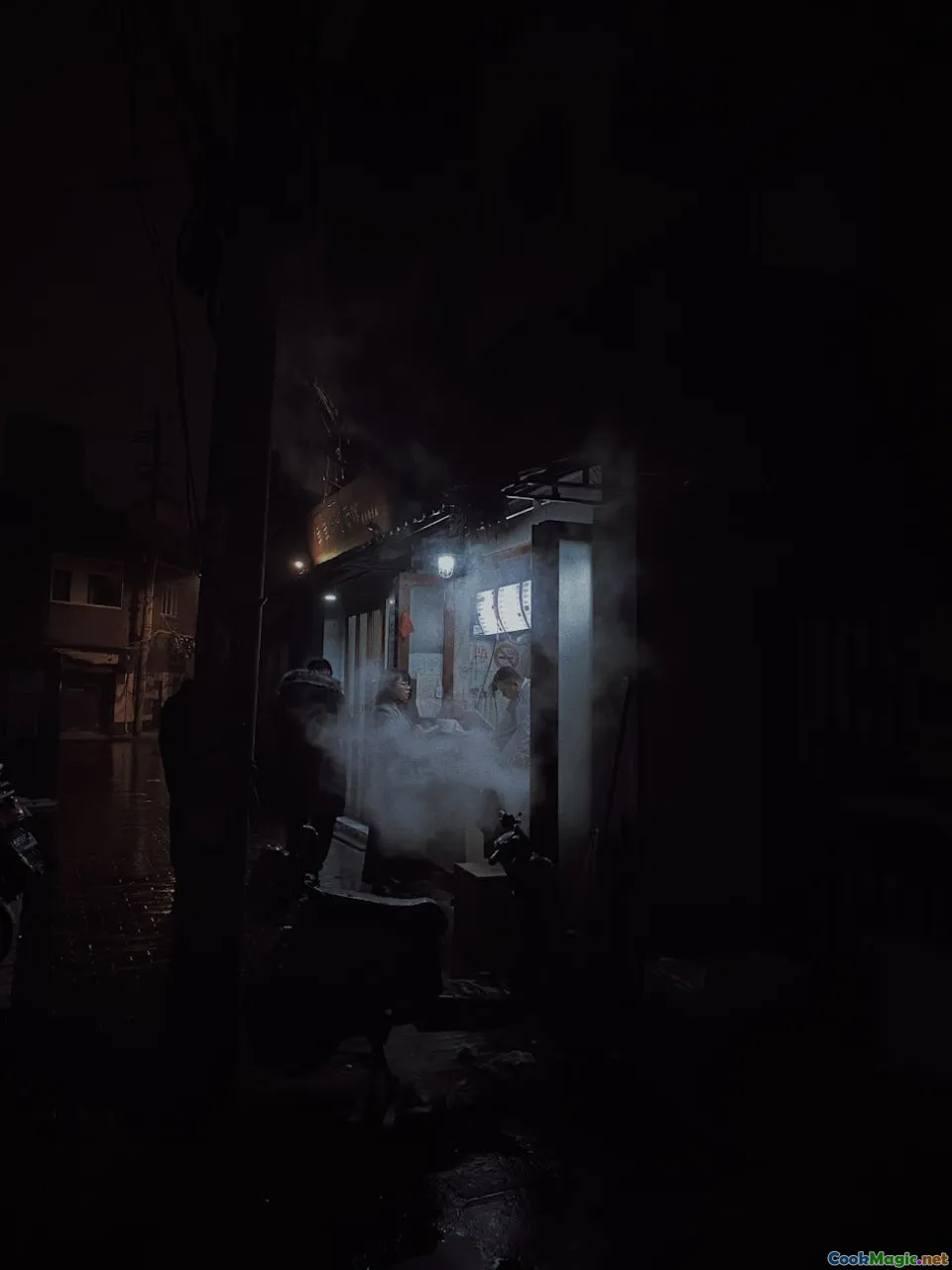

The first time a Bangkok alley taught me how to eat, it was past midnight and the air tasted like smoke, sugar, and engine oil. A wok spat a comet tail of flame while a grandmother in a tie-dye apron fanned skewers of pork until the fat wept and the glaze turned lacquered and sticky. Somewhere, a mortar was cracking green papaya into ribbons of thunder. That alley was a classroom and a kind of church, and I have been trying to bring it home ever since.

