Fermentation in Hungarian Pickled Vegetables

40 min read Explore traditional methods, science, and regional flavors behind Hungary’s beloved pickled vegetables—from kovászos uborka to csalamádé—with tips on brines, seasonings, and fermentation safety at home. October 06, 2025 15:07

The first time I smelled a proper Hungarian savanyúság stall, I was standing beneath the iron ribs of Budapest’s Great Market Hall, a cathedral for cabbages and peppers. Dill pollen danced in the air. A sour thundercloud of brine rolled over baskets of almapaprika, the little apple-shaped peppers so glossy they looked lacquered. A vendor in a blue smock, her fingers pale and puckered from brine, lifted a jar to the light: cucumbers trapped in green sunlight, dill umbrellas splayed, a loaf-end of rye melting into a foggy cap. “Kovászos,” she said, a single word that all but fizzed on the tongue.

I ate my first true Hungarian fermented pickle at a scratched zinc counter near Fővám tér: a kovászos uborka, sliced lengthwise with the insouciant speed of someone who has cut cucumbers all her life. The warm whisper of garlic, the wiry snap of a grape leaf’s tannin, the effervescence that prickled like mineral water—all of it made me stand up straighter. I had tasted pickles before. I hadn’t tasted time, sunshine, and street-dust summer inside glass until then.

What We Mean When We Say Savanyúság

Hungary’s love language for tang is savanyúság—an umbrella term for sour things that live alongside stews, breaded cutlets, and slabs of paprika-dusted sausage. Within that, there are two big families. One is vinegar-based pickles, ecetes savanyúság, swift and sharp, often used for cherry peppers stuffed with cabbage or pungent onions that slap the palate awake. The other family is what we came here for: the slow, living ferment, tejsavas erjesztés—lactic acid fermentation—where salty water and time coax vegetables into deeper versions of themselves.

Some classics you’ll meet across Budapest lunch counters and country kitchens:

- Kovászos uborka: summer-fermented cucumbers, sun-struck and bread-capped.

- Savanyú káposzta: cabbage transformed into silky tang, Hungarian sauerkraut.

- Csalamádé: mixed shredded vegetables fermented as a wintry salad that squeaks and sighs.

- Almapaprika in brine: mild, thick-walled apple peppers, sometimes fermented, sometimes vinegar-pickled, always a painterly red or lemony yellow on the plate.

- Vegyes vágott: a medley of peppers, green tomatoes, carrots, onions, and cabbage, brine-kissed and barrel-aged in some kitchens.

My own first Hungarian kitchen was a narrow, tile-lined rental in the VIII district, with a balcony just big enough for two chairs and a 5-liter uborkás üveg—the tall-necked glass jar that looks like a carafe built for a family of giants. That jar became my teacher.

The Living Chemistry: Salt, Sun, and the Slow Crescendo of Lactic Bacteria

Fermentation in Hungarian pickled vegetables is carefully controlled chaos. We feed and shelter Lactobacillus and their friends, who prefer brine in the 2 to 3 percent range, darkness or diffused light, and temperatures not too chilled, not too hot. They digest sugars in the vegetables and exhale lactic acid, carbon dioxide, and a symphony of aromas: bread crust, green apple, wood cellar, dill pollen, garlic breath.

- Salt: It suppresses undesirable microbes while keeping the crunch by drawing out water and strengthening pectins. In most Hungarian households I’ve cooked with, the rule of thumb for cucumbers is roughly 1 level tablespoon non-iodized salt per liter of water, which puts you around 2 percent by weight. For cabbage, you’ll use 2 percent salt by weight of the shredded leaves.

- Temperature: Kovászos uborka thrives around 22 to 28 degrees Celsius. Below 18 C, fermentation stutters; above 30 C, it gains a reckless speed that can turn cucumbers mushy. Cabbage ferments happily around 18 to 22 C.

- Oxygen: The magic is mostly anaerobic. We submerge the vegetables under brine and weigh them down. The bread on kovászos acts like a microbial starter and a temporary raft, but the cucumbers themselves must stay underwater.

- Tannins: Grape leaves, sour cherry leaves (meggy), oak leaves, and horseradish leaves are traditional crispness-keepers, their tannins binding with pectin.

