Braising Greens Without Bitterness in Southern Dishes

41 min read Master tender, flavorful Southern greens—without harsh bitterness—using smart braising, balanced seasoning, and traditional potlikker for soulful sides that honor heritage with modern finesse. October 20, 2025 07:03

The steam off a pot of greens smells like home: grassy and deep, edged with smoke and vinegar, the kind of aroma that creeps under door jambs and into the neighbors’ good sense. On winter Sundays in my grandmother’s kitchen in eastern North Carolina, the windows fogged while a pot the size of a short story simmered on the back burner. Collards as big as baby blankets were stacked on the counter, grit hissed away under the tap, and a pepper-vinegar bottle—reused and refilled for years—waited beside the stove like a church usher with perfect posture. The potlikker, that mineral-rich broth tinted green-brown, was what everyone really fought over. Cornbread wedges were quartered specifically for sopping duties, and if you were polite you got two swipes before someone cleared their throat and aimed a spoon your way.

We talk a lot about soul and memory when it comes to Southern greens, but there’s a craft underneath the nostalgia: managing bitterness. A good pot of braised greens is not meek; it keeps its backbone and bite, but the bitterness is harnessed—rounded by fat, brightened by vinegar, sweetened by time and onion, and tethered to a savory base that tastes like the land itself. If you’ve ever wondered why your greens lean harsh or muddy, or how to achieve that “Saturday supper at Aunt Lila’s” tenderness, this is your map to braising greens without bitterness in Southern dishes.

The Bitterness Question, Answered by Season and Science

Bitterness is not the enemy; it’s the truth of the plant. In brassicas—collards, mustard, turnips, kale—the bitter edge comes from glucosinolates, sulfurous compounds that can read as sharp or metallic when mishandled. The trick is to transform bitterness from a shout into a harmony.

Timing matters. After the first frost, leaves sweeten. My uncle in Greene County used to call it “the kiss,” as in, “Those collards got kissed last night.” Cold slows metabolism and nudges the plant to produce sugars, which is why market greens in January can taste gentler than the same bunch in October.

Picking variety matters too. Mature collards (Georgia Southern, Morris Heading) are sturdier, less peppery than mustard, and more forgiving during a long braise. Mustard greens (Southern Giant Curled, Florida Broadleaf) are high on perfume—horseradish-y, nose-tingling—but they turn acrid if boiled to oblivion. Turnip greens offer a mild radish zip, especially when young, and kale sits between, with Tuscan (lacinato) kale being softer and less bitter than curly kale.

The kitchen chemistry: heat, salt, fat, and acid all interact with how your tongue perceives bitterness. Cooking breaks down cell walls and disperses those sulfur compounds; salt dampens bitter receptors; fats carry flavor and soften astringency; acids (vinegar, lemon) shift the balance, making bitterness feel purposeful. Umami helps too—the savory depth you get from smoked meats, mushrooms, or anchored stocks makes your brain file bitterness as complexity rather than flaw.

