Decoding the Classic New England Clam Chowder

41 min read Explore the origins, essential ingredients, and technique behind New England clam chowder—balancing brine, cream, and smoke—plus shopping tips, regional nuances, and cook’s secrets for deeply flavorful bowls. October 10, 2025 18:08

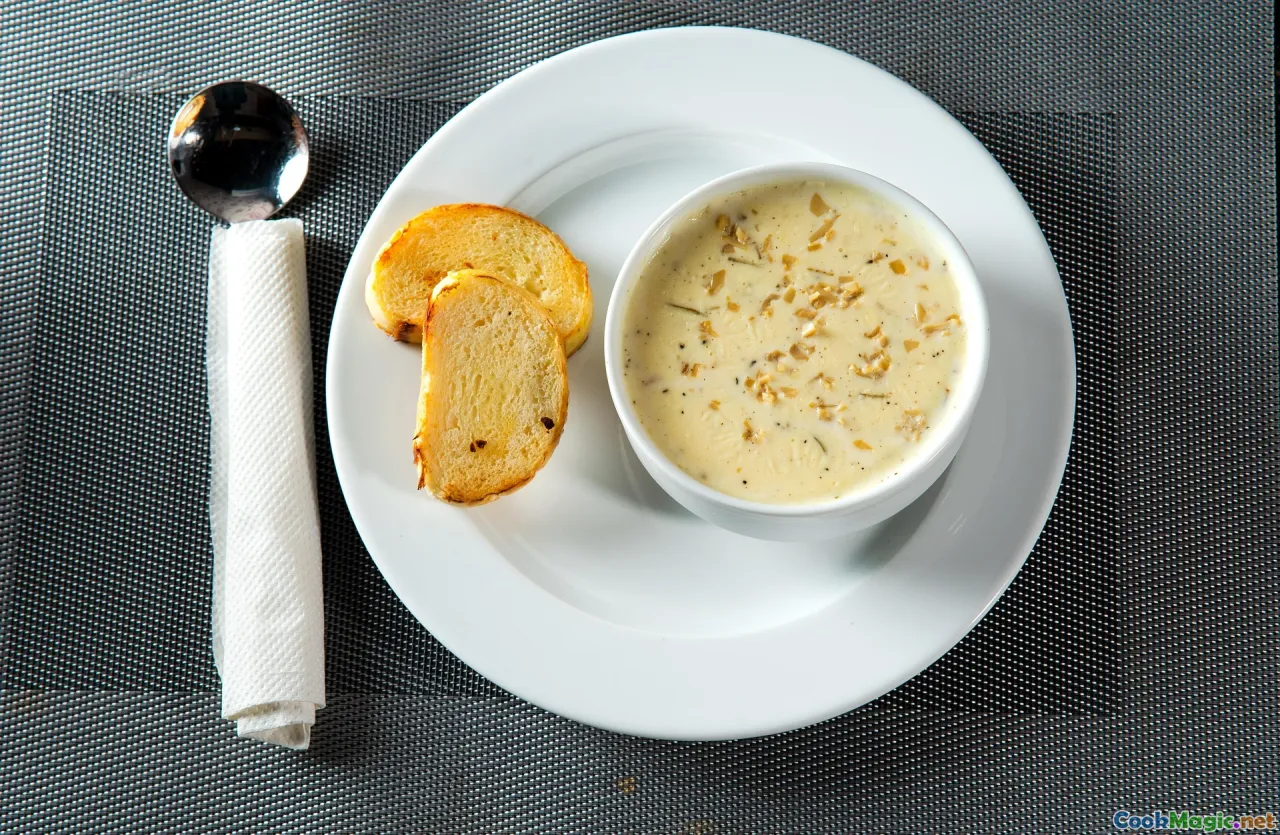

The first steam you smell is salt and sweet cream, a breath of the Atlantic curling up from a white bowl. Somewhere there’s a gull arguing with the wind, a dock bell rasping in the gray. You lift the spoon and it’s heavy—the kind of thick that clings just long enough to promise warmth, then slides back, rippling around a chunk of potato and a pink edge of salt pork. The clams are the voice in the chorus: briny, mineral, a little wild. It’s New England clam chowder, and when it’s right, it tastes like a shoreline memory you can drink.

