Patagonian Flavors Wild Game in Argentine Cuisine

33 min read Explore Patagonia’s rugged larder—guanaco, ñandú, wild boar, and red deer—through Argentine techniques, smoky fires, and regional wines, balancing tradition, terroir, and sustainable, respectful hunting. January 07, 2026 07:06

Patagonian Flavors: Wild Game in Argentine Cuisine

The first time I tasted guanaco, the wind was doing its stern Patagonian thing—leaning against the side of an old estancia house near El Calafate and whistling through the poplars like a kettle about to sing. Inside, a Dutch oven ticked and sighed on a blackened stove. The stew inside was dark as mahogany, perfumed with bay leaf and the resin-sweet smoke of lenga wood. There was a sour-sweet brightness too—rosehip, someone told me—and a softness that surprised me: guanaco, lean and quick on the steppe, rendered tender by patience, by wind, by time.

That night I learned something essential about Argentine Patagonia: the place seasons the meat. The wind stunts shrubs into spice cabinets. The cold sharpens edges. Smoke adds warmth that the air will not. When people talk about Argentine cuisine, they often go straight to the grasslands and the beef. But head south, and the meat changes voice. It whispers of berries and frost, resin and ash, thyme growing low among rocks, and the quick thrum of wild hearts: guanaco, red deer, wild boar, hare, and the rare, dignified rhea.

Where the Wind Seasons the Meat: Landscape and Terroir

All cuisines are terroir in action, but few show it as starkly as Patagonia. Think of it as a long inhale of openness—steppe that unspools into horizon, Andean spines that drag clouds by their bellies, lakes the color of polished slate. On the western edge: lenga and ñire forests whose wood burns hot and aromatic, and in autumn, mushrooms (morillas, hongos de pino) sprout among the needles like secrets. On the steppe, thyme and paramela brush your shins; their oils ride the air. In spring, rosehip (rosa mosqueta) catches in your sleeves as you walk.

These plants are more than scenery. They are the pantry that writes itself into the meat. Wild boar fat collects the taste of mast and roots; red deer graze on alpine grasses; hare’s sprinting muscle is tight-grained and mineral-sweet. Guanaco, the camelid native to these latitudes, tastes a little like venison if it had spent a summer combing wind from its fur, a finer game perfume, leaner, more herbal.

And then there’s the wood. Lenga and ñire have a scent like toasted honey and clean resin. When they smolder, they give game the kind of smoke you taste as much in your nose as on your tongue—warmth with edges. Patagonians don’t often fuss with heavy sauces; the landscape has already done the seasoning, especially when meat meets flame.

From Tehuelche Trails to Estanciero Tables: A Brief History of Game

Before Patagonia was plotted on postcards, the Tehuelche and Mapuche peoples read the land as a living cookbook. They tracked guanaco across basalt plains, dried the meat into charqui under halved moonlight, and honored the animal’s spirit with the same care as the flesh. When European settlers arrived—Welsh in the Chubut valley, Italians and Germans in the Andean lake district—they brought sheep and cattle, yes, but also a taste for the chase and for preservation.

Red deer (ciervo colorado) and wild boar (jabalí) were introduced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, thriving in the Andean foothills and the forested folds around Bariloche and San Martín de los Andes. Hare (liebre europea) took to the steppe like a footnote that became a chapter. Over time, these newcomers seeped into local cookery, especially in curados y ahumados—cured and smoked meats—that you still find in deli counters around the lake district: slabs of ciervo ahumado, boar salami, a glistening pink of smoked trout tucked in among the darker game.

Guanaco, native and noble, has always had a special, sometimes complicated place. It’s emblematic of the south—its silhouette a kind of moving punctuation mark against endless sky. Today its harvest is tightly regulated; in some provinces it’s protected entirely, in others controlled culls support populations and local economies. When you see guanaco on a menu in Patagonia—say, in Ushuaia or Río Gallegos—chances are it’s part of a legal program that emphasizes whole-animal use and waste reduction. The story of wild game here is one of adaptation: of indigenous knowledge interwoven with immigrant craft, of invasive species reclaimed by the pot and pan.

Meet the Animals: Flavor Profiles of Patagonia’s Game

If you read a piece of meat like a landscape, you’ll find Patagonia already written in these cuts.