Choosing and Prepping Greens Like a Local at the Market

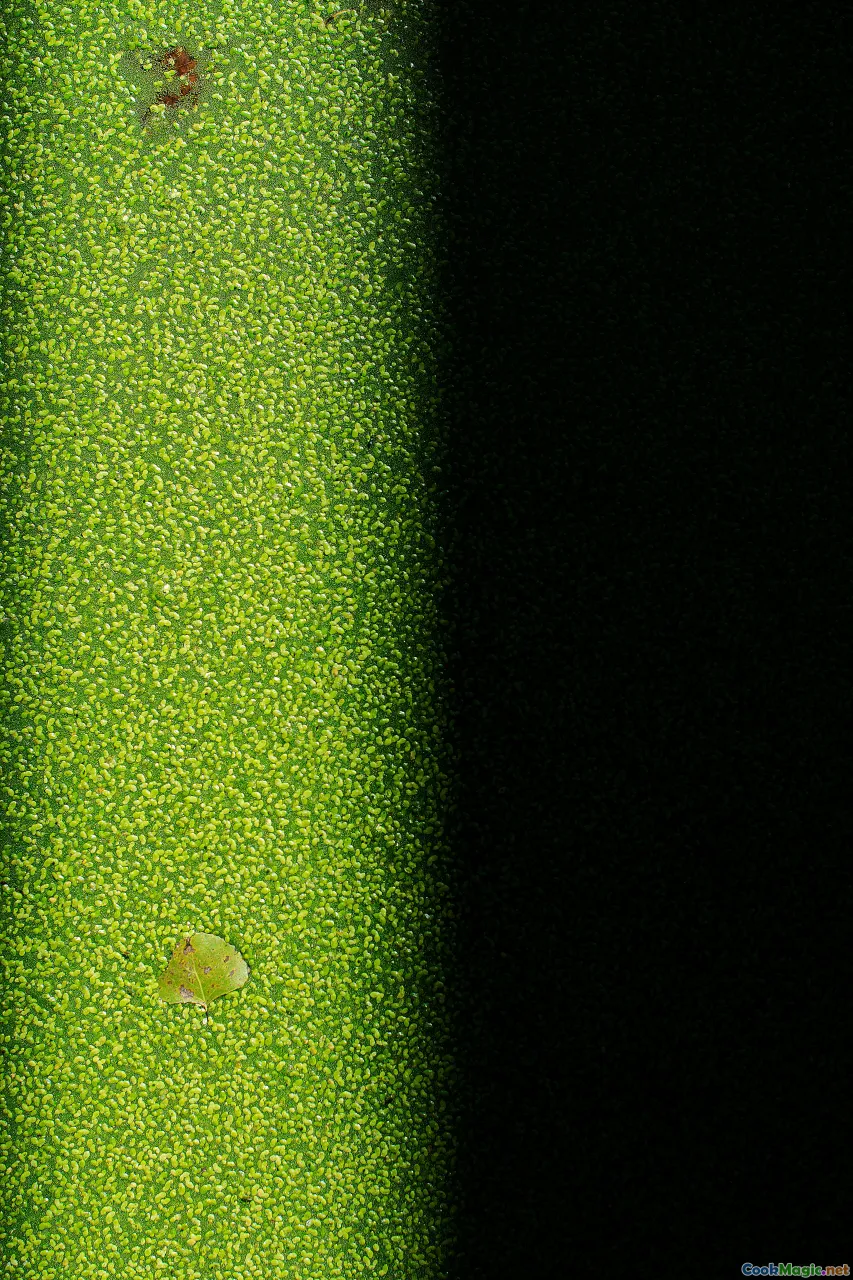

Walk a Southern farmers’ market in winter and you’ll notice the collard stacks: wide ribbons of blue-green folded like fabric bolts. Feel for crisp stems and firm leaves without yellowing or slime. If the leaves are as big as a hubcap and leathery, you’ll need extra time in the pot. If you can find smaller “tender” leaves (often labeled baby collards), you’ll need less.

- Collards: Look for sturdy, matte leaves with thick ribs. The aroma should be fresh, like cut grass.

- Mustard: Curled edges, crinkly and aromatic—give the bunch a sniff. It should smell like pepper and morning.

- Turnip greens: Smaller leaves with delicate stems. Often sold attached to the root—a bonus.

- Kale: Tuscan (lacinato) has long, slate-blue leaves and is less bitter; curly kale is brighter green and more robust.

Wash thoroughly. Grit is the enemy of pleasure, and more than one Southern cook has lost a dinner guest’s trust by skimping on rinsing. Fill a sink or big tub with cold water, dunk the leaves, swish, lift, and drain. Repeat until you see no sand at the bottom—usually three changes, sometimes four.

Destem according to type. Collard ribs are thick; strip the leaves by running a knife along either side of the rib. Save ribs for stocks or chop them fine if you like a little snap. Mustard and turnip stems are more tender; I keep many of them for texture. Kale stems vary; lacinato stems are fine when young, tough when mature.

Cut to size. I prefer a wide ribbon—stack leaves and roll into a big cigar, then slice into 1½-inch strips. Big pieces cook better, hold their personality, and feel more Southern to me. Chiffonade too fine and you invite mush. Keep the leaves slightly wet when they hit the pot; that moisture helps wilt without scorching.

Building Flavor: Smoke, Sweetness, and a Good Backbone

That godly base you taste in the best greens is not an accident. It’s an architecture.