Street food is more than grit and fire. It is choreography: the small pan that always knows where to land, the hand that can feel the right heat without a thermometer, the rhythm of sugar, salt, and acid keeping time. The good news for a home cook? You have every tool you need: a pan that gets hot, a sharp knife, and the hunger to learn what your nose already understands.

The street-food mindset at home

There is a reason Southeast Asian street food tastes like speed and memory. Dishes are built fast but with ingredients that have been building their voices for days: fish sauce fermenting for months, coconut milk coaxed from old groves, chili pastes pounded until the room’s windows fog. At home, you can mimic that snap of freshness and the depth of a slow chorus by staging your prep and respecting the balance.

Think like a vendor:

- Cook in batches and stage components. Street food is modular; sauces are made ahead, herbs are washed and spun dry, proteins sit marinating while rice cooks in the background. Do the same.

- Heat is a language. You do not need a restaurant wok burner. Preheat your heaviest pan until it is almost shimmering, then move fast. For grills, preheat until you cannot hold your hand above the grate for more than two seconds.

- Edges matter. Lime squeezed at the table, herbs added with your fingers, fried shallots raining down like brittle confetti. These finishing touches are the soul of the stall.

The mindset is also social. A hawker stall is a conversation between cook and queue. At home, that translates to dishes that finish at the table: herbs to pick, sauces to spoon, rice to share. The kitchen becomes the street, in the best way.

Build your Southeast Asian street pantry

Every stall has a crate of essentials, the bottles smudged with fingerprints and the labels softened by heat. Stock these and half your work is done.

- Fish sauce: The heartbeat. Look for brands from Vietnam or Thailand with short ingredient lists. It should smell like low tide and taste like ocean thunder. Start with a few drops and build.

- Soy sauce family: Light soy for salt and brightness, a splash of dark soy for color and depth. Sweet soy (kecap manis) is Indonesian caramel in a bottle, molasses-thick and perfumed with star anise.

- Lemongrass, galangal, and kaffir lime leaves: The holy trio of Thai and Indonesian broths and curries. Freeze with a smile; the aromas survive.

- Tamarind: Buy paste or concentrate. It should taste like sour apricot and sunlight. Great for pad Thai, asam laksa, and dipping sauces.

- Palm sugar: Comes as cakes or granules. It does not shout like white sugar; it hums—caramel, smoke, and a plum-like finish.

- Shrimp paste: Funk with a capital F. Toast it in foil over a burner or in the oven to tame it. Sambals live and die by it.

- Rice and noodles: Jasmine rice for everyday, sticky rice for grilling nights and mango desserts. Rice noodles in various widths; egg noodles for char kway teow.

- Coconut milk: Save the thick cream for finishing. Shake cans first, and taste—brands vary from fresh-tasting to oily.

- Herbs and crunchy things: Thai basil with its peppered perfume, cilantro roots if you can find them, mint for cooling, sawtooth herb for Vietnam’s whisper of pine. Fried shallots, roasted peanuts, crisped garlic.

Substitutions to keep you cooking: if tamarind is elusive, a mixture of lime juice and a touch of brown sugar works in a pinch. No palm sugar? Mix white sugar with a pinch of molasses. For lemongrass, the zest of a lemon and a woody sprig of rosemary can gesture toward its citrus-wood personality.

Fire and smoke: Satay two ways

On Jalan Alor in Kuala Lumpur, a satay vendor flips skewers like an oud player plucking a storm, each turn mapping sugar to char. At home, you can edge close to that coal-kissed magic with a backyard grill or even a broiler, and you can choose your allegiances: Malaysian-style marinade with turmeric and lemongrass, or a more Indonesian profile heavy on coriander and sweet soy.