I’ve chased this bowl from Boston’s wharf counters to a barn-red diner in Camden; I once sprinted down the ferry ramp at Vineyard Haven to make last call at The Black Dog for a cup of chowder to cradle through the crossing. And I’ve made more batches than I can count: breaking a dairy base on a Friday night in February, finishing a beautiful pot with a scatter of chives in July while somebody on the porch shucked littlenecks with a church key. This, then, is a decoded map of the classic—where it came from, why it works, and exactly how to make it so that the first spoon of steam tastes like ocean and home.

What Makes New England Clam Chowder "New England"?

If you lined up the chowders of America like a flag parade, New England’s would be the snowy standard-bearer: a pale, creamy broth; tender potatoes; soft onion; a savory hum of salt pork or bacon; and—most crucial—clams that taste like tide and sun on a dock. Unlike its scarlet cousin from Manhattan (tomato-based) or the clear broths of Rhode Island, the New England style is dairy-rich. The whiteness is its identity, but not its essence. The essence is restraint.

At the core of a classic bowl are short, trustworthy ingredients:

- Quahog clams (hard-shell, often chopped) or their smaller cousins.

- Pork fat—traditionally salt pork, sometimes bacon.

- Onion, and sometimes a whisper of celery.

- Potatoes, cut to match the clams so every spoonful eats evenly.

- Dairy—milk and/or cream.

- A thickener, if you dare (a light flour roux or a few crushed crackers; purists debate).

- Bay leaf, thyme, black pepper. Occasionally a wink of nutmeg.

What New England clam chowder is not: it isn’t loaded with carrots and peppers, it isn’t aggressively garlicked, and it doesn’t chase novelty. It’s a working soup from a working coast—born in hooks and tides and cold mornings, refined in inn kitchens from Providence to Bar Harbor. The flavors are specific but quiet, the kind that reward leaning in.

A Short, Steamy History in a Bowl

Chowder came across the Atlantic in the 18th century as a sailor’s stew—chunks of fish layered with ship’s biscuit and salted pork, simmered until the biscuit softened into the broth. The word itself brushes shoulders with French (chaudière, the pot), English, and Breton roots. In New England, where the coastline offers both fish and fat-bellied hard-shell clams, the dish settled into its clam incarnation.

By the 19th century, American cookbooks were printing “chowder” with cod or clams, often thickened with a few crushed crackers, enriched with milk or cream where available. Milk was a luxury in seafaring days, but by the time Boston and Portland were bustling ports with dairy infrastructure pushing into the cities, adding milk was both practical and pleasurable. Post–Civil War urbanization and the rise of oyster houses made chowder an emblematic city dish as much as a coastal one. One of the country’s oldest restaurants, Boston’s Union Oyster House, has served clam chowder for generations, the steam rising in the same amber light that once warmed Daniel Webster.

During the 20th century, the bowl got both famous and contested. Manhattan’s tomato-driven version—likely influenced by Portuguese and Italian immigrants—incited a comic legislative kerfuffle in Maine during the 1930s, when a state representative proposed banning tomatoes from chowder by law. It wasn’t enforced; the point was pride. In Rhode Island, where clear clam broths are a thing of devotion, dairy is set aside, the ocean speaking even more plainly. And then there’s New England proper: Legal Sea Foods made a political splash by serving its clam chowder at multiple presidential inaugurations, starting in 1981. The style had cemented itself as an emblem of the region—the culinary equal of a lighthouse.

Anatomy of a Classic: Ingredient-by-Ingredient Analysis

-

Clams: The heart. In New England, “quahog” is a clam and a cultural anchor. Littlenecks (small) are sweet and tender, great for raw plates. Cherrystones and topnecks are larger, firmer, and excellent for chowder. Big “chowder clams”—the oldest quahogs—carry the deepest flavor but need dicing. Freshness is non-negotiable: shells that snap closed when tapped, a clean brine smell like wet granite and tide.

-

Pork: Salt pork is cured backfat, old-school and nearly waterless, rendering into translucent cubes that taste like concentrated bacon without smoke. Bacon, meanwhile, brings smoke and a different brand of salt. Either can be correct; the choice writes your bowl’s accent.