- Aromatics: Onion is nonnegotiable. Dice a yellow onion and let it sweat low and slow in rendered fat until translucent and sweet, about 10 to 12 minutes. One or two smashed garlic cloves deepen the foundation without making your greens taste like spaghetti night. Some cooks add a little celery or bell pepper (a nod to the Louisiana trinity) for roundness, but traditional Carolina collards are onion-led.

- Fat: Pork fat is classic—bacon drippings, salt pork, side meat, or a smoked ham hock. If pork isn’t in your kitchen, smoked turkey wings or necks work beautifully; they lend clean smoke. For vegetarian pots, olive oil plus a knob of butter and a teaspoon or two of smoked paprika will give a whisper of the pit. A spoon of peanut oil adds a roasted note—common in the Deep South.

- Umami boosters: A chunk of country ham, a modest dash of fish sauce (yes, fish sauce—a quarter teaspoon, don’t tell Uncle Ray), or a teaspoon of white miso stirred in at the end. Dried mushrooms or mushroom powder also deepen flavor without stealing attention.

- Salt early, finish with acid: Salt draws out vegetable waters and seasons the potlikker. Final acidity—cider vinegar, pepper vinegar, or even a squeeze of lemon—comes last to protect color and keep the greens supple.

When you inhale your kitchen mid-cook and it smells like a campfire exhaled into a garden, you’re on the right track.

Master Method: Bitterness-Tamed Southern Braised Greens

Here’s the basic blueprint I teach culinary students and impatient cousins. It keeps the greens bright, the potlikker rich, and the bitterness in a pleasant, grown-up register.

Serves 6–8

Ingredients:

- 2½ to 3 pounds mixed greens, prepped as above (collards heavy, with a handful of mustard or turnip for perfume)

- 2 tablespoons bacon fat or olive oil (plus 1 tablespoon butter if vegetarian)

- 1 medium yellow onion, diced

- 2 cloves garlic, smashed

- 1 smoked ham hock, 4 ounces diced bacon, or 1 smoked turkey wing (substitute: 1 teaspoon smoked paprika + 1 teaspoon mushroom powder)

- 1 teaspoon kosher salt to start, plus more to taste

- ½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

- ¼ to ½ teaspoon red pepper flakes (optional)

- 4 cups low-sodium chicken stock or water (filter if your tap water is hard)

- 1 bay leaf

- 1 teaspoon sugar or sorghum syrup (optional but effective)

- 1 to 2 tablespoons apple cider vinegar or pepper vinegar, to finish

Method:

- Render and soften: Heat the fat in a heavy pot (enameled cast iron works like a faithful friend). Add onion with a pinch of salt. Cook over medium-low until glossy and sweet, 10–12 minutes. Add garlic for the last minute. If using diced bacon, render it with the onion; if using a ham hock or turkey wing, nestle it in now to bloom its aroma.

- Bloom the spice: Add black pepper and red pepper flakes, if using, and stir for 30 seconds. This wakes the pepper oils and perfumes the fat.

- Wilt in stages: Add a third of the greens and toss to coat. When they slump, add the next third, then the last. This staggered approach keeps heat consistent and prevents steaming into blandness.

- Season and moisten: Sprinkle the teaspoon of salt and the sugar or sorghum. Pour in the stock or water to come halfway up the greens. You’re braising, not boiling; you want leaves poking above the liquid, breathing as they cook. Tuck in the bay leaf.

- Lid and low: Cover, reduce to a simmer, and cook gently. Collards demand 45–60 minutes to go from crepe-paper to silky; mustard and turnip greens will be pleasant in 20–30. Taste every 15 minutes—be nosy. If your greens include mustard, you may want to lift the lid for the last 10 minutes to let sharper notes drift off as steam.

- Finish with bright: Remove the lid and meat. If using hock or wing, pull the tender bits, shred, and stir back in. Turn off the heat and add vinegar—start with a tablespoon, then taste and adjust. Your mouth should light up, not pucker. Correct salt.

- Rest and serve: Let the pot sit 10 minutes. Greens relax. Serve in a bowl so each portion comes with potlikker. Put pepper vinegar on the table. Place cornbread within moral reach.

