Daily Meals of a Tahitian Fisher Family

43 min read Follow a Tahitian fisher family's daily table—from dawn catch to lagoon-side suppers—featuring poisson cru, breadfruit, and coconut-rich staples rooted in ocean rhythms and island tradition. October 03, 2025 15:08

The moon is just a fingernail when the outboard coughs to life in Tahiti Iti, and the lagoon lies as still as a bowl of blue glass. From the porch, you can smell both sea-brine and the sweet, green breath of banana leaves dripping with dew. A grandmother ties her pareu at the hip with the practiced flick of someone who grew up reading tides like a calendar. The children are awake despite the hour, rubbing sleep from their eyes, hands already reaching for coils of line and the wicker basket that will bring home ature, octopus, or whatever the reef is ready to give today. This is the daily meal plan of a Tahitian fisher family: not a menu so much as a pulse that matches the lagoon—savory, sun-shot, salt-kissed, and stubbornly generous.

The Rhythm of a Fisher Family’s Day

If you ride over the mountain spine of the island to Tautira or Teahupo’o—the villages that anchor Tahiti Iti—you’ll see the choreography that organizes meals before you hear a single pot clang. The father stands in the pirogue cradled by a mangrove-edged shore, hands quick as birds as he checks the knots on the handlines. The mother watches the tide’s angle through the pass, eyes flicking to a pale patch of sky breaking into gold. A young cousin straps on a mask; a teenage niece tests the spear rubber with a sharp tug, face already half in the water. Breakfast will depend on what swims near the reef this hour; lunch will be decided by what the market did not sell the day before; dinner—if it’s Sunday—will grow quietly underground in an ahima’a, the earth oven that hums like a buried drum.

Here, meals are not planned around a pantry list but around cycles: the moon, the swell, the wind that scours in between the islands and brings flying fish within reach. These cycles thread through the day in a pattern as predictable as it is improvisational:

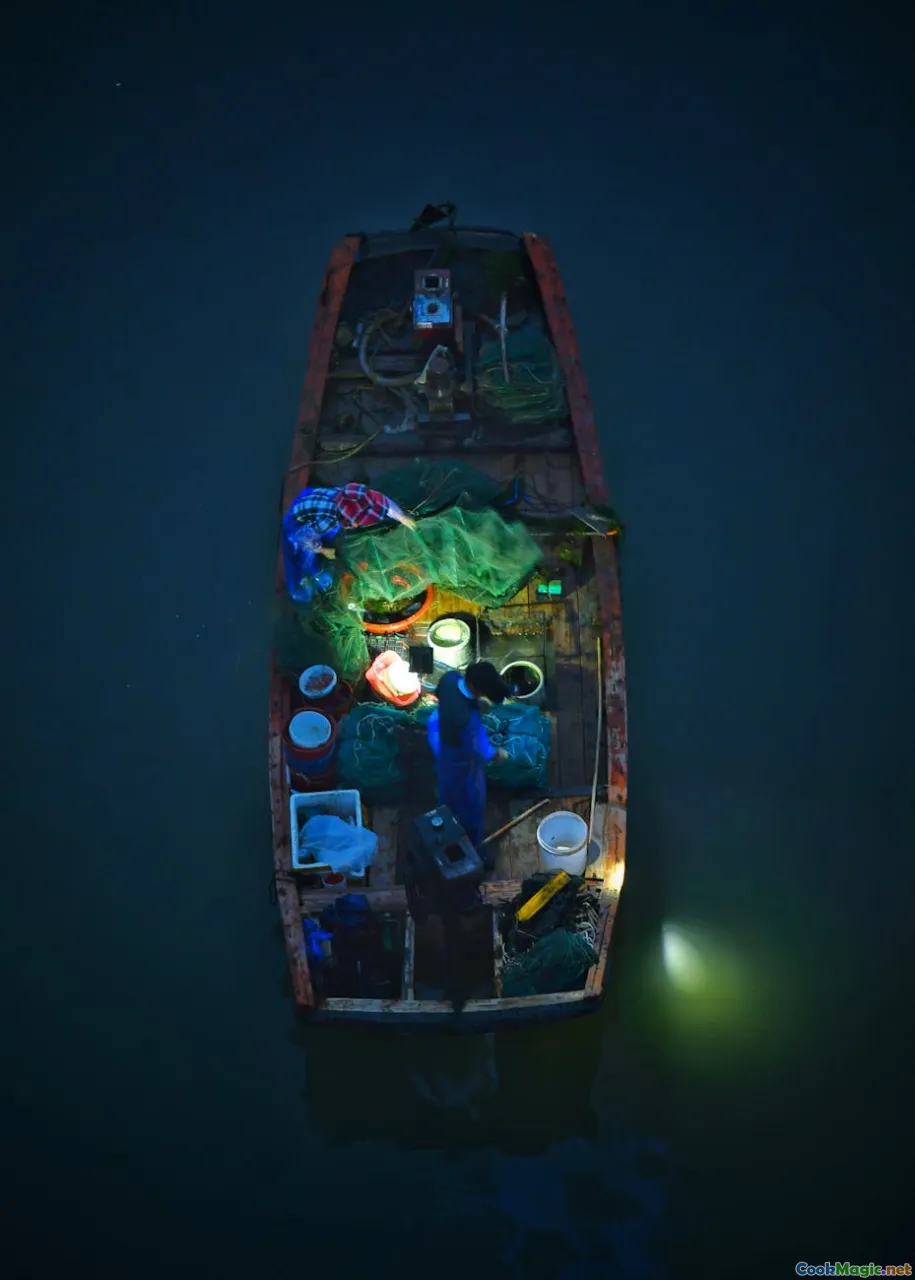

- Pre-dawn: Lines and nets, reef gleaning with torches or small LED lamps for octopus, urchins, and trochus shells.

- Dawn to morning: Quick fry of whatever came up shining—ature (mackerel scad) when the schools run, a goatfish nosed from sand, perhaps squid that inked the shallows.

- Midday: The raw, cold clarity of i’a ota (poisson cru), a salad that tastes like the lagoon tightened into one bite—lime-bright, coconut-cool, cucumber-crisp.

- Afternoon: Snacks from the coals—uru (breadfruit) blistered and smoky, or firi firi, the coconut donuts still whispering with oil.

- Evening: A pot of taro stewed soft in coconut milk, or fish souped with ginger and greens; on Sundays, an ahima’a that feeds a dozen.

The Lagoon Larder: Species, Seasons, and Stories

A Tahitian fisher family reads the lagoon the way a baker reads flour. Some species are old friends, others temperamental visitors. In the deep, beyond the reef pass where the water shifts from lapis to ink, there’s yellowfin for those with bigger boats and stronger backs. Close to shore, the daily bread swims in flickers of color:

- Parrotfish, their scales oil-slicked with greens and blues, strong-fleshed and sweet after a hot pan sear.

- Goatfish, with whiskers to stir sand—delicate and lean, best floured and kissed by butter.

- Unicornfish and surgeonfish, meaty and mild, good for curries or coconut.

- Ature, quicksilver schooling fish whose season sparks local fever—fried crisp, eaten whole with a squeeze of lime.

- Octopus (fe’e), the reef’s riddler, laid over hot coals until char blisters and the flesh turns silk.

There are the great pelagics too—mahi-mahi with its joyful green-yellow sides, wahoo with a racer’s body—brought in by uncles who chase the horizon. But for most fisher families, daily meals are reef-close, small-boat certain.

Tradition threads through this abundance. Elders still talk about rahui, the customary closures that rested certain parts of the lagoon, now being reawakened in places like Teahupo’o. They tell stories about learning to follow goatfish by the faint puffs of sand, about the time when breadfruit (uru) fell in such quantities that paths were perfumed with its sap and sweetness. They teach how to keep the lagoon’s gift whole: throw back the small; keep the egg-bearing; take only as the tide allows.

Breakfast: Salt on the Lips, Uru in the Pan

Breakfast is a mood, not a fixed dish, anchored by the sea’s temper. On a good day, ature thrash in the woven basket, air smelling of brine and metal. The father splashes the fish in a zinc bowl—scales flicker off like confetti—and the mother sprinkles sea salt and pounded garlic. A pan hisses; the fish hit the fat and curl, skin blistering to a lacquered crisp. Lime halves roll on the table like green marbles.

Breadfruit stands ready, starchy as a potato but with a perfume like freshly cut grass and warm almonds. One child feeds slatted pieces into a wire rack over a charcoal brazier; another rotates the fruit whole until its speckled green turns a leopard of black and brown, the skin beginning to peel like paper. When roasted breadfruit is torn open, it exhales a puff of steam with the smell of roasted chestnuts and a hint of coconut—an aroma that feels like a softened corner of the morning.