-

Aromatics: Yellow onion is your engine. Celery is divisive. Some coastal cooks add a stalk or two for lift; others, especially purists in Maine, skip it to maintain a simple profile. Bay leaf is common; thyme is a near-whisper.

-

Potatoes: Waxy or all-purpose potatoes (Yukon Gold) hold their shape and lend a buttery texture. Russets offer starch that naturally thickens the broth but can give a mealy bite if overcooked. Cut them to the same size as your clams for textural symmetry.

-

Dairy: Whole milk for a clean, pourable broth; light cream for richness; heavy cream for luxury. Many coastal diners hit a sweet spot at 2 parts milk to 1 part light cream. The dairy should enrich but not bury the clam liquor.

-

Thickener: A tablespoon or two of flour cooked in fat; or a few common crackers crumbled in; or none at all. The best chowders can stand without a starchy crutch if the potato and dairy balance is right. Over-thickening is the enemy of clarity.

-

Seasoning: Freshly ground black pepper belongs. Salt approaches stealthily through pork, brine, and clam liquor. Taste late and often.

-

Finish: Chives or parsley brighten the rim. A pat of butter at the end can tidy texture and scent.

Clams: Digging into Provenance and Practice

If you’ve ever raked for clams in cold water, you know the thrill of your fingers meeting that smooth shell in a silt bed, the little tug between you and the tide. Quahogs are native to the East Coast, abundant in Narragansett Bay, Cape Cod, and up the Maine coast. On menus you’ll see sizes labeled by colloquial names. From smallest to largest: countnecks (rarest, tiny), littlenecks, topnecks, cherrystones, and finally chowder clams. The bigger the clam, the tougher the muscle—but the stronger the flavor. For chowder, I often steam a mix: cherrystones for texture and brine, a few big chowder clams for depth.

Buying tips:

- Ask your fishmonger for day-boat clams kept cold and dry. Clams should be heavy for their size and smell like clean tidewater.

- Tap any open shells; they should close. Reject cracked shells or anyone that refuses to wake up.

- Keep clams on ice in the fridge, covered with a damp towel—never submerged in fresh water, which kills them.

Purging sand is essential. Soak clams in a bowl of cold, heavily salted water (about sea salinity) for 20–30 minutes—better yet, layer them on a rack over the bowl so the grit falls away. Some cooks add a handful of cornmeal to the water; in my experience, a good purge and a careful strain of the steaming liquor does more good than cornmeal myths.

To open, steam: Add a half inch of water or dry white wine to a wide pot, lid on, high heat. When the first clatter of shells turns to a hushed rattling, check and pull clams as they open so the tender ones don’t overcook. Save every drop of juice—strain it through a coffee filter or a double layer of cheesecloth to catch the last sand. That liquor is your chowder’s backbone.

The Stock and the Sea: Broth Science

The best chowder tastes like someone washed cream through a tide pool. That’s the alchemy of balancing dairy fat with saline clam liquor and the savory notes from rendered pork. It’s delicate. Too much cream and you drown the ocean. Not enough and the bowl tastes thin, as if you stirred hot milk into potatoes.

Here’s the science in simple terms:

- Fat carries aroma. Butterfat in milk and cream spreads the perfume of clams, onions, and pork up to your nose. Without fat, chowder can taste flat even if it’s salty.

- Starch shapes body. Potato starch and a small amount of flour suspend tiny droplets of fat and trap aromatic compounds. That’s why chowder “blooms” on day two.

- Heat matters. High heat can break milk proteins; they denature and curdle in briny environments. Gentle heat keeps the emulsion smooth.

I build the broth in layers: render pork, sweat onions in that fat, deglaze with strained clam liquor, simmer potatoes in a mix of liquor and water or stock until tender, then—and only then—add dairy. If I want a touch more body, I’ll stir flour into the pork fat before the onions, creating a pale roux that toasts for a minute to lose its raw edge. The dairy goes in off the boil, heat lowered to just at a tremble, because nothing ruins a pot like splitting the milk.

Potatoes, Onions, and the Quiet Architecture of Texture

Texture is the soul of chowder—soft but not mush, thick but not paste, a chew that yields without a fight. Achieving that is less about a complicated trick than a series of small, disciplined decisions.

- Dice size: I match the potato cube to the chew of chopped clams, roughly 1/2 inch. Too small and they vanish; too large and they dominate.