Base marinade (makes enough for 2 pounds of protein):

- 2 stalks lemongrass, tender inner parts only, finely chopped

- 4 cloves garlic

- 1 thumb of ginger or galangal

- 2 teaspoons ground coriander

- 1 teaspoon ground cumin

- 1 tablespoon turmeric powder

- 2 tablespoons palm sugar (or brown sugar)

- 2 tablespoons fish sauce

- 1 tablespoon light soy sauce

- 2 tablespoons neutral oil

- Optional: 2 tablespoons kecap manis for Indonesian sweetness

Directions:

- Pound aromatics in a mortar or blitz in a processor to a paste. Smell it: you should feel a lemony punch up front, warm roots in the middle, spice drifting after.

- Toss with chicken thigh strips, beef, or extra firm tofu. Thread onto soaked bamboo skewers. Marinate 2 hours or overnight.

- Grill over medium-high heat, rotating frequently, basting with leftover marinade thinned with oil. If broiling, place skewers on a rack set over a sheet pan and cook on the top rack, turning once, until caramelized.

Peanut sauce that hugs:

- 1 cup roasted peanuts, blitzed to a rough paste

- 2 cloves garlic, minced

- 1 small shallot, minced

- 1 tablespoon red curry paste or sambal oelek

- 1 tablespoon palm sugar

- 2 tablespoons tamarind water

- 1 cup coconut milk

- Fish sauce to taste

Simmer the aromatics in a splash of oil until fragrant, stir in peanuts, coconut milk, sugar, and tamarind. Adjust with fish sauce and water until it falls from the spoon like velvet. Serve warm with satay, cucumber slices, and compressed rice cubes if you have them.

Two ways, two moods: The Malaysian skewer reads turmeric-bright and slightly bitter in the most grown-up way; the Indonesian style leans sweet and smoky, the char like toffee. Both need that blunt cucumber crunch on the side and the kiss of lime at the end.

The honk of lime and fish sauce: Sauces to keep close

You do not cook street food so much as assemble it around sauces that know your secrets. A quick roster can lift grilled meats, noodles, salads, and even fried eggs into something that tastes like a motorbike hum.

Vietnamese nuoc cham (the universal dip):

- 3 tablespoons fish sauce

- 3 tablespoons lime juice

- 3 tablespoons water

- 1.5 tablespoons sugar

- 1 clove garlic, minced

- 1 small bird’s eye chili, sliced

- Optional: a few shreds of carrot for color

Stir the sugar into warm water to dissolve, then add the rest. The balance should hit salt first, then acid, then sweet. Adjust until your mouth waters more than once.

Thai nam jim jaew (smoky-sour for grilled meats):

- 2 tablespoons fish sauce

- 2 tablespoons lime juice

- 1 tablespoon palm sugar

- 1 tablespoon toasted rice powder

- 1 teaspoon chili flakes

- 1 tablespoon chopped cilantro and scallion

Toast raw sticky rice in a dry pan until nut-brown, then grind. Mix with everything else. It should be tart and perfumed, with tiny grains crunching like sand on a beach.

Sambal matah from Bali (uncooked, raw heat):

- 4 shallots, thinly sliced

- 3 bird’s eye chilies, thinly sliced

- 1 stalk lemongrass, tender inner part, minced

- 1 kaffir lime leaf, slivered (optional but sublime)

- 2 tablespoons coconut oil, warmed until liquid

- Salt and a squeeze of lime

Toss and let sit ten minutes. The oil blooms the aromas. Spoon over grilled fish, scrambled eggs, fried rice. It is a bright razor.

Vietnam at your countertop: Banh xeo and bun cha night

Vietnam invites you to play with textures: crisp meeting silk, fresh herbs puckering against warm smoke. Two home-friendly recipes deliver that alleyway joy.