Alongside goes strong coffee, and if an aunt has been to the bakery truck early, a loaf of pain coco—coconut bread whose crumb is dense and slightly sweet, perfect for catching yolk from the morning’s egg or for satisfying a child who’s already halfway to the beach. Some mornings there are firi firi, long figure-eight donuts made with coconut milk. They taste like the best kind of carnival—crisp outside, tender inside, a bready sweetness kissed with sugar—and they are irresistible dipped briefly in strong, milky tea.

Breakfast in a fisher family is also a kitchen classroom. Tiny hands learn to pinch salt between fingers because a palmful is too much; a teenager practices a two-finger check for doneness on octopus—soft spring, not rubber. The talk floats between weather and chores, but always returns to flavor: more lime, more smoke, more salt—each mouth a barometer.

Midday Masterpiece: I’a Ota, the Lagoon’s Cold Flame

Noon demands something raw, bright, and cooling. I’a ota (poisson cru) is the edible shorthand for the Tahitian lagoon: a bowl of snap-fresh fish dressed in sunlight and shade. Each family has a method; this is the one I learned on a porch in Tautira, where the horizon is a silver line and the bowl is a wooden umete smoothed by years of coconut and lime.

How-to, the family way:

-

Choose the fish. The best i’a ota is cut from what the boat just brought in: tuna if they got lucky, trevally if not, or even a firm-fleshed parrotfish. It must smell like nothing but clean tide—no fishiness, just the ghost of salt.

-

Cube it clean. The knife flashes like a small mirror. Cubes are modest, just big enough to bite and feel the satiny resistance give way to velvet.

-

Chill with citrus. Limes roll into halves under a broad thumb; Tahitian limes are fragrant and floral, their juice headier than their looks suggest. The fish gets a splash, not a bath—five minutes to “cook” some outer edges while the center stays tender. In impatient households, this step takes three minutes. In the grandmother’s house, the decision is by eye: when the outer rim of each cube turns from translucent glow to a soft peach opacity.

-

Add the crunch. Cucumbers fractured into half-moons, tomato wedges that leak seeds like the inside of a pomegranate, sliced spring onion, a splash of sea water if you’re home already, or a pinch of coarse salt if you’re still on the dock.

-

Finish with coconut. Coconut milk thick as cream, made minutes ago by grating mature coconut and squeezing it through a cloth with a little warm water. It tempers acid with lushness. If the coconut was roasted slightly over coals before grating—a trick some families keep—the milk carries a smoke-memory that makes the whole bowl taste like a campfire near the sea.

The first bite is always a negotiation between elements: the lime snaps, the coconut swoons, the fish offers that clean oceanic sweetness at the center. It is temperature, too; the bowl has been waiting in the shade, the fish cool as lagoon shade, cucumber cold as a shouted laugh. Every ingredient remains itself but agrees to a truce that feels like a breeze across your tongue.

I’ve eaten versions flecked with grated ginger, or mango diced in during the heart of summer; in Moorea, I tasted one with a sparkle of crushed sea salt collected at low tide from a shallow rock pan. Purists raise an eyebrow at embellishment, but the point is pleasure, and the bowl returns empty either way.

Fafaru: The Fragrance of Home

If i’a ota is the lagoon’s bright laugh, fafaru is its love letter—bold, unmistakable, and fiercely personal. Fafaru is fish perfumed by a fermented brine called miti fafaru: seawater left to blossom with the help of crushed shrimp heads (chevrettes) or sometimes crab shells. The result smells like a dock at low tide and tastes like an embrace from something that remembers deeper waters. It’s a smell that, to outsiders, can be a dare; to the family whose jar sits on a shady shelf, it signals a house that knows where it is in the world.

How it’s made, respectfully:

-

Seawater is taken from beyond the breakers on a calm day, placed in a glass jar with the crushed heads of river shrimp or small lagoon shrimp and sometimes a piece of breadfruit leaf or ti leaf for good luck. The jar sits in a cool corner—never in the glaring sun—and the water slowly changes: a cloudiness rises, a roundness creeps into the scent.