- Potato choice: Yukon Golds give the cleanest, creamiest body without disintegrating. If I want the bowl to be a shade thicker without flour, I might go half Yukon, half russet.

- Onion technique: Sweat, don’t brown. Colorless onions keep the broth white and sweet; browning will drag in caramel notes that fight the sea.

- Timing: Clams cook fast. If you add chopped meat early, it tightens and goes rubbery. Fold them in with the dairy at the end, just long enough to warm and turn opaque again.

I learned one trick from a Cape Cod cook who’d been making chowder long enough to remember Crown Pilot Crackers on every shelf: hold back a cup of cooked potato, mash it lightly, then whisk it into the pot with the dairy to nudge body without flour. It’s invisible, natural, and allows the chowder to thicken gently as it stands.

Technique: A Step-by-Step How-To That Honors Tradition

What follows isn’t just a recipe; it’s a choreography of steam and scent to give you a classic bowl every time.

- Steam and chop the clams.

- Scrub 4 pounds of hard-shell clams (cherrystones/chowder clams) under cold water. Purge them for 20–30 minutes in salted water.

- In a wide pot, add 1/2 cup water or dry white wine. Bring to a boil. Add clams, cover, and steam until open, 5–8 minutes, pulling clams as they pop.

- Strain the clam liquor through a fine filter to remove grit; you should have 2–3 cups. Shell the clams, discarding the bellies if you prefer a cleaner flavor (traditionalists keep them), and chop the meat into 1/2-inch pieces.

- Render pork and sweat aromatics.

- Dice 4 ounces salt pork (or thick-cut bacon). In a heavy pot, cook over medium heat until the fat renders and the bits turn golden and translucent, 8–10 minutes. Don’t rush—the slow melt is flavor.

- If using flour, stir in 2 tablespoons; cook 1–2 minutes to make a pale roux.

- Add 1 medium yellow onion (small dice) and optionally 1 small rib celery (small dice). Sweat until onion is softened and glossy, 6–8 minutes, without browning.

- Build the broth.

- Add 1 bay leaf, a few sprigs of thyme, and 2 cups strained clam liquor. If your liquor is very salty, cut it with 1 cup water or light fish stock. Scrape the pan bottom to release any fond.

- Stir in 1 1/2 pounds Yukon Gold potatoes (1/2-inch dice). Simmer gently until the potatoes are just tender but not falling apart, about 12–15 minutes. Taste and adjust salt; remember the dairy is coming.

- Enrich with dairy.

- Reduce heat to low. Add 2 cups whole milk and 1 cup light cream (or 1 1/2 cups milk + 1 1/2 cups half-and-half). Do not let the pot boil once dairy is in.

- If you held back a cup of cooked potato, mash it and whisk in now for a subtler thickness.

- Add clams and finish.

- Stir in the chopped clams and any juices that collected, plus 1 tablespoon unsalted butter. Warm gently 3–5 minutes until the clams are just heated through.

- Grind in black pepper. Remove bay and thyme stems. Taste for salt. A few drops of white wine vinegar or lemon can wake the edges if needed, but the acid should be imperceptible.

- Rest and serve.

- Let the chowder sit off heat for 10 minutes to marry. Ladle into warm bowls.

- Garnish with snipped chives or parsley and serve with oyster crackers or, if you can find them, New England common crackers warmed in a low oven.

Spoon cue: The perfect chowder coats the back of a spoon like satin; a traced line should hold briefly before it closes.

A Cook’s Debate: Milk vs Cream, Salt Pork vs Bacon, Flour or Not?

This bowl comes with opinions, and they’re worth testing in your own kitchen.

-

Milk vs Cream: Milk-first advocates argue for clarity—the clam liquor shines, the bowl feels drinkable, and you can finish a mug without fatigue. Cream-first cooks prefer a richer, lingering mouthfeel that reads more like a meal. My sweet spot is milk as the base, touched with light cream for length and gloss.

-

Salt Pork vs Bacon: Salt pork is classic and ironed-flat in flavor—salty, porky, unsmoked. It lets the clams lead. Bacon brings smoke; that smoke can feel modern, luxurious, and comfortingly familiar. I reach for salt pork when clams are pristine and briny; I might use applewood bacon in winter when the pork wants to whisper in the bowl.

