How to Serve a Traditional Armenian Breakfast Spread

40 min read Plan an inviting Armenian breakfast spread with lavash, cheeses, herbs, jams, and basturma, plus serving tips, plating ideas, and beverage pairings for a convivial, culture-rich morning table. October 08, 2025 18:08

The first time I understood how a morning could smell like a place was in Lori, where the light is the color of apricot skins and the air tastes faintly of woodsmoke. I woke to the rustling of lavash slapping the walls of a hot tonir and the quick staccato of a knife chopping herbs. Someone had already walked through the orchard, heaping a basin with vine-ripe tomatoes and cucumbers still cool with dawn. A slab of salty cheese was sweating on the table, a curl of string cheese hung from a peg like a white lasso, and a small copper pot of coffee simmered until its surface swelled into a brownish velvet cap. That is the soundscape of a traditional Armenian breakfast: a low, generous hum built from bread, dairy, herbs, and the quiet seriousness of hospitality.

In Armenia, breakfast can be as spare as bread and cheese or as ceremonious as a winter khash feast. It can mean a quick weekday plate of matsun and fruit, or a long Sunday table stitched with preserves from last summer and stories from last century. The ingredients are simple; the meaning is not. To serve an authentic Armenian breakfast spread, you don’t just assemble food—you create a morning that remembers.

What Makes a Traditional Armenian Breakfast Spread

At its core, the Armenian breakfast is about balance and abundance rather than heavy cooking. Think of it as a composed still life where everything is meant to be torn, dipped, pinched, folded, and shared. The main pillars are:

- Bread and warmth: fresh lavash or matnakash, often warmed gently and kept tender in a cloth.

- Cheese and dairy: salty brined cheeses, stringy chechil, tangy matsun (yogurt), sometimes clotted cream.

- Herbs and crisp produce: green tarragon, purple basil, parsley, radishes, green onions, tomatoes, cucumbers.

- Preserves and sweetness: apricot jam, white cherry preserves, fig or walnut moraba, honey, and doshab (mulberry or grape molasses).

- Proteins and comfort: eggs with basturma or sujuk; on special mornings, a pot of spas (warm yogurt soup), or in winter, the early ritual of khash.

- Beverages: black tea, mountain herb infusions, and Armenian coffee brewed in a copper jezve.

What ties these elements together is a rhythm of contrasts—salty against sweet, warm next to cool, soft bread with crunchy herbs—supported by an etiquette of generosity. You fill a plate for someone else before you fill your own. The first lavash from the cloth is offered to the elder at the table. Coffee grounds are read for luck after the last sip. These gestures matter as much as the flavor.

Bread Is the Beginning: Lavash and Matnakash

Lavash, the paper-thin flatbread baked on the curving wall of a clay tonir, is the backbone of Armenian mornings. It is UNESCO-listed not just as bread, but as a communal practice. In villages, women gather to roll, stretch, and slap dough onto the tonir’s inner walls, pulling it off in sheets that float like linen and crackle as they cool. Nothing smells like fresh lavash—yeasty, slightly smoky, and toasty all at once, with edges that snap and centers that yield.

Matnakash, the hearth bread with a shiny, ribbed surface, brings a different pleasure: a tender, sesame-scented crumb, perfect for dragging through honey or pressing into cheese. Either bread is appropriate for breakfast, but lavash has a special talent for assembling bites. Tear a sheet into quarters and you have edible plates for cheese and herbs. Fold a wedge around basturma and tomato and you have a handheld sandwich that tastes like a field meal.

How to serve the bread:

- Warm lavash: Flick a few drops of water onto each sheet and wrap in a clean cloth; warm briefly in a low oven. This revives day-old lavash to a tender suppleness.

- Keep it breathing: Store warm bread in a bread basket lined with linen. If you trap steam, it becomes chewy; if you lose all humidity, it dries and shatters.

- Matnakash slices: Cut thick slabs and toast lightly if they’re a day old; brush with a whisper of butter only if you’re veering into indulgent territory.