Watch a Hungarian courtyard in July and you’ll see jars set out like small observatories, catching light. The ferments burp lazily by day and sleep by night. On day two, a hiss escapes when you tilt the jar. By day three, brine turns cloudy and smells like young cider and hot sidewalks after rain. The sound when you bite a cucumber is audible—an eager fracturing—and the inside tastes carbonated.

Kovászos Uborka: Summer Fermentation, Sun in a Jar

There are as many kovászos uborka methods as there are Hungarian balconies. This is the one I learned in a Vecsés garden at the end of June, when the cucumbers curve like commas and lilies are near collapse in the heat.

What you need:

- 2 kg small, firm cucumbers (uborka) with dense seeds, ideally 8–12 cm long

- 2 liters non-chlorinated water

- 40 to 50 g coarse non-iodized salt (2–2.5 percent)

- 1 large bunch dill with flower heads

- 5 to 7 garlic cloves, halved

- 4 to 6 grape or sour cherry leaves (or 2 horseradish leaves)

- Optional: a thumb of horseradish root, peeled and sliced lengthwise

- A crusty heel of good rye bread, preferably 2 days old

- A 3 to 5 liter glass jar with wide mouth

The process:

-

Scrub the cucumbers until they squeak. Trim just the blossom end by a millimeter; leave the stem end intact. Slit each cucumber lengthwise twice or three times without cutting fully through—like a fan. This helps the brine soak the center.

-

Dissolve salt in water. Taste: it should be assertively salty, like the sea after a storm, but not mouth-drying. If you measure in volumes, start with 1 tablespoon per liter, but use your senses and adjust—Hungarian cooks do.

-

Pack the jar in layers: leaves, a quilt of dill heads, garlic, cucumbers, more dill, more garlic. Tuck horseradish root in if using. The jar should be snug, as if the cucumbers are waiting for a nap.

-

Pour brine to cover, leaving a few centimeters headspace. Push everything down with a hand, then top with the rye bread wrapped loosely in a cheesecloth or a thin gauze to keep crumbs tidy. The bread supplies yeast and lactic bacteria; it also smells like home.

-

Cover the jar with a small plate or a lid set on askew to allow gas to escape. Place in direct sun by day, shade at night. If you live on a balcony watched by pigeons, drape a clean cloth around the jar.

-

By day two, the brine should go pearly and begin to fizz. Taste daily. You’re aiming for a snap that is crisp yet forgiving, a sourness that rings like a cymbal without shattering your palate, and garlic that has gone from raw bite to sweet, bassy warmth. For me in late June in Budapest, it’s ready at 48 to 72 hours.

-

When happy, remove the bread and leaves. Transfer cucumbers and brine to clean jars and refrigerate. They keep a week or two with their sprightly sparkle; after that, they grow more sour and soft, not wrong, just older.

Important notes from old kitchens:

- Crispness trick: If your cucumbers arrive a bit tired, soak them in cold water with a pinch of salt for an hour before starting. They will stand straighter.

- Gluten-free alternative: Instead of bread, stir a tablespoon of active rye sourdough starter into the brine, or add a few slices of boiled potato, which feed the bacteria without bread. The most beautiful batch I ever made on a sweltering Békés afternoon used a tablespoon of tart whey from homemade túró (farmer cheese) as a starter.

- Don’t fear the cloudiness. Crystal clear brine is for vinegar pickles. In fermenting cucumbers, haze is life.

Every family I know eats kovászos uborka with something different. My neighbor Judit sets fat, seed-dimpled halves next to rántott hús, the breaded cutlet whose fried crust loves acidity. The late-night version—after pálinka has made everyone philosophical—is a cucumber speared straight from the jar, brine running down the wrist, then a bite of fresh white bread that tastes like flotation.

Savanyú Káposzta: Cabbage Transformed, From Barrel to Winter Bowl

If cucumbers are summer’s flash, cabbage is winter’s engine. Hungarian sauerkraut is not the sour hammer of childhood nightmares; at its best, it is silky and energetic, with a breeze of apple and a lazy drift of cellar wood. In rural kitchens, whole heads of cabbage are fermented for töltött káposzta—stuffed cabbage—so that each leaf peels away pliant and tart. For daily use, households ferment shredded cabbage in barrels or ceramic crocks.