Banh xeo, the thunder crepe:

The name means sizzling cake and the sound is your guide. The batter should whisper into hot oil and set at the edges first, lacy and golden.

Batter for 4 crepes:

- 1 cup rice flour

- 1 tablespoon cornstarch

- 1 cup coconut milk

- 3/4 cup water

- 1/4 teaspoon turmeric

- Pinch of salt

- Optional: chopped scallions

Fillings: thinly sliced pork belly or mushrooms, shrimp, bean sprouts, sliced onion.

- Whisk batter and let rest 20 minutes. Heat a nonstick skillet with a slick of oil until shimmering. Scatter a few slices of pork and onion, sear briefly, add a few shrimp.

- Pour in a thin layer of batter, tilting to coat. The edges should bubble like lace. Lower heat slightly, add bean sprouts on one side, and cover for 1 minute.

- Uncover and let the crepe crisp until the color deepens. Fold and slide out. Serve with a mountain of herbs (mint, Thai basil, cilantro), lettuce leaves, and nuoc cham for dipping. Wrap, dunk, grin.

Bun cha, Hanoi’s lunch of smoke:

- Ground pork patties with grated shallot, fish sauce, sugar, black pepper, and chopped dill or cilantro. Form small, slightly flat patties.

- Grill over high heat or broil until char-kissed.

- Serve with warm rice vermicelli, a bowl of diluted nuoc cham with shredded carrot, fresh herbs, and crisp lettuce. Dunk the patty in the sauce, toss with noodles, add herbs until the bowl looks like a garden after rain.

If you remember the Obama table at Bun Cha Huong Lien in Hanoi, think of that balanced chaos: char, cool greens, bright sauce, soft noodles. It is a full conversation in a bowl.

Thailand in a skillet: Pad Thai versus pad see ew

There are noodles you dance to and noodles you hum. Pad Thai is the dancer—tamarind-tart, peanut-crumbed, chive-bright. Pad see ew is the hum—smoky with soy, tenderness wrapped around charred greens. Both are doable at home if you think more about sequencing than flair.

Pad Thai essentials for two servings:

- Sauce: 2 tablespoons tamarind concentrate, 2 tablespoons fish sauce, 2 tablespoons palm sugar. Adjust to a bright, sweet-sour-salty triangle.

- 6 ounces soaked rice noodles (medium width), still with a little bite

- 2 cloves garlic, minced; 1 small shallot, minced

- 6 shrimp or a handful of pressed tofu strips

- 2 eggs

- 1 cup bean sprouts; handful garlic chives or scallions

- Toppings: roasted peanuts, lime, chili flakes, pickled radish if you have it

Method:

- Preheat the pan until a drop of water skitters into beads. Add oil, fry garlic and shallot briefly; they should sigh, not brown deeply.

- Add protein, stir until nearly cooked. Push aside, crack eggs, scramble softly.

- Add noodles and sauce; toss with tongs until the noodles turn glossy and inhale the sauce. If dry, splash a tablespoon of water. Finish with sprouts and chives off heat.

- Plate and crown with peanuts and lime. The noodles should be supple, edges picked up with tang.

Pad see ew tips:

- Wide fresh rice noodles are best; loosen with a bit of oil.

- Sauce: 1 tablespoon light soy, 1 tablespoon dark soy, 1 teaspoon sugar, 1 teaspoon fish sauce.

- Heat the pan fiercely. Char Chinese broccoli or a similar green. Push aside, add noodles, sauce, and let one side kiss the pan undisturbed to develop that smoky signature.

- Stir just enough; too much and you lose the magic of seared edges.

Comparison in a breath: pad Thai tilts tart-sweet and agile, pad see ew leans umami with ballast. Both are quick, both reward heat discipline, both beg for a small bowl of sliced chili in vinegar at the table.