Notes on managing bitterness during the cook:

- Sugar isn’t cheating. A teaspoon won’t make the pot sweet; it rounds edges the way a thumb smooths a splinter.

- Don’t add baking soda. Yes, it keeps greens very green by nudging pH alkaline, but it also can make leaves mushy and degrade vitamins, and it shifts flavor toward soap. If color is concern, cook gently, covered, and finish quickly with acid.

- Filtered water: Hard water can make greens taste sharper and cook tougher. If your kettle leaves mineral chalk, use filtered water.

A Tale of Two Kitchens: Atlanta’s Busy Bee and Mama Lou’s Trailer

I learned two lessons about greens in two very different rooms. The first was at Busy Bee Cafe in Atlanta, where the collards come spooned beside hot fried chicken so crisp it shatters like sugar glass. The greens there are balanced—smoky from a discreet ham hock and sharpened with vinegar that hits the back palate, not the tongue tip. The potlikker is glossy and clean, which tells me they skim the fat and keep the braise moist, not drowning.

The second lesson came in a tin-roof trailer near Snow Hill, North Carolina, where Mama Lou (no relation, just a title she’d earned) simmered turnip greens with diced fatback and a whole dried pepper she’d grown on her porch. She swore by adding a teaspoon of sorghum from a jar her cousin shipped each fall. “Take the edge off, leave the story,” she said. Her greens were a little wilder than Busy Bee’s, but in a way that tasted like front porches and Sunday afternoon radio. The takeaway? There isn’t one right way—just a handful of principles that translate across kitchens and steel wheels.

Collards vs. Mustard vs. Turnips vs. Kale: Choosing Your Choir

Think of greens like voices in a choir. You’re casting for the flavor you want.

- Collards: The baritones. Big, steady, mineral-rich, slightly sweet when kissed by frost. They love long cooking and smoke. If you’re feeding skeptics, start here. They rarely go acrid unless abandoned at a boil.

- Mustard: The sopranos. High, bright, nasal in the best way. They can be peppery as a sneeze. Their personality can read bitter if you force them to collard-time. Treat mustard like a cameo: add a handful to collards or cook them on their own for 20–25 minutes with olive oil, onion, and a good dose of vinegar at the end.

- Turnip greens: The altos. Rounder, softer pepper, a little nuttiness. Pair them with the sliced turnip roots to echo their sweetness. They thrive with a pinch of sugar and a generous splash of cider vinegar.

- Kale: The tenors. Lacinato brings depth and a slightly sweet finish; curly kale is bolder, with more chew. Kale loves garlic and olive oil and can go either Southern or Italian in mood. For a Deep South read, keep the smoke and finish with pepper vinegar.

Blending works. My favorite pot is 70% collards, 20% turnip greens, 10% mustard. The mustard perfumes the air; the collards anchor the pot; the turnip greens offer a friendly handshake to anyone nervous about bitterness.

How Bitterness Softens: An Analysis of Time, Heat, and pH

Let’s get precise. Glucosinolates convert to isothiocyanates (think mustard oil) when plant cells rupture. That’s why chopping and rough handling make mustardy aromas bloom. Heat dissolves and disperses these compounds into the cooking liquid; salt buffers your perception; acids compete on your taste buds and give a sense of brightness that tricks the brain into tasting “balance” rather than “bitter.”

- Time: Bitterness declines with gentle time. The key is gentle—rolling boils can concentrate harshness, shake loose chlorophyll, and pound leaves into rag. A low simmer encourages tenderization without leaching everything good into the liquid.

- pH: Acid at the end aids flavor; acid early can dull green color and firm pectin, which is actually useful in keeping leaves from turning to paste. I prefer to wait until the end for color and aromatics, but a teaspoon of vinegar midway can help particularly exuberant mustard greens behave.

- Fat: Lipids carry volatile aroma compounds—smoky phenols, roasted onions—straight to your nose. They also physically coat the tongue, muting astringency.

- Salt: Beyond taste, sodium ions really do reduce your perception of bitterness by altering the responsiveness of taste receptors. Salt early, adjust late.

The Pepper Vinegar That Fixes Everything

Every table I love from the Carolinas to the Delta wears a pepper vinegar bottle like jewelry. Good pepper vinegar brightens a pot like a porch light at dusk.