-

Guanaco: Lean as wind. The color runs ruby to garnet, the grain fine, the flavor an elegant venison—clean, with a meadowy whisper. Overcook it and it tightens; treated gently, it glows. I’ve had guanaco in two moods: raw, paper-thin, with calafate berries and olive oil at a lakeside bistro near Bariloche; and braised, in the kind of stew that turns cold weather into appetite. Both made sense: one showed the animal’s delicacy, the other its endurance.

-

Red deer (Ciervo colorado): Slightly more robust than guanaco, with an earth-damp aroma that’s loveliest in autumn when the woods smell the same. Roasted haunch is a lodge classic; a slab of backstrap seared and basted with brown butter and tomillo patagónico will perfume the room.

-

Wild boar (Jabalí): The fat is the story. Not bland pork sweetness, but a foresty succulence that tastes of roots and stray pine. Boar loves smoke; it loves garlic and Merlot; it loves being turned into chorizo with a prickle of ají molido, or confited until it shreds under a fork like polite pulled pork that spent a year in the woods.

-

Hare (Liebre): Springy, copper-sweet, and quick to toughen if you chase it with too much heat. Pickled in escabeche—vinegar, bay, peppercorns, a nip of olive oil—it becomes a pantry treasure, tangy and plush on bread. Braised with wine and a tomato’s haunted sweetness, it pleases those who say they don’t like “game.”

-

Rhea (Ñandú or Choique): Rarely seen on menus because of conservation concerns, but some farms raise them. When you encounter it (ethically sourced), think very lean, dark poultry. It fares well ground—think spiced albóndigas—or as cutlets taken only to blush.

You’ll also find unusual birds on some tables—partridge (perdiz), Andean geese—though these are less common in restaurants. In most cities, the public face of game is charcutería: ciervo and jabalí sliced thin, salted just so, and leaned against a lineup of jam jars: calafate, cassis, rosa mosqueta.

Fire, Smoke, and Time: Techniques That Define the Plate

Argentine cooking honors the line between raw and incinerated with an almost musical sense of timing. In Patagonia, the orchestra is wood and wind. The three most telling techniques for game are:

-

Asado a la cruz (or a la estaca): A dramatic, upright roast where meat—traditionally lamb, but boar legs and deer haunches turn beautifully—is splayed on iron crosses around a slow fire of lenga embers. The heat is indirect, more caress than blaze. The outside lacquer develops from slow basting (salmuera—salty water with herbs), while the inside climbs to doneness as if it had decided to do so on its own. Game’s lean cuts can be swaddled in caul fat or barded with lamb tallow to protect them from wind and dryness.

-

Ahumado (Smoking): Cold smoking with lenga is a regional signature, particularly around Bariloche and Villa La Angostura. Ciervo ahumado emerges the color of dusk, with a perfume that’s all resin and restraint. Boar bellies take to warm smoke like they were born to it. The key is patience—hours where you let wood talk.

-

Guisos y estofados (Stews and braises): Because many cuts of game are athletes rather than loungers, they reward long, slow cooking. A guanaco estofado with Pinot Noir, crushed juniper, rosemary, and rosehip is a day’s work that tastes like three winters learned by heart. Hare and deer shoulders collapse into sauce that clings to polenta or a heap of papas rotas.

A few add-ons make these techniques sing: a marinade that balances game’s lean muscle with acid (wine or vinegar), a careful hand with salt, and herbs that smell like the ground they came from—tomillo patagónico, laurel, a whisper of Mapuche merkén for smoke and heat.

A Night in Trevelin: Field-to-Table Story

Trevelin wears its Welshness like a knitted shawl—cable-knit teahouses, rose gardens, English names dusted onto Patagonian hills. I went in autumn, the air a handsome chill. A local guide named Miguel kept a rifle in the truck—not for cinema, but for rabbits chewing through his garden and for the occasional hare. He talked about his grandmother who brought a brass urn and a sponge cake recipe across oceans, and how she learned to make escabeche because Patagonian hares, unlike Welsh rabbits, demand vinegar to soften their sprint.