Breakfast to midnight: Singapore and Malaysia hawker staples

Hawker centers in Singapore and kopitiam culture in Malaysia teach restraint. Nothing is wasted, nothing is extra. The chicken rice that lines Maxwell Food Centre tastes pure because it is an essay on chicken, rice, and stock.

Hainanese-style chicken rice at home, simplified:

- Poach a whole chicken or bone-in thighs with ginger, scallion, and a few grains of white pepper. Reduce to a bare tremble; do not boil. When just cooked, plunge into ice water to set the skin into satin.

- Skim the stock. In a saucepan, sauté minced garlic and ginger in chicken fat or oil, add rinsed jasmine rice, stir until glossy, then cook in the chicken broth with a pinch of salt. A knotted pandan leaf perfumes everything if you have it.

- Sauces: a quick chili sauce (blend fresh chilies with garlic, ginger, lime, sugar, fish sauce), dark soy for gloss, and grated ginger in oil with salt. Slice chicken, pour a few spoonfuls of hot stock over, serve with the rice that smells like comfort.

Char kway teow for the determined:

- Ingredients: fresh wide rice noodles, Chinese chives, bean sprouts, a handful of blood cockles if you are bold, Chinese sausage slivers, egg, and chili paste.

- Sauce: 1 tablespoon light soy, 1 tablespoon dark soy, 1 teaspoon fish sauce, 1 teaspoon sugar, a dab of sambal.

- Heat a small batch at a time in a carbon steel pan smoking hot. Render a bit of pork fat or use oil, sear sausage and garlic, add noodles and sauce, toss quickly, push aside and scramble an egg, then fold in sprouts and chives. Let parts of the noodle sit still to pick up char. The taste should be smoke, sweet soy, and the faint metallic kiss of cockles if used.

Nasi lemak, Malaysia’s coconut lullaby:

- Rice: simmer jasmine rice with coconut milk, water, pandan, and a pinch of salt until the kitchen smells like a tropical afternoon.

- Sambal tumis: fry blended chilies, onion, garlic, and shrimp paste until the oil separates and turns brick-red; sweeten with palm sugar, sour with tamarind.

- Serve with crispy fried anchovies, roasted peanuts, cucumber slices, and a jammy egg. Optional fried chicken or rendang if ambition stirs. The plate is a still life of crunch, heat, and creamy rice.

Indonesia after rain: Nasi goreng, sate, and the language of sambal

Jakarta’s street carts come with their own music: a wooden block knocked with a dowel to call you closer. The fried rice that follows is smoky-sweet, a midnight fix that tastes like the day collected and distilled.

Nasi goreng at home:

- Cold rice from yesterday. This is a rule as old as the cart.

- Aromatics: shallot, garlic, chili, a spoon of shrimp paste if you dare, bloomed in oil until your kitchen smells like thunderclouds and flowers.

- Sauce: kecap manis and a splash of light soy for salt.

- Protein and veg as desired: leftover chicken, shrimp, cabbage shreds.

- Stir-fry until the rice grains separate and gloss, then crown with a fried egg whose edges lace and whose yolk runs. Serve with crunchy krupuk crackers and sliced cucumber.

Sambal is the archipelago’s chorus. Keep a versatile sambal oelek on hand (chilies, vinegar, salt), then riff with shrimp paste for sambal terasi or add tomatoes for sambal tomat. Taste your chilies before you commit; heat varies like weather. For a smoky note, char the chilies and tomatoes over a gas flame first.

If satay remains in your mind, skewers of chicken in Java are brushed repeatedly with a glaze of kecap manis and lime, then fanned over a tiny charcoal stove until the sugars catch and bead. In Yogyakarta’s angkringan, little parcels of rice called nasi kucing come with a smear of sambal and a sliver of fish, proof that few ingredients can still hit a drum.

The crunch stand: Filipino street snacks you can actually pull off

Manila after school smells like frying oil and vinegar. Orange-glazed quail eggs called kwek-kwek pile up like marbles, and skewers of grilled chicken intestines called isaw hiss over coals, brushed with banana ketchup and calamansi.