Quick Pepper Vinegar:

- Pack a clean 8-ounce bottle or jar with whole small hot peppers (bird’s eye, tabasco, Thai, or small green cayennes). Pierce each pepper once with a needle for better infusion.

- Heat ¾ cup apple cider vinegar with ¼ cup white vinegar, 1 teaspoon sugar, and ½ teaspoon kosher salt until just steaming. Pour over peppers, cool, cap, and let sit at least 3 days (2 weeks is better). Keep in the pantry; top off with vinegar as you use it.

This condiment isn’t just heat; it’s a shot of acid that rewires bitter into lively. At Busy Bee, the pepper vinegar is tart and fragrant without vinegary aggression; in Lowcountry homes you might taste a mellowed malt vinegar version with Scotch bonnets, and in Mississippi Delta kitchens I’ve met pepper vinegar deepened with a strip of lemon peel.

Vegetarian and Non-Pork Paths to Deep Flavor

Plenty of Southern churches throw potlucks where no pork crosses the threshold, and still the greens shine. Smoke and umami are flavors, not ingredients.

- Smoked paprika + mushroom: Two teaspoons of smoked paprika plus a teaspoon of mushroom powder mimic the ghost of the smokehouse. Sauté a few chopped cremini mushrooms with the onion for extra savor.

- Miso: Stir a teaspoon of white miso into the finished potlikker off heat. It dissolves like butter and amplifies savory tones without soy dominance.

- Kombu: Slip a 2-inch piece of kombu into the pot during the simmer for glutamates; remove before finishing. It’s a quiet helper.

- Olive oil + butter: The classic duo gives sheen and a soft mouthfeel. Finish with more butter if you want that glossy restaurant look.

With these tools, you don’t need bacon to tame bitterness—you need intention.

Instant Pot and Slow Cooker: Modern Timelines, Same Soul

- Instant Pot: Sauté onion and garlic on Sauté mode with fat. Add greens, 1 cup stock, salt, pepper, and your smoke/umami of choice. Lock and cook on High Pressure 12 minutes for collards, 8 for kale, 6 for mustard/turnip greens blends. Quick release, taste, and finish with vinegar. Pressure cooking can trap sharper aromas, so be generous with acid at the end and, if needed, simmer uncovered for 5 minutes to let brash notes blow off.

- Slow cooker: Layer aromatics and fat on the bottom, pile greens on top, add 2 to 3 cups stock, salt, and bay leaf. Cook on Low 6 to 7 hours or High 3 to 4. Slow cookers can waterlog greens; keep liquid modest and prop the lid askew for the last 30 minutes to reduce. Finish with vinegar.

Either way, the rule remains: low-sodium stock, careful salt, acid at the end, and taste as you go.

Blanching, Myths, and the Case for Restraint

You’ll hear two schools preaching from different pulpits:

- The blanchers: A quick 1–2 minute plunge in salted boiling water, then drain, then braise. This can tame especially assertive mustard greens and wash away some bitterness. It does mean you’ll lose certain soluble vitamins and a bit of that hard-won garden flavor.

- The no-blanch traditionalists: Straight to the pot after a good sweat of onions and fat. This preserves potlikker character and concentrates the greens’ story.

I blanch only when the greens taste fiercely sharp raw (late-season mustard, bolted turnip greens), or when feeding newcomers with delicate palates. If you blanch, braise in flavored liquid—not plain water—so the greens don’t taste rinsed.

And about that potato trick—dropping a potato in the pot does not magically absorb bitterness. It absorbs salt and some liquid. If your greens are bitter, fix the balance: more acid, a pinch of sugar, a few more minutes of gentle simmer, or a splash of umami (fish sauce, miso). Don’t put your faith in spuds.

Troubleshooting: If Your Greens Still Taste Harsh

- Add acid in stages: Start with 1 tablespoon cider vinegar, taste, then add another teaspoon at a time. Pepper vinegar is even better for aromatics.

- Balance with sweetness: A teaspoon of sugar or sorghum calms the edge. Molasses works but can dominate—use ½ teaspoon.