A method, learned from an elderly couple in Vecsés—famous nationwide for its cabbage and a yearly savanyúság festival:

- Select firm late-autumn heads, heavy for their size, the leaves tight and sweet. Cold nights concentrate sugars, and sugar feeds the ferment.

- Shred using a káposztagyalu, a wooden mandoline so large it looks like a sled. Long, fine shreds are the goal; you want cabbage that will tangle around the fork like a noodle.

- Salt at 2 percent of the weight. Massage until glossy, then pack into a clean crock in fists, pressing until brine rises from the cabbage itself. This expression of brine is a small miracle every time—the vegetable becomes its own sea.

- Between each layer, scatter black peppercorns, bay leaves, and a whisper of whole caraway seeds. Some families add a few slices of tart apple or quince, a trick that perfumes the ferment with something faintly floral.

- Weight with a scrubbed stone or a plate and a water-filled jar. Seal with a lid if your crock has a water moat; otherwise, drape with cloth. Let it ferment cool, around 18 degrees C, for a week or two, then move it to a colder cellar to slow-cure. Eat it crunchy young in korhelyleves, the hangover soup of New Year’s Day, or let it mellow for a month and plan a töltött káposzta weekend.

There is an essential sensory test for cabbage: grab a handful, squeeze. If you hear a soft squeak between your fingers, like footsteps on new snow, the salt has penetrated, and the microbes are singing.

Csalamádé and Vegyes Vágott: The Winter Salad Barrel

Csalamádé—the name says salad and cellar in one breath. It gathers what the garden gave and what the market stills sells when fog crawls low: cabbage, green tomatoes, banana peppers, almapaprika, carrots, onions. Some families do a vinegar brine; others, like the Szeged grandmother who taught me, ferment it. The fermented version is a polyrhythmic band of textures and aromas, each vegetable playing its own instrument.

A fermented csalamádé that has brightened many Januaries in my kitchen:

- 1 small head cabbage, shredded fine

- 500 g green tomatoes, sliced

- 4 banana peppers, seeded and sliced into rings

- 3 almapaprika, thickly sliced

- 2 carrots, julienned

- 1 large onion, thinly sliced

- 40 g salt for every 2 kg of vegetables (2 percent)

- Optional: a handful of sour cherry leaves, a few sprigs of dill, 6 peppercorns, 2 bay leaves

Toss the vegetables with salt, massage until the bowl gleams with brine. Pack tight into a crock, layering with leaves and spices. Press down until brine rises above the mass. Weight and cover. Ferment cool for 5 to 7 days, tasting daily. This ferment wins you with its contrast: the buttery hush of cabbage, the squeak-snap of green tomato, the citrus-like ting of banana pepper skin, the hush of onion turned sweet.

Serve as a side to pörkölt, the paprika stew that would otherwise stomp across the palate, or with disznótoros—platters of sausages and roasted meats laid out after winter pig slaughtering. When I first ate csalamádé with hurka, the grainy, spiced blood sausage, the sour stepped forward like a benevolent aunt and took the sausage’s arm.

The Vecsés Barrel and the Budapest Counter: Where to Taste and Learn

You can study fermentation in books, but in Hungary, you also learn it by eating. Two places I send every curious palate:

- Vecsés Savanyúság Festival: Held in September as the fields tip to gold. Look for long tables of cabbage variations: crunchy young krauts, long-fermented, quince-scented batches, pale-pink jars stained with beet. The air smells like dill and frying lángos.

- Nagyvásárcsarnok and Klauzál téri Vásárcsarnok in Budapest: At the savanyúság stalls, ask to taste. Vendors will slice kovászos in the moment; they’ll press small forks into your hand, let you compare clove-scented beets to peppercorn-studded carrots. They are generous with knowledge—how long they leave the bread on, whether they prefer sour cherry leaves or grape.

A note to travelers: The word for fermented pickles is often simply kovászos or savanyú, but feel free to ask. Hungarians love a pickle conversation. Watch how a grandmother examines a jar: she holds it near the nose for two breaths, turns it for cloudiness, presses a cucumber with the pad of her thumb, and listens—somehow, always listening.