A ritual I love: tuck a hot slice of matnakash into the hollow of your palm, spoon on thick matsun, sprinkle it with chopped dill and a few grains of coarse salt, then fold it closed. The bread warms the yogurt; the yogurt perfumes the bread. This is simplicity with a pulse.

The Cheese Board: Salty, Tangy, and Stringy

Armenian breakfast cheese is not a timid affair. It is bold, brined, and built to spar with herbs and tomatoes. Assemble a board with contrasts in texture and saltiness:

- Lori or Chanakh: Firm, crumbly, briny cheeses from cow or sheep’s milk. Expect a clean lactic tang, a salty punch, and a crumb that wants to scatter into little pearls across your plate.

- Chechil: The beloved string cheese, often braided. Its texture is fibrous and squeaky, with a mild creaminess. Untangle strands and twirl them into herbs for the most pleasing bite of the morning.

- Motal (if you can source it): A sheep or goat cheese traditionally aged in clay jars or skins. It brings a pastoral aroma and a slightly funky depth.

- Fresh farm cheese: Younger and softer, sometimes sold at GUM market in Yerevan, wrapped in gauze. It tastes like sunlit milk.

Pairings that sing:

- Watermelon and salty cheese in high summer—a plate that tastes like cool shade and warm stones.

- Grapes or figs with chechil—the snap of the grape skin against the fibrous cheese is euphoric.

- A drizzle of doshab on fresh cheese—the molasses stains the crumb and brings a slow, smoky sweetness.

Arrange the cheeses with sprigs of herbs nestled between them. Let them breathe at room temperature for 20–30 minutes before serving so their aromas bloom.

The Herb Plate: A Forest on the Table

Herbs at an Armenian breakfast are not garnish; they are a course. A plate of greens is called kanach and is often the most inviting color on the table. Combine:

- Tarragon: buttery and anise-like, it perfumes bites of cheese and eggs.

- Purple basil: slightly clove-like, with a lush hue that looks like velvet petals.

- Parsley and cilantro: bright, green, and cleansing.

- Green onions: snappy, with a juicy bite.

- Radishes: peppery crunch.

- Cucumbers and tomatoes: layered for their crispness and juice; choose tomatoes that smell like the vine.

Tips for crisp, cold greens:

- Wash herbs gently and spin dry, then hold in ice water for 5 minutes. Drain and wrap in a damp towel; chill until serving. This keeps stems perky and leaves glossy.

- Slice tomatoes at the last minute and sprinkle with a pinch of salt to pull their juices to the surface. Catch those juices with bread.

- Look for Armenian cucumbers, slender and thin-skinned, at Middle Eastern markets; if unavailable, Persian cucumbers are a fine substitute.

When you compose a bite, use herbs like you would lettuce, in quantity. A proper mouthful of tarragon, basil, and parsley with a crumb of cheese and a wedge of tomato is a small, edible bouquet.

Eggs and Preserved Meats: The Sizzle and the Spice

Armenia knows the power of cured meats in the morning. Basterma (air-dried beef coated in a fenugreek and spice paste called chaman) and sujuk (a garlicky sausage) bring a rosy, smoky perfume to the air when they hit hot fat. They are classic partners for eggs.

Basterma and eggs, a skillet method:

- Slice basturma paper-thin; its edges should be translucent with fat. Heat a slick of butter or ghee in a skillet over medium heat.

- Lay the basturma slices in the pan for 30–45 seconds, just until they release their aroma and the chaman wakes up. Do not crisp it to leather; basturma turns bitter if overcooked.