We drove along a gravel road striped with poplar shadows, and I watched a pair of rheas sprint across a field, their feet writing cursive into dust. “Not ours,” Miguel said, nodding at them. “We let them be.” We pulled into a friend’s field house that smelled of apples and last year’s smoke. In the kitchen, a pot of deer stew—ciervo from an earlier hunt—had been murmuring on the stove all day. The sauce was brick-red and collected light in a way that made you want to put your face in the steam.

Dinner went as Patagonia goes—unhurried, wind-scored. We ate ciervo with spoonable polenta, and later, a plate of liebre en escabeche, silky and bright, its vinegar softened by olive oil and crushed bay leaves. Between mouthfuls, the talk drifted from the berrea—the deer’s autumn rut, when antlers and calls hum in the valleys—to the methods that make you a decent guest at a wild table. Don’t take what you won’t use. Share what you make. Remember which road the wind took.

When we left, the stars sewed themselves back into the sky. I tucked a jar of escabeche into my bag and drove away with the windows cracked to let the stew smell ride the night.

Where to Taste It Now: Restaurants, Estancias, and Markets

If you’re traveling through Argentine Patagonia with a curious fork, there are kitchens that speak fluent game.

-

Ushuaia: Chef Jorge Monopoli’s Kalma Resto has been known to plate guanaco with quiet reverence—rosy slices next to berries and smoky purées that taste like the landscape on a good day. For asado de cordero (not game, but an essential contrast), La Estancia offers lamb grilled a la cruz, perfect for understanding the local fire language before moving on to wild flavors.

-

El Calafate: Estancia Nibepo Aike is a postcard of Patagonian ranch life and a masterclass in patient fire. Ask about seasonal game—sometimes boar appears, and the lessons about wood and wind apply across species. In town, La Tablita is famed for lamb, but specials can include ciervo in autumn.

-

Bariloche and the Lake District: Cassis, on the road to Villa Arelauquen, is a temple to delicacy. Chef Mariana Müller works with local berries and herbs; I’ve eaten venison there kissed with calafate and a sauce drawn so thin it seemed lit from within. For smoked game, delicatessens like La Familia Weiss have long counters of ciervo and jabalí ahumados, and Cervecería Patagonia’s taproom occasionally runs dishes that flirt with boar and berry.

-

San Martín de los Andes/Junín de los Andes: In March and April, the berrea brings hunters and chefs into whispered conspiracy. Lodges around Chapelco serve red deer in roasts and ragùs. Ask for local menus; the cooks know. Markets often offer jars of liebre en escabeche alongside calafate jams.

-

Río Negro Valley (General Roca, Cipolletti): Wine country has a way of treating game with respect. At Bodega Humberto Canale’s restaurant, seasonal menus sometimes tilt toward boar ragu and venison terrines. Bodega Chacra and Noemía don’t always host kitchens open to the public, but the bottle shops suggest pairings that read like recipes. In Neuquén’s San Patricio del Chañar, the restaurant at Familia Schroeder (Saurus) threads Patagonian flavors into its courses—watch for boar and mushroom pairings.

Even when game isn’t on a lunch menu, you’ll feel its presence. Markets sell coils of jabalí chorizo, vacuum packs of ciervo ahumado, jars of paramela honey, and calafate liqueur lining up like blue-black soldiers.

What to Pour: Patagonian Bottles and Brews That Love Game

Wine has been growing roots in Patagonia for over a century, and the region’s cool climate draws out finesse that flatters game.