- Extend the cook gently: Another 10–15 minutes at a low simmer softens compounds without wrecking texture.

- Adjust salt: Under-salted greens can taste more bitter because there’s nothing to lean against. Salt until the potlikker tastes like something you want to sip.

- Skim excess fat: Too much grease muddies flavors and can make bitterness feel heavier. Skim with a spoon or blot with a paper towel at the end.

- Freshen: A handful of chopped scallions or a few torn parsley leaves stirred in off heat can perk up a sleepy pot.

Potlikker: The Broth That Built Democracies and Dinner Tables

Potlikker (or pot liquor) isn’t waste; it’s the point. It’s the vitamin-rich, mineral-heavy, deeply seasoned liquid that floats beneath your greens like a southern aquifer. Folks in my family used to pour it into mugs and sip it with a splash of vinegar, especially when winter colds rolled through. It thickens ever so slightly from the pectin of leaves, and it tastes like health, tradition, and whatever smoke you lent the pot.

History has a way of bubbling up here. In 1931, Louisiana’s Huey Long got into a famous public kerfuffle about potlikker etiquette—whether to dunk cornbread or crumble it into the bowl. Newspapers ran with it like it was foreign policy. The real policy is this: don’t waste potlikker. Save it for cooking beans, boiling rice or grits, simmering black-eyed peas on New Year’s Day, or enriching chicken soup. I boil diced turnips in leftover potlikker, then mash them with butter and black pepper for a genius side that tastes as if it came from a smoke-kissed root cellar.

Condiments, Sides, and the Company Greens Keep

Greens wear companions well:

- Cornbread: Skillet-cast, crackling-edged cornbread in Appalachia; hot water cornbread in the Delta, fried into crisp cakes that shatter and then drink up potlikker like a thirsty field. I like mine with buttermilk in the batter to echo the vinegar on the table.

- Chow-chow: Pickled cabbage relish—sweet, tangy, crunchy—cuts through richness and brightens the plate. In eastern North Carolina, a spoon of chow-chow on collards is as normal as a porch swing.

- Peppers and hot sauce: In Nashville diners you’ll often see Crystal or Texas Pete alongside the pepper vinegar. Hot sauce brings its own acid; use lightly.

- Pairings: Catfish fried in cornmeal, country-style steak, smoked turkey legs, barbecued pork shoulder, meatloaf glossed with tomato. Grains and legumes love greens: grits, Carolina Gold rice, Hoppin’ John, white beans.

- Drinks: Sweet tea is undeniable—the tannin plays with bitterness the way salt plays with sugar. If you’re pouring wine, choose an off-dry Riesling or a high-acid white like Albariño; for beer, a crisp pilsner or Kölsch.

Seasonal Notes and the Garden’s Rhythm

Winter collards after frost are the South’s quiet luxury. In early spring, mustard greens reach peak perfume before bolting. Summer greens can be coarser and more assertive, which means blanching may help. Remember: younger leaves are milder; older leaves hold more mineral depth. If you grow your own, harvest in the cool morning, when leaves are plump with overnight water. If you can, cook the same day—greens collapse sadly in the fridge, losing pep and scent.

Regional varieties deserve their own stanza. In Georgia, “Morris Heading” collards form a loose head with tender inner leaves; in the Carolinas, “Georgia Southern” remains the home cook’s workhorse; in Mississippi’s Delta, cooks often reach for turnip greens with the roots attached, making a whole-plant supper with cornbread. At Charleston markets, you’ll find pepper vinegar bottles with the caps stained from years of splash, and vendors who swear on one brand of cider vinegar like it’s kin.

A Cook’s Routine: Weekend Prep, Weeknight Pleasure

Greens are generous with time. Cook a big pot on Sunday and the leftover flavors marry beautifully by Tuesday. I strain extra potlikker into jars for:

- Cooking grits on Monday morning.

- Steaming rice for Tuesday’s shrimp and sausage skillet.

- Rewarming the greens gently on Wednesday, adding a new splash of vinegar to revive brightness.

If you plan to freeze, undercook by 10 minutes and cool quickly. Freeze with some potlikker so reheating doesn’t dry the leaves. I’ve pulled a quart from the freezer in July and felt a January kitchen bloom in my air-conditioned apartment.