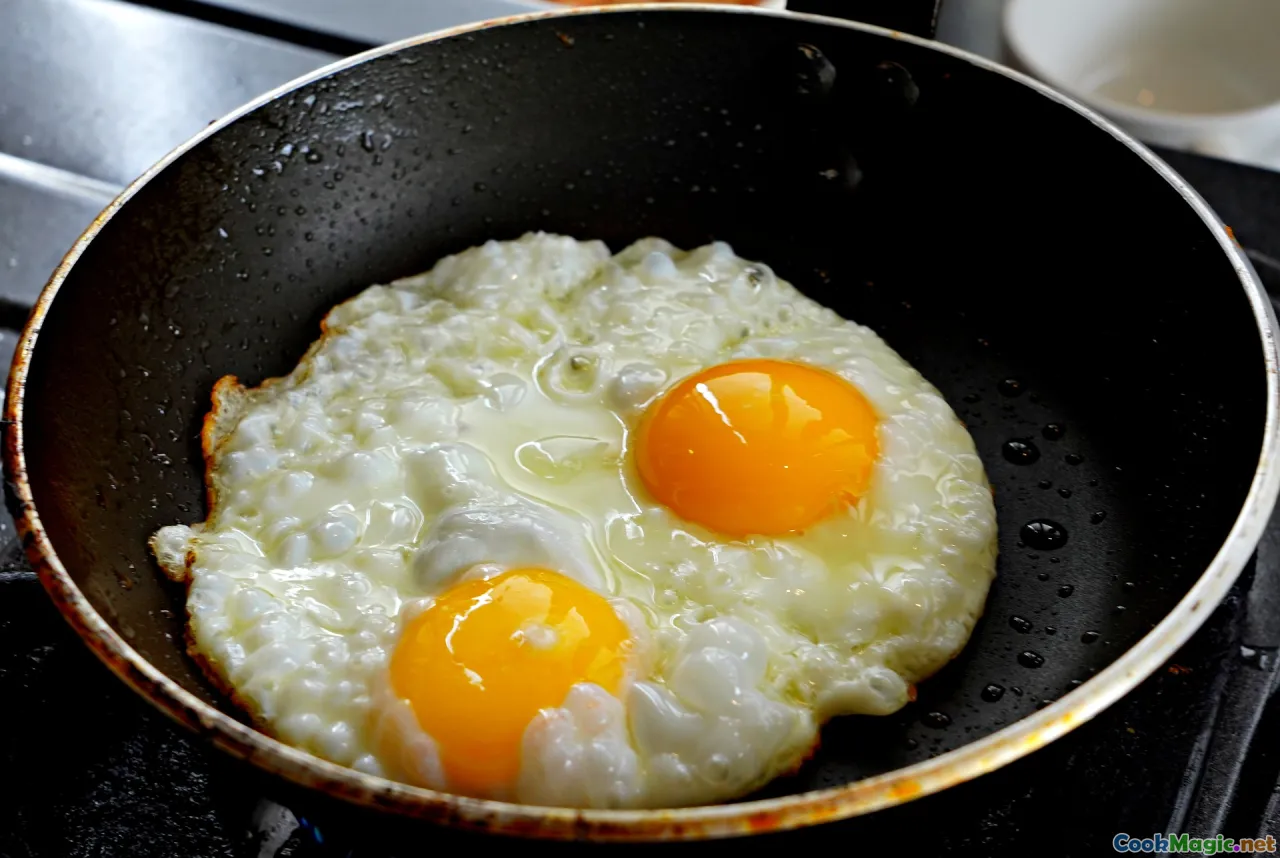

- Crack eggs directly over the meat. Lower the heat to medium-low, cover briefly to steam, and cook until whites are just set and yolks still runny.

- Spoon off some of the orange, fenugreek-stained butter from the edges and ladle it over the eggs. Finish with black pepper.

Sujuk and eggs:

- Slice sujuk into thick coins and cook in a dry skillet on medium heat until the fat renders and edges curl—smells of garlic, pepper, and smoke.

- Remove some of the oil if the pan floods; crack eggs into the caramelized fat and scramble, or cook sunny-side-up right on top.

Tomato-egg scramble, a lighter option:

- Soften a chopped onion in butter with a pinch of Aleppo pepper.

- Add peeled, chopped tomatoes and cook down until jammy.

- Crack in eggs and scramble gently until just creamy. Finish with tarragon.

A word on sourcing: basturma and sujuk vary widely. In Yerevan, specialty shops near the Vernissage or stalls at GUM market sell artisan versions. Abroad, Armenian and Middle Eastern grocers often stock quality brands. Buy from reputable sources, and keep basturma well wrapped; its perfume is assertive.