-

Flour vs No Flour: Flour lends insurance against splitting and gives body, but too much makes paste. Some of my favorite bowls contain no flour at all, relying on potato starch and gentle heat. If you add flour, keep it to a spoon or two per quart of liquid, cooked in fat before the dairy enters.

-

Celery: A controversial celery dice can add green lift. The anti-celery camp calls it distracting. I use one slender rib at most, finely diced, mainly for aroma.

-

Herbs: Thyme is nearly universal; bay leaf is common. Dill is not traditional. Parsley or chives at the finish are fine. Nutmeg? A literal pinch, and only if you’re confident.

Benchmarks: Tasting Notes from Real Bowls Along the Coast

-

Union Oyster House, Boston, MA: A canonical pour—velvety but not cloying, with a light roux and a patient simmer. The pork note is subdued, letting the clam sweetness work. A bowl in that room feels like you’re eating with American history at the table.

-

Legal Sea Foods, multiple New England locations: Polished, consistent, the kind of chowder that hits the same mark whether you’re in Logan Airport or on the waterfront. They’ve ladled their chowder at multiple presidential inaugurations starting in 1981, a detail that sums up its steady, diplomatic charm. Medium-thick, clean onion, well-managed dairy.

-

The Black Pearl, Newport, RI: A legend among thick chowder fans. This is a spoon-stand-up bowl, lush and luscious, almost stew-like, packed with clams. It’s the exception that proves the rule: even thick, it reads as clam-first, not flour-first.

-

Captain Parker’s Pub, West Yarmouth, MA: Reigning champ of multiple Cape Cod chowder competitions, this one threads a balanced needle—creamy, pepper-fragrant, potato just shy of tender, with generous clam pieces that feel generous rather than stingy.

-

James Hook & Co., Boston, MA: A wharf-side cup you can carry down to watch the lobster boats. The chowder leans briny; you can taste the water. Bacon plays a backbeat, and the liquor is well-filtered, avoiding any sand squeak.

-

Jordan Pond House, Acadia National Park, ME: Famous for popovers, yes, but their chowder—served with those steam-filled pastries—is a study in pairing. The broth is milk-forward and gentle, a clear lens for the clams.

Tasting across bowls teaches you that there isn’t a single “correct” thickness or pork choice. Instead, there are principles: clarity of clam flavor, balanced salt, restraint in sweetness, and a texture that comforts without numbing.

Sourcing Guide: Where to Buy Clams and Dairy That Matter

-

Clams: Seek out reputable fishmongers who turn inventory fast. In Boston, James Hook & Co. and Red’s Best are reliable. On Cape Cod, look to markets in Chatham and Provincetown with day-boat signs. If you’re inland, ask for hard-shell clams shipped live in mesh bags; avoid vacuum-packed pre-chopped clams unless you trust the brand and provenance.

-

Dairy: Whole milk from a local dairy often carries more flavor and a rounder mouthfeel. In New England, brands like High Lawn Farm or Oakhurst are standards. If you can, avoid ultra-high-temperature processed (UHT) milks, which can behave oddly in soups.

-

Pork: For salt pork, look for firm, meaty blocks with minimal off-odors; keep it cold and dice fine. If opting for bacon, choose a relatively lightly smoked, thick-cut slab; heavy smoke can eclipse the clams.

-

Crackers: Westminster Bakers’ oyster crackers (from Vermont) are ubiquitous in New England and maintain a satisfying crunch. Common crackers—a big, bready cousin—are harder to find since Nabisco discontinued Crown Pilot Crackers; some regional bakeries make suitable stand-ins.

Variations With Integrity

Staying faithful to New England chowder doesn’t mean calcifying it. Variations worth your time keep the core intact while nudging an element.

-

Rhode Island Clear Chowder: Skip dairy entirely. Use double-strained clam liquor, water, and perhaps a touch of fish stock. Render pork, sweat onion and celery, add potatoes, then clams. Finish with black pepper and parsley. The bowl tastes like standing knee-deep with a rake.

-

Smoked Fish Accent: Stir in a small amount (3–4 ounces) of flaked hot-smoked whitefish at the end alongside the clams. This can create a bridge between salt pork and sea without shouting. Keep the dairy lighter.