Advanced Moves: Layering Flavors Without Bullying the Greens

- Bay leaf and allspice: A single bay leaf is standard, but one crushed allspice berry adds a Lowcountry whisper that plays well in pork-forward pots.

- Mustard seed: For mustard greens, bloom a teaspoon of mustard seeds in the fat with the onion; it puns on the plant and adds peppery bloom without bitterness.

- Citrus: A strip of lemon zest simmered with the pot and removed before serving lightens the whole endeavor.

- Heat control: Too hot and you concentrate bitterness; too cool and you risk a swamp. The sweet spot is a burp every second or two—not a riot.

- Skimming: In meat-forward pots, skim froth during the first 15 minutes to keep flavors clean.

New Year’s Day Tradition, Old Feelings

On New Year’s Day, I count money with my mouth—collards for cash, black-eyed peas for luck, and cornbread for gold. My cousin Evie insists the greens must be cut into long ribbons for long money. As we eat, someone always retells the story of Aunt Odette who swore that doubling the vinegar doubled your bounty. We all laugh, then sneak more pepper vinegar anyway.

That meal is a delicious superstition wrapped around a practical truth: in winter, when the fields are bare of tomatoes and okra and the air is sharp, greens are the sturdy constant. They remind us that the earth keeps giving even when we think she’s done.

A Plate in Savannah, A Field in Pittsboro, A Lesson Everywhere

At Mrs. Wilkes Dining Room in Savannah, greens arrive family-style in big bowls that make strangers pass kindness along with a serving spoon. The collards there are tender enough to slump, with a potlikker I could drink like tea. If you look closely, you’ll see the sheen—light, not greasy—proof of restraint and skimming.

Outside Pittsboro, North Carolina, I once walked a patch of collards after a night of frost. The leaves had gone a glossy hunter green, edges slightly brittle. The farmer rolled a leaf into a cigar, sliced off a strip with his pocketknife, and handed it to me. Raw, it was sweet as a frozen pea and bitter in the way coffee is: present, thoughtful. “Cook it right,” he said, “and the bitter stays but acts nice.” I think about that every time I reach for the vinegar bottle.

In Case You Want Exact Ratios: A Chef’s Cheat Sheet

For 1 pound of hearty greens (collards/kale):

- Fat: 1 tablespoon

- Onion: ½ medium, diced (about ¾ cup)

- Garlic: 1 clove

- Liquid: 1 to 1½ cups stock or water

- Salt: ½ teaspoon to start

- Sugar: ¼ teaspoon

- Acid: 1 to 2 teaspoons at the end

- Smoke: 2 ounces smoked meat or ½ teaspoon smoked paprika

For 1 pound of tender greens (mustard/turnip):

- Fat: 1 tablespoon

- Onion: ½ small, diced (½ cup)

- Garlic: 1 clove

- Liquid: ¾ cup

- Salt: ½ teaspoon to start

- Sugar: ¼ teaspoon

- Acid: 2 to 3 teaspoons

- Smoke: Go light; a small ham hock or ¼ teaspoon smoked paprika

These aren’t laws, but they’ll get you to a place where bitterness behaves, and flavor sings.

Why This Matters: Greens as Memory, Greens as Craft

Cooking greens the Southern way, without bitterness, is not about eliminating what a plant is. It’s about courtship—wooing the leaf into tenderness, offering it companions that make it shine, and honoring a lineage of resourceful cooks who turned hard leaves into comfort with little more than time, smoke, and vinegar.

When the pot goes quiet and you lift the lid, you’ll see the color—deep, not garish—and the leaves will slump like someone slipping off their shoes after church. The potlikker will smell faintly of wood smoke and earth after rain. Pepper vinegar will ping your nose. You’ll tear a corner of cornbread and remember someone who taught you to cook even if you never met them. Bitterness won’t be gone; it will be transformed, like grief into story, like memory into muscle.

And if a neighbor wanders over, nose first, to ask what’s on the stove, ladle them a bowl. Hand them the pepper vinegar bottle without making a fuss. Nobody leaves hungry when there’s a pot of greens on, and nobody leaves without a little of the South clinging to their breath—in the best way—smoke, garden, and a bright, happy tang.