Yogurt in Bowls and Pots: Matsun, Spas, and the Comfort of Warm Sour

Matsun, the Armenian cousin of yogurt, has a denser body and a gentle sour that hovers between milk and lemon. At breakfast, it appears in bowls, sometimes with honey and walnuts, sometimes plain with a heap of cucumbers and dill and a trickle of olive oil. But Armenian mornings also know warm dairy.

Spas (also known as tanapur or tahnabour) is a warm yogurt-barley soup that straddles breakfast and lunch. It is fortifying but not heavy, like a scarf in the mouth.

How to make a breakfast pot of spas for four:

- Cook 1/2 cup pearl barley in salted water until tender; drain well.

- In a saucepan, whisk together 2 cups matsun with 2 tablespoons flour and 1 egg. The flour and egg are insurance against curdling.

- Set the pan over low heat and start whisking. Slowly add 1 cup water, then the cooked barley. Add a big pinch of salt.

- Bring to a bare simmer, stirring often and patiently. Do not let it boil. If it thickens too much, loosen with more water.

- Finish with a fistful of chopped dill and mint. Some families add a spoon of browned butter with dried mint for fragrance.

Serve spas warm, with a crack of black pepper and a squeeze of lemon for brightness if your matsun is mild. A torn corner of lavash dunked into the creamy tartness is a breakfast spoon in itself.

And then there is khash. Not an everyday breakfast, khash is a ritual of winter, usually eaten at dawn between November and March. It is a gelatin-rich broth made from slow-simmered cow’s trotters, traditionally enjoyed with piles of raw garlic, salt added at the table, and mounds of lavash that are crumbled and soaked until they become a porridge. The table often includes radishes, pickles, and vodka for toasts that warm the bones as much as the soup does. If you serve khash, you are not serving a spread; you are staging an event. Seats are set the night before, the pot simmers overnight, and the morning is a chorus of toasts to health, to ancestors, to good roads.

Preserves, Honey, and Morning Sweets

Armenia jars its summers. The breakfast table is the museum of that work. Open a cupboard in late autumn and you will find rows glowing like stained glass: apricot jam the color of a setting sun; white cherry preserves with their translucent, almond-scented fruit; figs steeped in syrup; humble quince, cut into ruby gems; and, if you are lucky, green walnut preserves that taste like spiced caramel with a whisper of tannin.

Serving suggestions:

- The walnut preserve with clotted cream (kaymak) on a slice of matnakash—soft, cool, and yielding under the spoon.

- Apricot jam and salted cheese: smear, press, and fold in lavash for a bite that toggles between salty and floral.

- Doshab drizzled over matsun with chopped walnuts.

- Gata or nazouk for special mornings: these buttery pastries are filled with a sandy sugar-butter-walnut mixture called khoriz. A small slice goes a long way with black tea.

If you cannot source kaymak, lightly whip heavy cream until just thickened and chill; the texture will not be identical, but the morning will forgive you.

Torshi and Brined Brightness

Though not as central in Armenia as in parts of the Levant, pickles—torshi—still find their way onto breakfast tables, especially in cities like Gyumri or Yerevan, where grandmothers pride themselves on their brining. Consider a small plate of:

- Pickled cabbage, slivered; crisp and sour.

- Cucumbers, tiny and firm, with garlic and dill.

- Tomatoes in brine; their skins wrinkle, their interiors turn savory-sour.

- Hot peppers, for those who like a jolt with their eggs.

The role of pickles is to reset the palate between bites of cheese and protein. Their acid sharpens the morning.

The Morning Cup: Coffee, Tea, and Mountain Herbs

Armenian coffee is a ceremony in a small cup. It is brewed in a narrow-waisted pot called a jezve, often copper, over low heat until a thick foam forms—a little cap of crema that should never boil over, only quiver.

Brewing Armenian coffee for two:

- Grind coffee to a fine, powdery sand. Use about 1 heaping teaspoon per small cup.