-

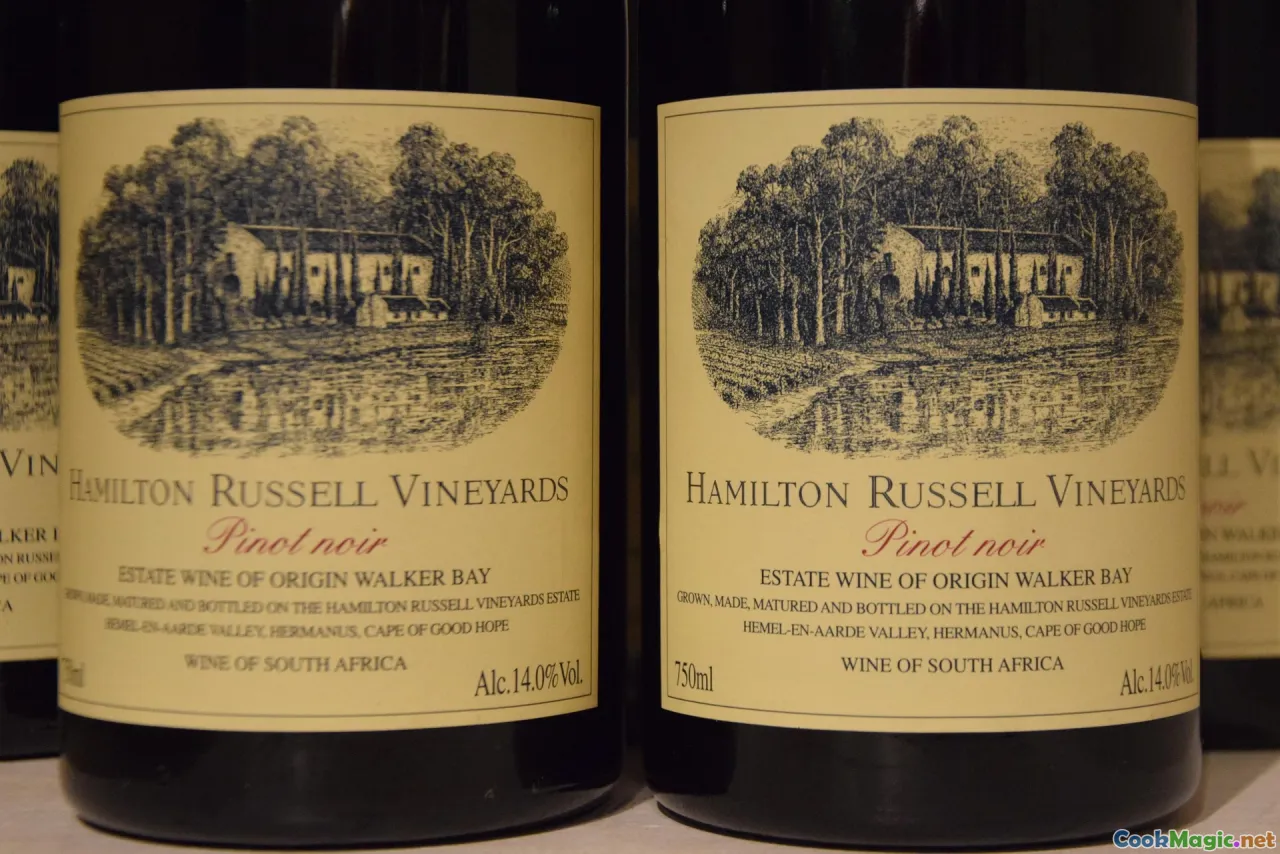

Pinot Noir from Río Negro and Neuquén: Transparent, red-fruited, and a little herbal—think Bodega Chacra’s Burgundian whisper or Saurus Barrel Fermented’s layered cherry and spice. Slices of guanaco or venison carpaccio glow under a wine like this.

-

Merlot and Cabernet Franc: Humberto Canale’s Merlot has a plummy spine that wraps around boar ragù like a shawl. Cabernet Franc, now a darling in cool climates, brings redcurrant and green spice that locks into the wild herb notes in game.

-

Malbec, but Patagonia-style: Noemía makes a perfumed, high-toned Malbec that’s a far cry from Mendoza muscle—perfect for stews without smothering them.

-

Whites: Don’t overlook a firm, mineral Chardonnay with rhea or with venison tartare. The acid lifts; the oak, when gentle, frames.

-

Beer: Patagonia’s brewing scene is as alive as its wind. Bariloche’s Berlina pulls a smoky rauchbier that throws arms around boar sausage. El Bolsón’s small breweries do hop-forward ales that scrub the palate after stews.

-

Spirits: Calafate liqueur is folklore and dessert in one sip—drink it neat or dashed onto vanilla ice cream. Bosque Gin from the Bariloche area captures Patagonian botanicals—paramela among them—and sings beside a charcuterie board of ciervo ahumado.

The best pairings echo something inherent: berry with berry, smoke with smoke, herb with herb. When in doubt, look out the window and pour what the landscape suggests.