At home, borrow the spirit safely and happily:

Kwek-kwek, bright and brittle:

- Boil quail eggs, peel, dry thoroughly.

- Batter: 1/2 cup flour, 1/2 cup cornstarch, 1 teaspoon baking powder, salt, water to make a thick, pourable batter, and a few drops of annatto or paprika for color.

- Dip eggs, deep-fry at 350 F until blistered and crisp. Serve with spiced vinegar (vinegar, garlic, chili, a whisper of sugar) or a sweet-sour brown sauce.

Isaw mood, thigh version:

- Marinate chicken thigh strips with soy sauce, banana ketchup, calamansi or lime, brown sugar, garlic, and black pepper. Skewer and grill hot, basting until glossy.

Turon, the merienda that smiles while you fry:

- Wrap ripe saba banana or plantain sticks with jackfruit slivers in lumpia wrappers, sprinkle with sugar, roll, and fry in shallow oil until the sugar caramelizes and the wrapper shatters. Snacking becomes a verb.

Halo-halo for dessert:

- Layer crushed ice with sweetened beans, nata de coco, palm seeds, leche flan cubes, purple yam jam, and evaporated milk. Stir until it looks like after-school chaos. Eat until the spoon clinks glass.

Bowls of dawn: Mohinga, kuy teav, and nom banh chok

Morning in Yangon tastes like mohinga—catfish broth thickened with toasted rice, perfumed with lemongrass and banana stem. Breakfast noodles across the region begin the day with lean strength and a tangle of herbs.

Mohinga simplified at home:

- Base: sauté onion, garlic, ginger, and lemongrass until sticky and aromatic. Add turmeric, paprika, and a spoon of shrimp paste.

- Liquids: fish or chicken stock, plus a small can of mackerel or flaked cooked fish if catfish is beyond reach.

- Thickener: toasted rice powder whisked in until the broth drapes a spoon.

- Finish with fish sauce and lime, then serve over rice vermicelli with crisp fritters, cilantro, and chili flakes. The flavor is river-deep, brightened by citrus.

Kuy teav, the Cambodian noodle soup:

- A clear pork or chicken broth, laced with charred onion and star anise.

- Rice noodles, topped with ground pork cooked with garlic, a few slices of fish cake or shrimp if you like.

- Garnish with scallion, cilantro, fried garlic, and a squeeze of lime. On the side, chili paste and a dab of hoisin if you must.

Nom banh chok, the green sunrise:

- Fermented fish-based green curry poured over rice noodles, with shredded cucumber, banana blossom, and herbs. At home, make a gentle cheat by blending green curry paste with coconut milk, fish sauce, and a touch of anchovy for depth, then pour over cold noodles. It is a meadow in a bowl.

Fresh and fermented: Salads that slap awake

Street salads are not diet food; they are percussion. Som tam in Thailand makes your lips buzz; laab in Laos and Isan is lime, mint, and roasted rice pounded into meat confetti; laphet thoke in Myanmar folds the funk of fermented tea leaves into crunch.

Som tam tips:

- Use a mortar and pestle if possible. Pound garlic and chilies first, add palm sugar, then long beans and cherry tomatoes, bruising to release juice. Shred green papaya or crunchy cucumber and carrots, toss with fish sauce and lime. The goal is bruise, not mash.

- Taste the rhythm: sour should lead, salt and sweet chase, heat keeps the beat.

Laab at home:

- Brown ground pork or chicken lightly, then toss warm with lime juice, fish sauce, toasted rice powder, chili flakes, sliced shallot, mint, and cilantro.

- Serve in lettuce cups with cucumber and sticky rice. The perfume of mint and the grit of rice powder will take you to a roadside table with plastic stools.

Laphet thoke workaround:

- If fermented tea leaves are hard to find, make a leafy cousin: strong-brewed green tea leaves soaked, squeezed dry, then tossed with garlic, chili, lime, fish sauce, crispy chickpeas or peanuts, sesame seeds, tomato, and cabbage. It is not canonical, but it is honest and delicious.