-

A few days later (how many depends on the house and the nose), the brine is strained. It’s now a living thing—amber, faintly viscous, humming.

-

Thin slices of very fresh fish are dipped—briefly—in this brine just before eating. Dipped, not drowned. Fafaru is to perfume, not to soak.

On the plate, the fish glistens with a slight slick of miti fafaru, and you catch the smell even before you sit. It’s served with fe’i, the mountain plantains that steam to a pumpkin-orange sweetness, their color as bright as marigolds. There’s taro, too, and sometimes a bowl of miti hue, a fermented coconut cream sauce that is mildly tangy and brings the whole dish into balance. Taken together, the mouthful is wild and polite at once: ferment and fat, salt and starch, the softened bitterness of plantain and the gentle sour of coconut. I’ve seen a child at first recoil and then lean in again, curiosity wrestled by trust.

People talk about fafaru with an intimacy normally reserved for family. “This is my mother’s fafaru,” they’ll say, meaning the brine, the practice, the smell of a kitchen that has known three generations. The dish makes you present to place. It is a reminder that flavor is an inheritance.

Fires Underground: The Sunday Ahima’a

Sundays on Tahiti often begin with the faint thud of stones placed in a fire. The ahima’a—the earth oven—turns the yard into a kitchen the size of the sky. The men dig the shallow pit, line it with river stones, and set a fire so vigorous that the stones become white-hot. Nearby, banana leaves droop from moisture, ti leaves shine like waxed emeralds, and the yard fills with the buttery smell of grated coconut.

When the stones are ready, the layering begins:

- Stone and leaf: A mattress of ti leaves goes down to guard against scorching and to scent the food with their resinous, sweet-green perfume.

- Root and fruit: Breadfruit, taro, and fe’i are set whole or in large chunks, the heat starting to loosen their fibers immediately. You can hear fe’i hiss faintly as its sap meets hot stone.

- Meat and fish: Parcels of chicken with taro leaves (fafa) and coconut milk tucked in; pork rubbed with sea salt and crushed garlic; sometimes a whole fish stuffed with herbs and wrapped tight in banana leaves. The parcels are tied with strips of banana bark—a gift of the plant that gives rope as well as food.

- Shield and steam: More banana and ti leaves, then damp cloth or burlap sacks, then finally a cover of soil to seal in the heat.

Three hours later, the yard smells like a grove after rain: earthy, sweet, smoky. Digging open the ahima’a is a communal gasp—steam rises as if the ground itself is breathing. The breadfruit has gone from stoic to supple, the fe’i’s orange even brighter, the meat so tender the fibers sigh apart under a fork. Taro leaves have melted into a silk that clings to the tongue.

The Sunday table stretches long: cousins, aunties, neighbors whose boats share a mooring line. There’s laughter, and quiet too—a pause before a first bite, a silent grace. Desserts are simple and perfect. Po’e, the island pudding, sets with the shimmer of a lake—made from ripe banana or papaya beaten with arrowroot (pia) or, more commonly now, tapioca flour. It bakes in the ahima’a in leaf-wrapped slabs, then is cut and flooded with coconut cream. The texture is almost cheeky—bouncy, yielding—and the flavor lines up sunshine and orchard in one spoon.

Market Mornings in Papeete: Bridges Between Worlds

A fisher family lives by the lagoon, but the city’s market sets the rhythm for many urban meals. Marché de Papeete is a cathedral of color: plumes of bok choy and Chinese cabbage, pyramids of mango and starfruit, baskets of vanilla beans whose perfume lingers at the back of your throat. Upstairs, women sew tifaifai quilts from cloth bright as parrotfish; downstairs, fishmongers lay out silver bodies on crushed ice—beheading tuna with wet thunks, trimming fillets to pink perfection.

You see cuisine’s tides here: Sino-Tahitian stalls selling chow mein (chao men) tangled with pork and greens; baguettes crammed with tuna, mayo, and cucumber—a portable homage to i’a ota. Ma’a tinito—“Chinese food,” by name—simmers in stew pans: pork stewed in soy-salt with red kidney beans and Chinese cabbage, spooned over rice with a side of macaroni for those who measure comfort by multiples. Pick up a bag of ‘uru chips, thin as dragonfly wings, kissed with salt.