Cook This at Home: Two Rustic Game Preparations

You don’t need a Patagonian forest to cook like one. You need patience, good sourcing, and a compass for flavor.

Guanaco Estofado with Pinot Noir and Rosehip

Serves 6–8

- 1.5 kg guanaco shoulder or leg, cut into large cubes

- Salt and black pepper

- 2 tablespoons ají molido (Argentine red pepper flakes), mild

- 2 tablespoons olive oil

- 2 onions, finely chopped

- 3 cloves garlic, sliced

- 2 carrots, diced

- 2 bay leaves

- A few sprigs tomillo patagónico (or regular thyme)

- 500 ml Pinot Noir (Patagonian if you can)

- 500 ml beef or game stock

- 2 tablespoons rosehip jam (rosa mosqueta), or 1 tablespoon if very sweet

- 1 teaspoon crushed juniper berries (optional but lovely)

- A strip of orange zest

Steps:

-

Season the guanaco generously with salt, pepper, and ají molido. Let it sit at room temperature for 30 minutes while you prepare the vegetables.

-

Heat olive oil in a heavy Dutch oven over medium-high. Brown the guanaco in batches until caramelized; don’t crowd. Remove to a plate.

-

Lower the heat to medium. Add onions and a pinch of salt; cook until they fold into themselves and turn sweet, about 8–10 minutes. Add garlic; stir until fragrant.

-

Return meat to the pot. Stir in carrots, bay leaves, thyme, juniper, and orange zest. Pour in the Pinot Noir and scrape any browned bits from the bottom. Let the wine simmer 5 minutes to soften its edges.

-

Add stock until meat is just covered. Bring to a whisper of a boil, then lower to a bare simmer. Cover and cook 2–3 hours, stirring now and then, until the meat yields to a spoon.

-

Stir in the rosehip jam; taste and adjust salt. The jam shouldn’t shout; it should lift. Simmer uncovered 10 minutes to let the sauce shine. Serve with smashed potatoes or creamy polenta, chopped parsley on top if you like green brightness.

Liebre en Escabeche (Hare in Vinegar Marinade)

Makes 2–3 jars; keeps in the fridge for weeks

- 1 hare, jointed (or 1.2 kg rabbit if hare is unavailable)

- Salt and black pepper

- 250 ml white wine vinegar

- 250 ml dry white wine

- 250 ml water

- 200 ml good olive oil, divided

- 2 carrots, sliced into coins

- 1 onion, sliced

- 6 garlic cloves, lightly crushed

- 2 bay leaves

- 1 teaspoon black peppercorns

- 1 teaspoon coriander seeds

- 1 small dried chile or 1 teaspoon ají molido (optional)

- Peel of 1 lemon (no white pith)

Steps:

-

Season hare pieces with salt and pepper. In a wide pot or sauté pan, heat 3 tablespoons of the olive oil over medium-high. Brown hare lightly on all sides; remove to a plate.

-

Lower heat. Add onion and carrot with a pinch of salt; cook until softened but not brown. Add garlic, peppercorns, coriander seeds, chile, and bay leaves; stir until fragrant.

-

Return hare to the pot. Add vinegar, wine, and water in equal parts (250 ml each). Bring to a simmer, then lower heat and cook gently, partially covered, for 45–60 minutes, until the meat is just tender.

-

Let cool slightly. Divide hare, vegetables, and aromatics into sterilized jars. Top with cooking liquid and enough olive oil to seal the surface. Add lemon peel. Seal and refrigerate once cool. It’s best after 48 hours; serve at room temperature with crusty bread.

Notes:

- With very lean game (guanaco, rhea), don’t skip fat. A spoon of lamb tallow or a drizzle of good olive oil at the finish is like a warm coat.

- For smoke without a smoker, char a piece of lenga or oak and drop it, extinguished, into your pot for the last 5 minutes, covered. Or add a pinch of merkén.

Patagonian vs. European and North American Game: A Flavor Comparison

Comparisons are imperfect but useful. If you love European venison, you’ll find Patagonian red deer familiar, but the seasoning of place shifts the needle: the herbs taste wilder, the fat thinner, the meat cut with an alpine clarity. In North America, wild boar can veer feral, heavy with funk. Patagonian boar tends to be a shade cleaner, a product of diet and the prevalence of smoking and curing traditions that refine its edges.