Sweet endings and iced things: Cendol, mango sticky rice, and more

Street sweets soothe the mouth after chilies. They also whisper of pandan and palm sugar, flavors that taste like a breeze through shade trees.

Mango sticky rice:

- Steam soaked glutinous rice until tender. Warm coconut milk with sugar and a pinch of salt; pour most over the hot rice and let it drink. The grains will shine like pearls.

- Serve with ripe mango cheeks and a drizzle of the remaining coconut milk. Top with sesame seeds or fried mung beans for crunch.

Cendol, a bowl of jade:

-

Make cendol jelly by mixing rice flour and mung bean starch with pandan juice or extract and water; cook until thick, then press through a cendol mold or a colander into ice water to set into wriggly green worms.

-

Assemble with shaved ice, coconut milk, and gula melaka syrup (palm sugar melted with water and a pinch of salt). The flavor is heat’s antidote.

Thai roti with condensed milk:

- Fry a stretchy dough on a griddle until crisp and blistered, fold with butter, drizzle with condensed milk and sugar. Shortcut: use store-bought paratha, fry and finish. It is carnival in a square.

Vietnamese coffee ice cream hack:

- Whip cream, fold in sweetened condensed milk and strong Vietnamese coffee, freeze in a loaf pan until scoopable. Serve with a sprinkle of crushed peanuts and a pinch of salt.

Sourcing, substitutions, and gear that help more than gadgets

A good Asian grocery is a map. Walk the aisles with curiosity and restraint. Pick a few new things each trip and give them jobs at home: a jar of fermented bean curd for stir-fries; dried shrimp for sambal; pandan paste for rice. If you do not have a specialty store nearby, reputable online shops can get you kaffir lime leaves, Vietnamese rice paper, and Filipino banana ketchup without a scavenger hunt.

Substitution sanity:

- Tamarind: if you only have concentrate, dilute and strain before adding to sauces. If none, mix lime juice with a bit of brown sugar. The note will be different but serviceable.

- Fish sauce: brands range from elegant to brash. Taste straight from the bottle to calibrate. If the funk is too sharp, a splash of water and a pinch of sugar can soften it in sauces.

- Shrimp paste: toast wrapped in foil on a burner or in a toaster oven. If the smell worries the household, use a small amount of Thai fish sauce to evoke some depth.

- Herbs: cannot find Thai basil? Use a mix of regular basil and a few mint leaves for that anisey cool.

Gear that matters:

- Carbon steel wok or a heavy 12-inch skillet: both can sear. Season a carbon steel wok well and heat until it smokes before oiling for stir-fries.

- Grill or broiler: skewers and char are happier with live flame, but a broiler, a preheated cast-iron grill pan, and a patient cook can build color too.

- Rice cooker: not glamorous, but perfect rice is a canvas. Many models have a setting for sticky rice; if not, steam soaked sticky rice in a bamboo basket or a mesh sieve lined with cheesecloth.

- Mortar and pestle: pounding unlocks aromas differently than blades. If using a processor, pulse and scrape often, and let pastes sit a few minutes to open up.

- Ventilation and smell diplomacy: cook shrimp paste and high-heat stir-fries when windows are open, a candle is lit, and the neighbors are charmed with a plate of dumplings later.

A night market at home: menus and timelines

Street food is a parade. The trick at home is to prep like a vendor and finish like a magician.

Sample menu for six:

- Skewers: chicken satay with peanut sauce and cucumber pickles

- Noodles: pad see ew or char kway teow, cooked in two small batches

- Fresh roll: banh xeo or crispy rice paper omelets with herbs

- Salad: som tam or laab with lettuce cups

- Rice: jasmine or nasi lemak coconut rice if leaning Malaysian

- Dips: nuoc cham, nam jim jaew, sambal matah

- Sweet: mango sticky rice or turon served with coffee

Make-ahead game plan:

Two days before:

- Grocery and herb wash. Spin-dry and store herbs wrapped in paper towels inside a container.