- Add to the jezve with cold water, roughly 75 ml per cup. Add sugar now if you use it; Armenian coffee is sweetened in the pot, not after.

- Optional: a green cardamom pod, lightly crushed, or a pinch of ground cardamom.

- Set over low heat. As the coffee warms, a ring of foam will rise. Just before it threatens to spill, pull it off the heat, let it settle, then return briefly to coax more foam. Do this two or three times for a thick, fragrant brew.

- Pour slowly to distribute foam, and allow grounds to settle in the cup for a minute before sipping.

Tea is also dear—especially herb teas from the mountains: thyme, mint, rosehip, and wild oregano. Thyme tea, poured amber and piney, smells like the sun on rock. In the north, families dry bunches of herbs and hang them in kitchens, the aroma whispering through winter.

Other drinks that complete the picture:

- Jermuk or Bjni mineral water, chilled.

- Tan, a salted yogurt drink, with ice and a bit of chopped cucumber and dried mint.

- Thick apricot nectar, cool and luminous.

Laying the Table: Textures, Heights, and Hands

A traditional Armenian breakfast spread is less about matching plates and more about tactile warmth. Think of the table as a landscape of textures.

- Use a plain linen cloth or a woven runner. White linen allows the colors of herbs and tomatoes to pop.

- Mix ceramics with copper or brass trays; a hammered metal plate under a bowl of preserves catches light like water.

- Offer small plates and many forks. Leave room for hands to tear bread and for elbows to lean.

- Keep lavash in a cloth-lined basket and place it within reach of everyone.

- Salt on the table is essential. Pepper, too, and a small dish of crushed dried mint.

Arrange by rhythm: cheeses opposite herbs, eggs near breads, preserves away from pickles, coffee near the head of the table. The elder or the host will pour the first cups and often offer the first toast—even if the toast is water or tea.

Sourcing and Substitutions Beyond Armenia

If you are not in Yerevan’s GUM market or the stalls of Gyumri, you can still assemble a faithful spread with smart shopping.

- Bread: Seek out lavash at Armenian, Persian, or Russian markets. If unavailable, use a high-quality Middle Eastern flatbread. For matnakash, a good bakery loaf with tender crumb will do.

- Cheese: Feta (preferably sheep’s milk) stands in for brined cheeses; string mozzarella or Oaxaca cheese can mimic chechil’s pull; a young pecorino offers briny bite.

- Matsun: A whole-milk, lightly tangy plain yogurt works. Strain briefly for extra body. Some specialty shops sell matsun cultures if you want to make your own.

- Meats: Basterma and sujuk are widely available at Armenian and Middle Eastern grocers. If not, a high-quality, lightly spiced beef sausage can pinch-hit; season with fenugreek and paprika to nod to chaman.

- Herbs: Grow tarragon and basil if you can; otherwise, buy them the morning of your breakfast so they are fragrant and bright.

- Preserves: Look for white cherry preserves and green walnut preserves in Eastern European markets. Apricot jam is easy to find everywhere; choose one with whole fruits if possible.

A Vegetarian and Vegan Path Without Compromise

An Armenian breakfast can be arrestingly good without meat or even dairy, especially during Lent, when many Armenians abstain from animal products.

- Vegan anchors: warm flatbread, olives, tahini swirled with doshab, roasted eggplant salad (ikra), grilled peppers, and a chickpea-tomato sauté scented with cumin and coriander.

- Herb emphasis: increase the herb plate and add wild greens if you can find them—sorrel (aveluk), purslane, and nettles, blanched and dressed in lemon and olive oil.

- Fruit and preserves: lean into figs, grapes, apple slices with walnuts, and apricot jam on warm bread.

- Drinks: thyme tea, mint tea, and black coffee hold everything together.

The trick is to keep salt, fat, and acid in balance. A sliver of salty olive against the sweetness of apricot and the pepper of radish replicates the same chord you get from cheese and jam.

Seasons on the Breakfast Table

The Armenian breakfast shifts with the calendar and with altitude.