How Hungarian Fermentation Differs From Its Neighbors

In Poland, ogórki małosolne—the lightly salted summer cucumber—feels like a cousin to kovászos uborka. In Germany, Kraut is often peppered with juniper and leans toward a cleaner, more assertive acidity. Russia’s kvashenaya kapusta can be extremely crunchy and salt-forward, sometimes with cranberries or carrot.

Hungary’s hallmarks:

- The Sun Factor: Kovászos uborka is almost always set in bright light, a nod to the belief that warmth and sun encourage the right microbes. Poles often tuck theirs in the shade. The solar warmth seems to amplify the cucumber’s effervescence in Hungary.

- The Bread Cap: While some Slavic recipes use a piece of bread to jumpstart a ferment, Hungary leans into this rye cap with evangelic zeal. It’s a symbol as much as a method. Breaking out the bread later, sitting warm and sour-smelling on the counter, is part of the rite.

- Leaf Lore: The use of horseradish leaves is particularly Hungarian. Sour cherry leaves are more popular here than in many neighboring traditions and lend a very specific, tea-like fragrance.

- Pepper Love: The sheer variety of peppers is unmatched. Almapaprika, cseresznyepaprika (cherry peppers), banana peppers—fermented or pickled—appear with everything. While vinegar is common for stuffed cherry peppers, brined versions exist and have a rounder, softer tang that coaxes the pepper’s fruitiness forward.

Tools of the Hungarian Pickling Trade

You can ferment with a jam jar and a stone, but a Hungarian pantry has its heroes:

- Uborkás üveg: Tall, clear jars designed with a shoulder that holds cucumber stacks upright, almost architectural.

- Fermentation crock with water moat: The burbling moat keeps oxygen out and aromas in, and it looks like something your great-grandmother would trust.

- Káposztagyalu: The cabbage sled that makes shreds like lace.

- Weights: Ceramic or glass. In older kitchens, it’s literally a river stone scrubbed and boiled, heavy with memory.

- Sieve and slotted spoon: For skimming any surface yeasts and lifting vegetables without bringing chaos.

- Spices drawer: Dill heads drying near the window; caraway in a corked jar; bay leaves like paper boats; peppercorns black and bright.

Sensory Map: What You Should See, Smell, and Hear

When I teach fermentation to cooks new to Hungarian methods, I ask them to build a sensory map:

- Eyes: Brine should cloud like early morning lake water. Cucumbers go a slightly olive green, then a calmer green-gold. Cabbage lightens from jade to pale straw. Bubbles cling to the jar walls; a slow elevator of gas lifts, pops, and repeats.

- Nose: Young ferments smell bready from yeast, then green-apple bright, then lactic. If you smell solvent, a sharpness that stings like nail polish, check your temperature and salt. If you smell mold (a basement gone wrong), inspect the surface and remove anything slimy or fuzzy.

- Touch: Cucumbers feel crisp with a whisper of give—think a firm peach rather than a raw carrot. Cabbage should squeak between molars. The brine slickness is a sign of pectin and life, not a reason to panic.

- Sound: You will hear fizz when you open a jar that has been minding its business. It’s a soft, courteous hiss, sometimes a burble if you’ve been generous with temperature.

Troubleshooting With Grandma’s Calm

Hungarian grandmothers do not panic. They skim. They adjust. They trust the nose.

- Soft cucumbers: Too warm, too little salt, or cucumbers past their prime. Next time, lower the temperature by moving the jar deeper into shade or ferment fewer hours. Use smaller cucumbers with prickly skins. Add extra grape or sour cherry leaves for tannins.

- Surface film: A thin, matte, cream-colored layer that looks like chalky scum is often harmless kahm yeast. Skim and continue. If you see furry, colorful molds (blue, black, fuzzy green), remove all affected materials and consider discarding; trust your judgment.

- Hollow cucumbers: Under-salted brine or cucumbers with large, mature seeds. Select younger cukes. Slitting them adequately reduces hollow centers.

- Overly sour kraut, squeaky-sharp: Fermented too long or too warm. Blend with a younger batch. When cooking, soften with a spoonful of lard or a diced apple.