Nighttime moves the food to the roulottes, the food trucks clustered at Vai’ete Square. A family might go when the house is hot and the moon is full, ordering swordfish skewers lacquered with soy and honey, or poisson cru served in disposable bowls that still manage to feel ceremonial. The air is a Venn diagram: smoke, garlic, grilled pineapple, crepes crisping on hot plates. Every plate carries a conversation between Tahiti’s past and present, and each morsel slides back to the same home-cooked truths—salt, smoke, lime, coconut—just retold in neon.

Snack Plates and Small Hungers

Between meals is when the ocean does its quiet work in the body. After school, kids crash into the yard and hit the snacks, always “small” but never scant:

- Uru chips: Breadfruit sliced paper-thin, fried until their bubbles become freckles, sprinkled with sea salt. They snap with a clean crack; you can taste a whisper of green at the end.

- Coconut slivers: The day’s husked coconut is shaved into planks like white bark, chewed until your mouth feels glossed with coconut oil. Spritz with lime and a dust of chili for mischief.

- Vana roe: When the sea urchins are plentiful and the family has gleaned, a spoon of orange roe on a shard of fried breadfruit is like a small sun on your tongue.

- Banana with miti hue: A bowl of fermented coconut cream—mildly tangy, lush—over ripe banana rounds. It tastes like yogurt if yogurt remembered palm shade.

Snack plates are never fussy, but they carry the day’s map in them: what was gathered, what was left, what feels good after saltwater on your shoulders.

Rivers, Valleys, and the Taste of Fresh Water

Not all Tahitian meals are born of salt. The island’s valleys—Papenoo on Tahiti Nui, the deep folds above Tautira on Tahiti Iti—offer their own pantry. There are taro patches, their heart-shaped leaves floating like a hundred green kites tethered to water. There are bananas heavy as chandeliers, fe’i spearing up like orange torches from the hillside. And there are rivers that hide chevrettes, freshwater prawns, under rocks slick as jade.

A fisher family that knows the sea also knows when the river runs clear after rain, when chevrettes move in shadows. A basket of these prawns—quick to leap, quick to boil—becomes dinner sharp with ginger and garlic, or slips into coconut milk with tomatoes and handfuls of local spinach (fāfā, not the taro-leaf dish but the green itself) until the pot tastes ironic: a river with a memory of sea.

It’s a different smell, too. In the valley, heat rides up through ferns and wet earth; the kitchen holds the scent of damp bamboo, green bananas steaming. The palate shifts to welcome it: the iron of taro, the syrupy edge of very ripe papaya, the grassy snap of watercress pulled from a cool run.

Teaching Palates: How Children Learn the Lagoon

In a fisher family, you don’t so much “learn to cook” as learn to listen—to the sea, to your elders, to the changing pitch of oil in a pan. Children learn knife angles on breadfruit before fish; the breadfruit forgives clumsy fingers. They learn to gut goatfish in six motions, not seven; the last motion is rinsing under brackish water and checking for the clean, sweet smell that says it’s ready for the table.

Tastes are trained kindly but firmly. “Just one bite,” a grandmother says about fafaru, but the family knows that the first bite travels a long way; every child will someday recognize home by this smell. The funniest face gets the last piece of po’e; the bravest palate gets to salt the i’a ota. Praises are specific—“That is the right crunch on the cucumber”—because specificity is love here.

The kids also learn the economy of leftovers. Yesterday’s fried fish becomes today’s fish salad with grated carrot and soy; extra ‘uru reappears as mash crisped in a skillet, eaten with a thin slice of corned beef—the pantry compromise that has, for better or worse, braided itself into many island diets. Taste memory is a curriculum; it means knowing that the last piece of roasted breadfruit will be best at midnight, cold from the enamel bowl, eaten with fingers.

Three Workhorse Recipes for a Fisher Family

These aren’t restaurant plates; they’re everyday tools, learned by heart.

- I’a Ota (Poisson Cru), Classic Family Style

Ingredients:

- 500 g very fresh fish (tuna, trevally, parrotfish), cut into 1.5 cm cubes

- Juice of 4 Tahitian limes

- 1 small cucumber, halved, seeded, thinly sliced

- 2 medium tomatoes, cut into wedges

- 2 spring onions, thinly sliced

- 250 ml thick coconut milk (freshly pressed if possible)

- Coarse sea salt to taste

Method:

- In a wooden or glass bowl, toss the fish with half the lime juice and a pinch of salt. Let stand 3–5 minutes, just until the edges turn opaque.