- Fry a jar of shallots and garlic chips for finishing. Store airtight.

One day before:

- Marinate satay and skewer. Refrigerate.

- Mix sauces: nuoc cham, nam jim jaew. Store cold.

- Soak sticky rice if making mango sticky rice.

- Toast rice for laab and grind.

Morning of:

- Make peanut sauce, sambal matah. Keep at room temp if serving within hours.

- Make coconut rice early and rewarm gently with a splash of coconut milk.

- Soak rice noodles and drain just before frying.

Right before guests arrive:

- Preheat grill or broiler.

- Lay out herbs, lettuces, lime wedges.

- Set up a noodle station: sauce measured, protein ready, pan warming.

Service:

- Grill skewers first and rest them. While they cook, someone pounds salad in a mortar.

- Fry noodles in two fast rounds while guests watch; pan theatrics are part of the party.

- Fold banh xeo to order so the thunder stays crisp.

- End with sticky rice and a platter of sliced mangoes warmed by the room, or pass a basket of sugared turon that crackles in the hand.

If you want the neighborhood to feel like Maxwell meets Vinh Khanh, put a fan in the window, play the sound of rain on tin, and let people eat standing up over the kitchen counter. It is the only right way to balance a bowl in one hand and a skewer in the other.

Small techniques that taste like a stall

- Fried shallots: Slice shallots thin and fry low and slow in a wide pan of oil until blond, then watch like a hawk. They go from pale to amber to perfect in a blink. Drain on paper, salt lightly. Save the oil—the perfume is chef’s gold.

- Wok hay without a jet burner: Preheat pan to smoking, then add oil and aromatics for just a breath before the main ingredients. Never overcrowd. Let portions sit undisturbed for 10 to 20 seconds to sear before stirring.

- Lime management: Squeeze limes with the cut side up to keep seeds out, and add acid at the last moment for brightness. Zest is welcome in batters and marinades.

- Herb handling: Pluck herbs in big, lazy leaves. Street food is not chiffonade; it is fistfuls.

- Sugar in sauces: Melt sugar in warm water or in hot oil for sambals before adding liquids; granules that do not dissolve will sand your sauce.

Stories from stalls that follow you home

At Chiang Mai’s Chang Phuak Gate, the cowboy-hatted lady ladles pork leg braise over rice, a sauce so glossy it mirrors the stall lights. The meat is soft but never apologetic, the pickled mustard greens a contrapuntal bite. Back home, I braise pork with soy, star anise, cinnamon, and palm sugar, then lay it over rice with a soft egg and a tangle of greens. The cowboy hat is not essential, but the rhythm is: fat, salt, sugar, vinegared crunch.

In Saigon’s District 4, snails clatter in metal bowls while cooks toss them with lemongrass and chili, the scent of lime leaves cutting through city heat. I cannot find those precise snails at my market, but clams sing the same melody when steamed with lemongrass and a split chili and then blanketed with herbs. The broth is a tonic; a small bowl of nuoc cham on the side turns it into a ritual.

On Penang’s Gurney Drive, the char kway teow master works a narrow heat window: the noodles rip and repair in a breath, eggs scramble and cling, bean sprouts stay alive. My home pan will not do exactly that, but a small batch, a hot pan, and permission to let some noodles sit still until the edges taste caramel are close enough to make me grin.

Memory is a spice rack. Use it liberally.

The street is not a place; it is a way to cook and eat that leaves room for speed, imperfection, and generosity. When the chilies sting and the lime makes your molars sing, when a skewer drips on your wrist and you laugh because there are no napkins within reach, when you pass a bowl to the person next to you and they add a leaf of basil you missed—then you are there, even if your feet never leave the kitchen tile. Light the pan, trust your nose, and let the market come to you.