-

Herb Butter Finish: Instead of raw herbs, blend softened butter with chopped chives and parsley, then whisk a spoonful into the pot off-heat. The fat carries herb aroma into every sip.

-

Cracker Roux: For a subtle thickener that adds grain nostalgia, crush a handful of oyster crackers and stir them into the hot broth before dairy. They dissolve and round the edges.

-

Corn? Proceed Carefully: Sweet corn shows up in modern bowls. It’s not traditional and easily steals the show. If you add it—say, in late August—use kernels shaved from one ear and simmer them briefly so they taste like sun, not sugar.

-

Bacon Lardons on Top: If you like bacon smoke but want to preserve a classic base, render bacon separately into lardons and crown the bowl at the table. That way, smoke is a garnish, not a driver.

Troubleshooting the Pot: Grit, Split, and Other Heartbreaks

-

Sandy Grit: This is the fast lane to an angry table. Purge clams properly; strain the liquor through a coffee filter. Don’t skip the filter—fine sand survives even a tight mesh.

-

Split Dairy: High heat and acid are culprits. Keep the flame low once the milk goes in. If deglazing with wine, cook it off before adding liquor. If you accidentally split, you can emulsify a little with an immersion blender, but the texture will be less silky.

-

Bland Bowl: Salt hides in pork and clam liquor. If your chowder tastes shy, it likely needs a touch more salt and pepper near the end. Another trick: a 1/4 teaspoon of fish sauce adds umami without revealing itself.

-

Gluey Texture: Too much flour or overcooked russets. Switch to Yukon Golds and scale back the roux. Resist hard boil; keep a sighing simmer.

-

Rubbery Clams: Overcooked. Always add chopped clams near the end, just to warm. If using canned clams, drain and reserve liquid; add meat for only a minute or two.

-

Too Thick: Thin with reserved clam liquor, milk, or a little hot water, one ladle at a time. Rebalance salt afterwards.

-

Too Thin: Simmer a few minutes to reduce, or whisk in mashed potato. Avoid dumping in raw flour late—it tastes chalky.

Pairings and Rituals: What to Serve With Chowder

-

Crackers: Oyster crackers are the classic floaters. Toast them briefly in a low oven with a smear of butter and black pepper for extra pop. If you’ve sourced common crackers, split and toast them—the jagged edge drinks broth like a sponge.

-

Bread: A New England brown bread—molasses-sweet, dense with rye and cornmeal—makes a hauntingly good partner. Thinly sliced rye, buttered, is sharp and grassy against cream.

-

Greens: A bitter salad (frisée, radicchio, cider vinaigrette) resets the palate.

-

Drinks: Beer loves chowder. A crisp pilsner cuts cream; a Kölsch or a clean pale ale works. Wine-wise, look to mineral whites: Muscadet, Chablis, or a lean Albariño. In deep winter, dry cider is perfect—the apple core flavor tucks neatly into pork and dairy.

-

The Popover Exception: Up in Acadia, chowder comes with popovers at Jordan Pond House; the combination is a small miracle. Steam-filled pastry, salt-laced broth—one warms the other.

-

Ritual: Chowder is a porch dinner on a foggy July evening, a thermos on a fishing pier in November, a paper cup under a tent at a chowder cook-off with the sound of gulls and a brass band. It’s a bowl that asks you to slow down.

Recipe: A Cookable, Tested Formula for 6 Bowls

Serves 6 generously

Ingredients

- 4 pounds hard-shell clams (cherrystones or a mix with a few chowder clams)

- 1/2 cup water or dry white wine

- 4 ounces salt pork (or thick-cut bacon), small dice

- 2 tablespoons all-purpose flour (optional)

- 3 tablespoons unsalted butter, divided (1 for finish, 2 if using bacon instead of salt pork)

- 1 medium yellow onion, small dice

- 1 small rib celery, small dice (optional)

- 1 bay leaf

- 2 sprigs thyme (or 1/2 teaspoon dried)

- 1 1/2 pounds Yukon Gold potatoes, peeled and cut into 1/2-inch cubes

- 2 cups whole milk

- 1 cup light cream (or half-and-half)

- Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

- Chopped chives or parsley, for garnish

- Oyster or common crackers, for serving

Method

-

Steam the clams: Scrub and purge clams. In a wide pot, add the water or wine; bring to a boil, add clams, cover, and steam until they open, 5–8 minutes. Lift opened clams as they pop to avoid overcooking. Strain the cooking liquid twice through a coffee filter or double cheesecloth. Chop clam meat into 1/2-inch pieces; set aside. You need 2 cups clam liquor; supplement with water if short.