- Brine not rising in cabbage: You didn’t massage enough or the cabbage was dry. Make a 2 percent salt brine and top up until the cabbage is submerged. Weight more firmly.

A tip that saved a batch for me once in Szolnok: If the cucumber jar teeters toward too tangy, pull the cucumbers, rinse lightly, and set them in fresh, lightly salted cold water in the fridge. It tames the acidity without killing the sparkle.

How-To: A Starter-Free, Bread-Free Kovászos for Modern Kitchens

For cooks who need a predictable ferment without bread—and without a crock—here’s a faithful adaptation:

- Pack cucumbers as for classic kovászos with dill, garlic, and leaves into a 2-liter glass jar.

- Mix a 2 percent brine and stir in 1 tablespoon of active rye sourdough starter or 1 tablespoon of whey. If neither is available, use a few slices of boiled potato.

- Fill the jar to cover vegetables, leaving an inch of headspace. Fit with an airlock lid or a silicone waterless airlock.

- Ferment at 24 C for 2 days. Taste. When just about right, transfer to the fridge for 24 more hours, which evens out flavors.

- This method gives a consistent sparkle and crispness. The subtle bread note changes to a gentle bakery aroma without crumbs.

Serve with túrós csusza, the bacon and cottage cheese pasta, whose creamy heft begs for a bright, crunchy partner.

Pairing Pickles With Hungarian Plates: A Love Story

Fermented pickles don’t just sit demure on the side; they talk back to the main dish. A few pairings that make me happy:

- Kovászos uborka with rántott hús: The cutlet’s robe of crumbs meets cucumber’s effervescence. Add a wedge of lemon and a pinch of flaky salt to the plate.

- Savanyú káposzta with töltött káposzta: Tart on tart, but the textures are the key—silky cooked cabbage rolls, crisp raw kraut. The latter fluffs the palate between bites.

- Csalamádé with füstölt kolbász and brown bread: The sausage’s smoke sidles up to the salad’s brightness. A mouthful of beer and you’ve got a triangle of joy.

- Fermented almapaprika with babgulyás, hearty bean goulash: The pepper’s fruit-sour bite cuts bean starch in a way that tastes like a window opening.

- Pickled beets (cékla, sometimes lightly fermented) with abált szalonna, the poached, paprika-rubbed pork belly: Purple on porcelain; sweet earth against pork’s silken fat. A swipe of strong mustard, and the table goes quiet for a moment.

A Calendar of Sour: When to Ferment What in Hungary

- May to July: Cucumbers at their crunchiest. Make kovászos uborka week after week; as one jar is eaten, another goes out to sunbath.

- Late August: Mix jars of vegyes vágott when peppers and tomatoes still have heat in them but nights hint at wool. Start thinking about csalamádé for winter.

- September to November: Cabbage goes into crocks. If you can, source from growers near Vecsés, where cabbage tastes like it remembers the old floodplains.

- December to February: Eat from the pantry. Korhelyleves on New Year’s Day, with kraut that smells like an Alpine cabin warmed by a stove. Cherry pepper rings with fatty pork roasts. Beets to stain winter plates with the color of royal cloaks.

The pantry is a time capsule, and fermentation lets you open it slowly. Each jar is a different hour of the year.

Safety, Salt, and Good Sense

Fermentation is forgiving but not careless.

- Use clean, not sterile, equipment. Boiling hot water rinse for jars and weights suffices.

- Filtered or well water is best; chlorine can slow your microbial cast.