- Add cucumber, tomatoes, spring onions, the remaining lime juice, and another pinch of salt. Toss lightly.

- Fold in coconut milk gently. Taste: you want lime’s spark first, then coconut’s hush, then the fish’s sweetness to rise at the end. Adjust salt. Serve immediately, cool as shade.

Cook’s note: If your limes are fierce, temper with one diced ripe mango or a teaspoon of grated ginger. If serving later, keep the fish chilled separately and combine just before eating.

- Uru Roasted Over Coals with Coconut Drizzle

Ingredients:

- 1 whole breadfruit (uru), green-ripe (press yields slightly)

- Banana or ti leaves (optional but traditional)

- 200 ml coconut milk

- Sea salt

Method:

- Roast the whole breadfruit over a charcoal grill or open flame, rotating every few minutes until the skin is charred black and the fruit feels soft under a prod (25–40 minutes depending on size).

- Split open; peel off the charred skin. Remove the core. Tear or slice the flesh.

- Warm coconut milk with a pinch of salt; pour over the hot breadfruit. Eat with fingers. The breadfruit’s nutty sweetness blooms against the salted coconut in a way that is both humble and royal.

Cook’s note: For a smoky twist, roast coconut shavings lightly and scatter on top. Uru loves smoke as much as it loves salt.

- Banana Po’e with Coconut Cream

Ingredients:

- 6 very ripe bananas

- 150 g tapioca starch (or traditional arrowroot/pia if available)

- 1 vanilla bean or 1 tsp vanilla extract

- 300 ml coconut milk

- 2 tbsp sugar (optional; ripe bananas are often sweet enough)

Method:

- Mash bananas to a smooth puree; stir in tapioca starch and vanilla. The mixture should be pourable but thick.

- Pour into a banana leaf-lined baking dish (or a buttered dish). Bake at 180°C for 30–40 minutes until set and slightly translucent.

- Cool slightly; cut into squares. Warm coconut milk with a whisper of salt and pour generously over the squares. Eat while barely warm, when the coconut perfumes the air and the po’e jiggles like a small, happy secret.

Nets, Knots, and Night Lights: Techniques That Feed the Table

Culinary stories are also stories of tools. Handlining—wrapping nylon around a small wooden winder, baiting with shrimp or squid, thumb and forefinger feeling vibrations through line—teaches attention you can taste later in fillets trimmed without waste. Spearfishing at night with waterproof lamps is the art of patience and breath; the world goes to grayscale, and parrotfish sleep in the coral’s crooks like bright pillows dulled by moonlight. You exhale slowly, fin like a thought, and when the spear releases, dinner becomes inevitable.

Nets are an elder’s archive. Gill nets are set at the pass when ature run, floats bobbing like a string of bright buoys sketching where dinner will come ashore. Children learn the structure of mesh the same way they learn to weave a palm frond: over, under, over. A well-mended net is love measured in hours of quiet, the kind of daily work that disappears by success; a torn net is hunger whistling.

And there is gleaning—the art of reading low tide. The reef offers vana (urchin), turban shells, little sea cucumbers, sometimes an octopus whose footprint—an odd rearrangement of shells and sand—betrays its home. A gleaned meal tastes like investigation and reward, a plateful of small things treated with big respect: a few plucked urchin tongues on a spoon, a sauté of chopped shells with garlic and ti leaf, eaten with rice and the last of yesterday’s roast fish.

The Old Rules Made New: Rahui and Respect

Ask why the fish tastes clean here, and someone will eventually say rahui. The old term speaks to a rotating rest for places or species—closures that were more prayer than policy and are now becoming both. In parts of Tahiti Iti, communities have re-established rahui zones, marked sometimes by carved posts or signs. They police themselves with pride and affection. It’s not nostalgia; it’s a practical memory. Fish return when the water is quiet. Coral breathes easier when fins and spears step back.

In the kitchen, rahui looks like choice. A fisher family decides to stew more greens when the parrotfish seem small this season, to swap goatfish for ature because the schools are running hard and bright. Kids learn it as muscle memory: that throwing back a juvenile isn’t generosity but discipline, that leaving urchin shells whole helps seed the reef, that breadfruit trees get cleared beneath to breathe but not cut back when heavy—the next storm will prune them.