- Spring in Tavush: first radishes, green garlic, tender herbs, matsun with baby cucumbers, and warm bread. The table smells like rain and sap.

- Summer in Ararat valley: tomatoes with hearts so soft they collapse under a knife; crisp cucumbers; watermelon and cheese; fresh apricots that leave jam on your wrists; basil in fat bouquets. Everything is eaten cooler than the air.

- Autumn in Artsakh: figs and grapes, walnut preserves, roasted peppers in garlic, the first cool mornings that invite a pot of spas. Baskets of quinces sit on the counter like ornaments.

- Winter in Shirak: khash mornings with steamed windows; honey crystallized and spread with a spoon; pickles; fresh bread carried under a coat from the bakery; strong coffee and stronger stories.

Adjust the spread to what weighs down market tables. Armenia cooks with what the ground remembers.

A Simple How-To: Build the Spread in 60 Minutes

A practical plan for a traditional spread for four.

The day before:

- Buy lavash and wrap in a towel; if it stiffens, it will rehydrate with steam when warmed.

- Pick up cheeses, basturma or sujuk, matsun, preserves, and herbs.

- Chill mineral water and apricot nectar.

Morning timeline:

- T-60: Chill a large bowl of water with ice. Wash herbs and radishes, pat dry, then crisp in the ice bath. Slice cucumbers and set aside. Slice tomatoes last.

- T-45: Set out cheeses to come to room temp. Arrange preserves in small bowls with clean spoons. Set up coffee cups and the jezve.

- T-30: Warm lavash gently in a low oven, wrapped in a dampened towel. Keep covered.

- T-25: Brew the first round of coffee; keep it warming on the lowest heat. Or, boil a kettle for thyme tea and steep a pot.

- T-20: Cook sujuk slices in a skillet; drain excess fat. Crack in eggs and cook as desired. Tent with foil to keep warm.

- T-10: Arrange the herb plate—tarragon, basil, parsley, cilantro, green onions—then add crisped radishes. Slice tomatoes and sprinkle with salt.

- T-5: Set the table: bread basket, cheese board, herb plate, preserves, pickles, eggs, drinks. Place salt and dried mint within reach.

- T-0: Invite everyone to sit, pass the bread first, and pour coffee. A short toast is fitting even at breakfast: Bari luys—good morning.

Two Sample Menus: Weekday Swift and Sunday Sumptuous

Weekday swift (30 minutes, feeds two):

- Lavash warmed in a cloth.

- Lori-style brined cheese and chechil.

- Herb plate with tarragon, basil, cucumbers, and tomatoes.

- Matsun with honey and walnuts.

- Apricot jam.

- Black tea or Armenian coffee.

Sunday sumptuous (90 minutes, feeds six):

- Lavash and thick-cut matnakash.

- Cheese trio: chanakh, chechil, and motal, with grapes and figs.

- Basterma and eggs, and a tomato-egg scramble.

- Spas with barley and dill, served warm in a tureen.

- Herb forest: tarragon, purple basil, parsley, cilantro, green onions, radishes.

- Pickles: cabbage, cucumbers, and tomatoes in brine.

- Preserves: white cherry, fig, and green walnut, plus a bowl of clotted cream.

- Doshab and honey.

- Armenian coffee, thyme tea, mineral water.

Small Touches That Change Everything

- Crush dried mint between fingers directly over warm spas or matsun; the scent is a plume.

- Rub a clove of cut garlic on a slice of matnakash before topping it with tomatoes and herbs.

- Warm the plates just enough that cheese softens on contact.

- Use a pepper grinder with coarsely crushed black pepper; the aroma rises like a curtain.

- Keep a small bowl of coarse salt on the table for pinching, not sprinkling. The tactile act connects the eater to the food.

A Story from Gyumri: The Table as a Quilt

In Gyumri, I stayed with a family who measured hospitality in plates. It was late October. The mornings were silvered with frost, and windows were ferned with tiny feathery ice. The mother unfurled a white tablecloth with the snap of a sail and began to set the breakfast like a quilt: squares of cheese, squares of jam, squares of bread, and intervals of herbs. The grandmother in a patterned scarf brought out pickled tomatoes so translucent they gleamed, and a copper pot of coffee whose surface was dark and unblinking. She dribbled coffee into the tiny cups with a hand that had folded more lavash in her life than I have words.