Hare is a touchstone: British jugged hare is port and gutsiness. Patagonian liebre favors sunlight—a balancing act of vinegar, bay, and olive oil that flatters the meat’s iron. Where Central European game leans on juniper and cream, Patagonia seeks lift: berry acidity (calafate, cassis), herb brightness (thyme), and the gentle insistence of wood smoke that never dominates, only frames.

And guanaco? There’s no perfect analog. If venison is a violin, guanaco is a viola—deeper and yet somehow lighter, an elegance with muscle beneath. Treat it like you’d treat your best wild deer tenderloin: sear to medium-rare, rest, slice, finish with salt that crunches.

On the Wild Side, Responsibly: Seasons, Ethics, and Sustainability

The most delicious bite is the one you can eat with a clear conscience. Patagonia makes this easier—and more complex.

-

Regulations vary by province: In Tierra del Fuego and Santa Cruz, guanaco harvesting is regulated through permits; in others it’s entirely protected. Red deer and wild boar, being invasive, are more commonly hunted under controlled seasons. Always ask where meat comes from. Ethical restaurants will tell you.

-

The berrea (red deer rut) happens around March–April. Hunts are often organized near Junín and San Martín de los Andes. If you hunt, choose outfitters who prioritize animal welfare and full utilization, and who collaborate with provincial authorities.

-

Nose-to-tail is more than a trend here. Estancias that process game well use bones for fonds, fat for confit, trim for sausage. Smoked and cured products extend shelf life and tradition. When you buy, look for producers who can explain their process.

-

Indigenous knowledge matters: Mapuche and Tehuelche practices built sustainable relationships with the land long before refrigeration. Respect closures of sacred sites and follow local guidance in wild plant foraging (paramela, calafate, mushrooms) to avoid overharvesting.

-

At home: If you’re not in Patagonia, source ethically farmed or legally hunted equivalents. Many flavors translate beautifully: venison for guanaco, wild pork for jabalí, rabbit when hare is unavailable. Treat the idea—wind, wood, acid, herb—as your compass.

A quick checklist for buying and cooking game responsibly:

- Ask for provenance; prefer producers who provide permits or traceability.

- Check dates—frozen game should be vacuum-sealed, labeled with harvest and pack dates.

- Avoid excessive packaging with “wild” claims but no details.

- Cook lean cuts kindly—medium-rare to medium—and let them rest.

- Balance meat with berries, acidity, and herbs rather than creamy cloaks; let the landscape show.

Notes on Flavor Memory: Why Patagonia Stays With You

I left Patagonia with a pocket full of receipts and a notebook that smelled faintly of smoke. Weeks later, a forgotten scarf still whispered of tomillo and ash. That, I think, is the spell of this place: it writes itself onto your senses and then lingers—on your tongue as a sweet-metal echo of hare, in your nose as lenga’s honeyed soot, behind your eyes as guanaco stepping like punctuation across a line of horizon.

There are cuisines that sing in taverns and those that hum in plazas. Patagonian game sings best outside, with wind as percussion. Meat against fire, a glass that catches last light, someone telling a story about a grandfather who tracked deer by sound. You learn to lean into the elements: to use acid when the meat asks, to be patient when the muscle demands it, to respect the animal whether it’s native royalty or an immigrant made welcome by the pot.

If you travel south, take an empty notebook and a flexible appetite. Ask old questions—what’s in season, who hunted this, what wood do you burn—and write down the answers alongside what you tasted. Eat a slice of ciervo ahumado on toasted bread with calafate jam and a smear of good butter. Try guanaco if it’s offered from a reputable source, and listen to the quiet after you swallow; sometimes it sounds like wind leaning against a fence. Bring home a jar of liebre en escabeche and a bottle of Pinot Noir that remembers the cold.

And if you can’t go, cook anyway. A cast iron pot can hold more landscape than you think. A handful of herbs, a pinch of smoke, a careful pour of wine—these are coordinates. Patagonian game is a map you taste, and the way home is always the same: follow the wind, trust the fire, season with memory.