A Night in Tautira: A Personal Table

I remember a night in Tautira like a film I can touch. The yard lamp drew a pool of moths; beyond it, darkness pressed soft against the house like velvet. The sea’s breath was audible between palms. Mama Tehina shuffled on rubber slippers from kitchen to porch, carrying a bowl heavy enough to bow her wrist. “Taste,” she said, and the bowl was i’a ota, the coconut milk gathered that afternoon, the lime from a neighbor’s tree that he insists is sweeter because it leans into the lagoon wind.

On the table: a plate of fried ature whose eyes stared back like tiny mirrors, a dish of fafa in coconut that had collapsed into the most forgiving green, a jar of miti fafaru in the corner like a sleeping cat. The teenage nephew had made the uru chips, too thick, but we ate them with appreciation; his future was there in the good salt, the clean oil.

There was a story about a net that came back with more crab than fish, a joke about a rooster that crowed at 10 a.m. “He thinks he’s a tourist,” someone said, and the table buckled with laughter. We ate banana po’e that quivered under coconut like a well-behaved child, and the smell of vanilla wandered through like an aunt arriving late and welcomed anyway.

What I remember most, though, was after. Plates stacked, the yard cooling, the lingering smell of lime and fry oil and ti leaf. Mama Tehina sat back, one hand resting on her knee, and said, almost to herself, “Ma’a maitai”—good food. And in that small phrase lived the wealth of this place: not fussed, not plated, not rare, but deeply, daily right.

What to Cook When the Sea Says “Rest”: Rainy-Day Ideas

Some days the ocean is a voice best listened to from land. The swell stacks like a row of mountains. The rain turns roads into glossy snakes. On those days, the kitchen tilts toward comfort:

-

Fish soup from scraps: Heads and bones simmered with ginger, garlic, and lemongrass, skimmed until clear, greens slipped in at the end. The broth tastes like a secret shared by the sea.

-

Corned beef and taro gratin: The colonial pantry is a mixed inheritance, but in many homes a can of corned beef spices taro or cassava into something warming. Baked under coconut milk, it delivers a texture somewhere between cottage pie and Sunday memory.

-

Stir-fried chao men: Noodles with bok choy, sliced fish cake, and slivers of leftover grilled fish, finished with soy and a lick of sesame oil.

-

Sweet breadfruit mash: Uru boiled until tender, mashed with coconut cream and a spoon of sugar, eaten hot with a drizzle of vanilla. Rain sounds better when your spoon steams.

Rain is a pause button, a chance to fix a net, to sew a tear in a pareu, to teach a seven-year-old how to squeeze coconut through cloth until the milk runs like silk.

For the Culinary Traveler: How to Taste Like a Local

If you come to Tahiti seeking flavor, come respectfully and come hungry. A few tips from tables that matter:

- Learn to say “Ia ora na” and “Māuruuru”—hello, thank you. Gratitude is the first seasoning.

- Market smart: Go to Papeete Market at dawn for the smell of wet floor, crushed ice, and perfumed mango; buy what looks alive with color.

- Taste the raw and the fermented: Order i’a ota at a roulotte, and say yes to a family’s offer of fafaru if it’s offered—this is a gift of trust, not a dare.

- Watch a coconut grated: The soft rasp against shell is a lullaby; the milk is a revelation. If you can press it yourself, do. Your hands will feel corrected forever.

- Seek Sunday: If you’re invited to an ahima’a, arrive early with fruit, work if they let you, eat with thanks, and sit after. The post-meal hour is where the best stories are told.

Taste is geography you can carry home. In Tahiti, it’s mapped in lime and coconut, in smoke and stone, in the clean heart of fish that saw the ocean bright this morning. A fisher family’s meals are a reading of that map, line by delicious line.

When the boat returns at dusk, the lagoon pink as a shell’s inside, you’ll find the day’s last chores easy to read: a boy swishes a bucket through water to rinse sand from a shell; someone salts stems of watercress; a grandmother climbs the porch steps with a leaf-wrapped parcel that smells of garlic and earth. In the kitchen, the kettle clicks off; in the yard, a breadfruit dims to embers. Above it all, the sea breathes—an ancient metronome keeping time for meals that have fed this island since long before recipes had names. And in that steady breath, each plate carries the same message: we eat what we love, we love where we are, and the lagoon gives itself back, bright as ever, tomorrow.