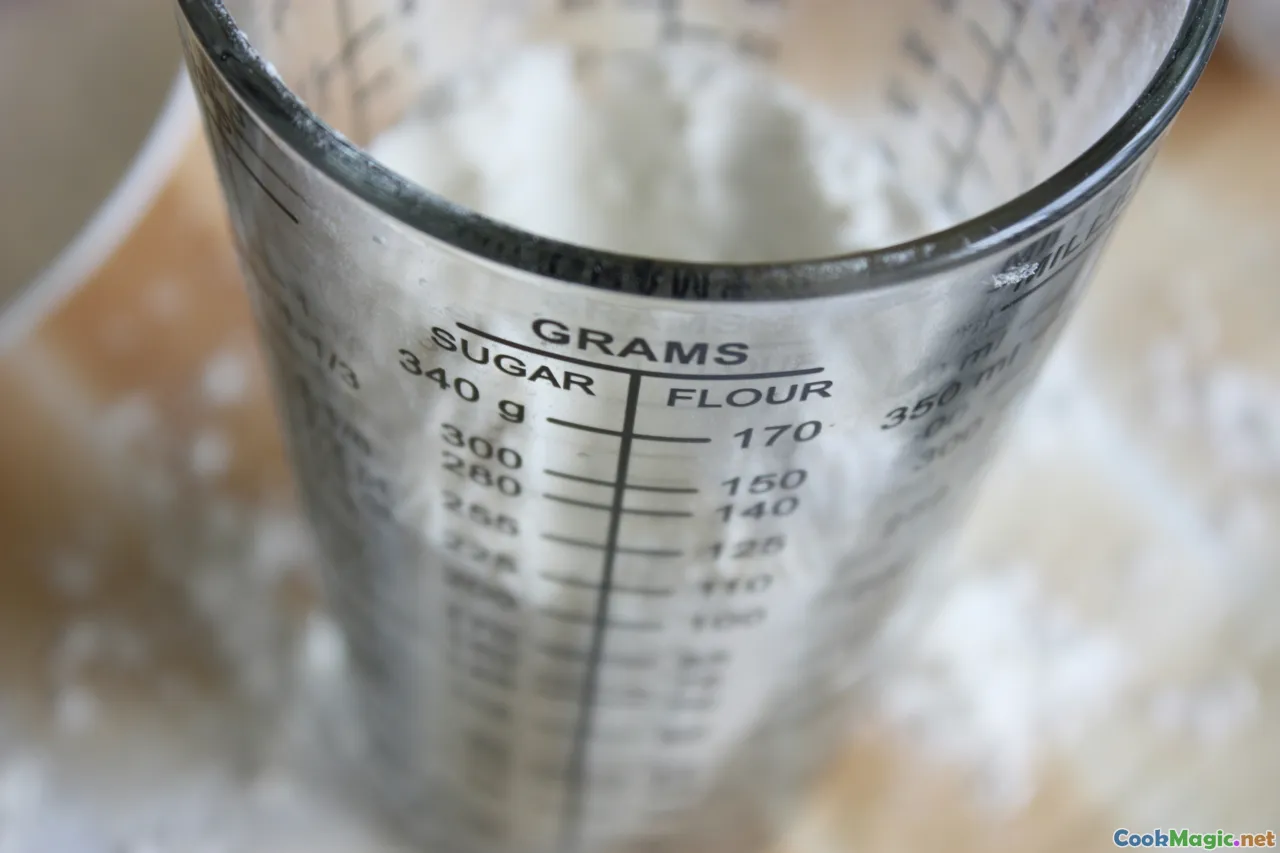

- Weigh salt when possible. A digital scale makes repeatable deliciousness. For cucumber brines, aim for 2 to 2.5 percent by weight; for cabbage, 2 percent of cabbage weight. Pepper and mixed ferments land around 2 percent as well.

- If you own a pH meter or strips, you want to see numbers under about 4.0 by day three or four for cucumbers, slower for cooler ferments. But your senses—sour scent, active bubbling—guide you well.

- When in doubt, throw it out. A Hungarian grandmother will scold you for waste, but not for caution.

Field Notes From a Day of Fermenting in the Alföld

One August, on the Great Hungarian Plain in a low farmhouse painted egg-yolk yellow, I spent a day in a kitchen that seemed built from steam. The mother, Erzsébet, brought out a bowl of cucumbers so fresh their tiny spines were still pale and tender. We trimmed and slit and packed; her daughter tucked dill heads in as if bedding down children for a nap. The father came in from the yard with horseradish leaves still breathing, shook off dust, and wiped them once with a damp towel.

We wrapped the rye heel in gauze—“so the crumbs don’t stick to the cucumbers,” Erzsébet said—and laid it on top. The jar looked like a small aquarium, everything green inside swimming in promise. She set it on the window, and the heat of the afternoon made it sweat.