When we ate, nobody rushed. The grandfather made a neat package of tarragon and cheese inside lavash and pressed it so it would not slip. He told a story about a market stall in Leninakan days—what Gyumri used to be called—where the seller would slice cheese with a thread pulled from her apron hem. After coffee, the cups were turned and read; my future was apparently full of travel and an unexpected encounter with a white dog. I left with a jar of fig preserves wrapped in newspaper and a smell of basil in my hair. What I took most was this: the breakfast was not food alone. It was a ritual of memory, a cloth laid over the table to hold together the morning’s edges.

Etiquette, Gestures, and the Poem of the Cup

There is no rulebook, but these customs keep the breakfast grounded in its culture:

- Offer the first piece of bread to the elder at the table. If the baker is present, compliment the bread first—hats, then everything else.

- Pour coffee for others before yourself. If you sweeten, ask preferences; sugar is brewed in, not added later.

- If khash is served, do not salt it in the pot; the salting is personal and done at the table. Crush garlic fresh.

- Refill plates and cups; abundance is a form of love.

- Coffee-reading is optional but welcome. After the last sip, place the saucer over the cup, swirl gently, flip, and let the grounds slide and cool. Someone with a knack will read patterns—roads, eyes, trees—and end with a blessing.

Troubleshooting and Safety Notes

- Basterma bitterness: If your basturma tastes bitter, it likely cooked too long. Next time, bloom it only briefly in fat before adding eggs.

- Curdled spas: Keep the heat low and never let it boil. The flour-egg mixture stabilizes the matsun; add water slowly, whisking constantly.

- Limp herbs: Shock in ice water and dry thoroughly. Salt only at the table; salt draws moisture and wilts leaves.

- Bread too dry: Humidify with a sprinkle of water and wrap in a towel; warm gently. Never microwave lavash naked—it turns rubbery.

- Food safety: Use reputable sources for cured meats; store properly. Cook eggs to your preference, but be mindful when serving to elders or pregnant guests.

Cooking with Place: Named Ingredients and Markets to Know

- GUM market, Yerevan: a labyrinth of dairy counters, spice mounds, and towers of preserves. Ask for chanakh, taste before buying, and let the cheesemonger wrap it in waxy paper.

- Dilijan roadside stands: thyme and mint bundled and dried; jars of honey that smell like meadows.

- Meghri figs: if you see them in season, buy more than you need. They taste like the sun relaxing.

- Ashtarak apricots: often destined for jam; when ripe, they yield to a thumb and bleed fragrance.

Bringing these names to your table, even if you are not in Armenia, is a way of invoking landscape with plate.

Why It Matters: The Morning as a Bridge

When you serve a traditional Armenian breakfast spread, you do more than feed a crowd. You stage a small reunion between now and then, here and there. The food is humble—bread, dairy, herbs—but the gestures are grand. You pass the first lavash to the elder, you pour coffee until the pot is empty, you tuck basil into bread like a leaf into a book.

Of all the meals one could fuss with, breakfast is the most forgiving and the most intimate. It asks you to pay attention to temperature, to color, to scent, and to the company you keep. Put out a plate of salty cheese, a dish of apricot jam, a heap of herbs, and warm bread; the table will assemble itself into hours. Add a skillet of eggs with basturma or sujuk, a pot of spas when the mornings go cold, and a cup of coffee that foams like a small storm. The room will fill with the smell of home—even if you are far from it.

On the best mornings, there is a moment when everyone leans back, bread torn to crumbs, cups bottomed, and the light falls just right on the amber surface of a jar of honey. There, in that minute, the spread has done its work. It has reminded us that simple things—bread that cracks, herbs that bite, yogurt that soothes—can hold the day together. Serve it often, and serve it with a generous hand; the morning will remember.