-

Render pork: In a heavy soup pot over medium heat, cook the salt pork until the fat renders and the pieces are blond and glassy, 8–10 minutes. If using bacon, render until crisp; remove the bacon to use as garnish and leave 2 tablespoons fat in the pot, adding 2 tablespoons butter if needed to reach that amount of fat.

-

Build the base: Stir in the flour (if using) and cook 1–2 minutes. Add onion and celery; sweat until onion turns translucent and soft but not brown, 6–8 minutes. Add bay leaf and thyme.

-

Potatoes and liquor: Pour in 2 cups strained clam liquor plus 1 cup water. Bring to a gentle simmer, then add potatoes. Cook until potatoes are just tender, 12–15 minutes. Taste the broth. It should be pleasantly salty but not bracing.

-

Dairy and clams: Reduce heat to low. Add milk and light cream; bring just to the edge of a simmer—no boiling. Fold in the chopped clams and 1 tablespoon butter. Warm 3–5 minutes until clams are heated through. Grind in black pepper. Adjust salt.

-

Rest and serve: Remove bay and thyme stems. Let sit 10 minutes off heat to marry. Ladle into warmed bowls, garnish with chives or parsley, and serve with crackers. If you rendered bacon, crown each bowl with a few lardons.

Cook’s notes

- For a flourless thickness, reserve 1 cup of the cooked potatoes, mash lightly, and whisk into the dairy just before adding clams.

- If you prefer a clearer, looser broth, use all milk and skip the light cream.

- For a whisper of acid that brightens without shouting, add 1–2 teaspoons of clam juice or a drop of white wine vinegar right at the end.

Make-Ahead, Storage, and Reheating

Chowder deepens overnight; it also thickens as potato starch hydrates.

-

Make-Ahead: Cook the base through the potato stage earlier in the day; hold chilled. Reheat gently, add dairy and clams just before serving. This preserves clam tenderness and dairy gloss.

-

Storage: Refrigerate within two hours, in a covered container. Eat within 2–3 days. The flavors will bloom on day two; the texture will be thicker.

-

Reheating: Low and slow. Warm over low heat, stirring gently so the bottom doesn’t catch, and stop at the barest simmer. If the chowder tightened in the fridge, loosen with milk or a splash of water. Avoid microwaving, which can toughen clams.

-

Freezing: Not recommended. Dairy can split, and potatoes go grainy. If you must freeze, do so with the base only—no dairy or clams—and finish fresh later.

A Personal Tide Line: Memory, Place, and a Winter Cure

In a January nor’easter a few years ago, I made chowder by flashlight when the power surrendered. The house creaked, snow lashed the windows, and the dog stared at the gas flame like worship. I had a pint of shucked quahogs from a market in Gloucester, a piece of salt pork wrapped in butcher paper, onions, potatoes, milk sweeping the back of the fridge. We ate cross-legged on the kitchen floor, bowls in our hands, and the spoon was like a metronome steadying the room. The broth smelled like a harbor at low tide, cleaned by wind. It tasted like competence—like we knew how to feed ourselves when it counted.

New England clam chowder carries that feeling even on an ordinary night in June, with windows open and laundry snapping on the line. It is comfort without saccharine, a reminder that perfect cooking can be plain. Each bite invites quiet: to feel the tender give of potato, the spring of clam muscle, the warmth of milk, the little electric shock of pepper at the end. If you live far from the Atlantic, the right clams and care can still put the ocean in your kitchen. If you live near it, you already know there’s a particular kind of bliss in eating the sea while it listens outside.

So steam the clams. Strain the liquor. Render the pork and be patient with the onions. Keep the heat low once the milk arrives. Ladle and listen; the bowl will tell you when it’s right. It will smell like tide and butter and a long story. And when the steam clears your glasses, you’ll understand why this white soup has held a coastline together for more than a century: it is simple, honest, and, at its best, profoundly good.