That evening we ate csirkepaprikás and nokedli, little dumplings that resemble clouds. Erzsébet placed last year’s csalamádé on the table: the cabbage was so fine it tangled like hair. The green tomatoes had a squeak that sang in my jaw. And the smell of the new cucumbers, not yet ready, not yet sour, drifted behind us—clean, like a stone rinsed in a river.

Over pálinka, we argued about leaves: sour cherry versus grape. Erzsébet shrugged. “Cherry leaves for perfume,” she said. “Grape for strength.” The father lifted his glass. “Both,” he said, and we clinked.

Why These Flavors Belong Beside Paprika and Pork

Hungarian cuisine loves deep, red warmth—paprika carried in oil, slow-simmered onions sweet as jam, pork that slumps when you look at it. But a table is a conversation, and fermentation gives the food its questions, not just its answers. Lactic acid is rounder and more insinuating than vinegar. It lifts heavy stews without grabbing the throat. It refreshes the tongue between bites of fat and smoke.

Think of a spoon of pörkölt, hot and sticky with paprika. Now think of a forkful of kraut after that, how your mouth becomes a clean room, how you can taste the paprika again, new. Think of salted goose leg or csülök, the gelatinous shank, shivering on a plate, and then the sparkle of a cucumber that snaps like a joke told at the perfect moment. This is what fermentation gives: tempo and texture, a second chance to notice everything.

Your First Hungarian Ferment: A Simple Plan for the Week Ahead

- Day 1: Buy small cucumbers, a bunch of dill with heads, and a bundle of grape or sour cherry leaves. Grab good rye bread. Clean a 3-liter jar.

- Day 2: Pack and brine. Set the jar on a sunny sill. Watch for the first lace of bubbles by evening.

- Day 3: Tilt, taste, grin. Adjust the jar’s time in the sun as needed—if it’s racing, give it shade.

- Day 4: Harvest. Move to the fridge. Set the empty jar on the counter and feel the phantom weight of your next batch. Once you begin, the jars multiply.

- Next weekend: Visit a farmers’ market. Buy a cabbage heavy with promise. Shred it with respect. Salt and squeeze until the squeak sings.

If you stick to this plan, by this time next week your kitchen will smell a little like a Vecsés cellar, a little like a bakery, and your friends will begin to arrive mysteriously around mealtimes.

Practical Add-Ons: Beet-Tinted Kraut and Cabbage-Stuffed Cherry Peppers

- Beet-kissed savanyú káposzta: Shred a raw red beet into your cabbage before packing. The brine will blush a royal pink that looks like superstition in a jar. The beet’s sweetness rounds the acidity; it pairs beautifully with cold roasted pork.

- Cseresznyepaprika stuffed with fermented cabbage: Core cherry peppers with a small knife, leaving them like tiny red bowls. Blanch quickly to soften walls, just 30 seconds. Pack with young fermented cabbage mixed with a whisper of caraway. Ferment the stuffed peppers under a light 2 percent brine for 3 to 4 days at 18–20 C. The result is a single bite that tastes like a holiday—crunch, sour, pepper warmth, and the distant hymn of caraway.

The Taste of Memory: Why Fermentation Endures Here

Hungary sits at a crossroads and knows how to keep what matters. Fermentation is a ledger of seasons and a grammar of thrift. It is also a scent that binds memory to place. I can tell you that lactic acid oscillates on the palate around sharpness and softness, but what you will remember is this:

- The clouding of brine on a hot day is the same in Budapest 2025 as it was in a village kitchen in 1925.

- The crack when a fresh cucumber breaks is a sound that wakes children from naps at the table.

- The laugh that follows a too-sour bite is the laugh that keeps families in orbit around each other, even when everything else changes.

I keep a small jar of dill seeds gathered from a garden near Szeged. Every time I open it, it smells like the high hum of July. That humming lays over the pork and paprika of the table like a thin silk scarf. This is what fermentation in Hungarian pickled vegetables gives: a way to wear summer in winter, a way to soften winter in summer, a way to feed hunger and memory at once.

And so I return, each year, to the market stalls where brine glows in glass and jars are turned like hourglasses. I ask the same questions and get new answers: grape or cherry leaves this year, rye heel or sourdough starter, balcony sun or kitchen shade. Then I go home, pack a jar, and wait for the first breath from the brine—the same soft exhale my Hungarian friends call life beginning.